The jury has reached a verdict. Derek Chauvin is guilty for the murder of George Floyd.

On May 25, 2020, the police officer kept his knee pressed into the 36-year-old African-American man’s neck for 9 minutes and 29 seconds.

Videos taken by the police’s body cameras and bystanders, from Minneapolis, have spread around the world. They’ve made their way into every home, onto every cell phone. Floyd, with his face pressed to the asphalt, even calls his mother to the rescue. Until he is out of breath. Until he doesn’t answer anymore.

Something changed that day. In an increasingly polarized America, the murder marked the moment when everyone had to come to terms with reality and decide which side they were on. Just before the verdict, we interviewed Tyler Sit, reverend of ‘The New City Church,’ a Methodist church seven blocks from the street where George Floyd’s murder took place.

Black Lives Matter

“Tensions are high” Tyler Sit tells us, just hours before the verdict is pronounced. “Minneapolis—and by extension, the country—is facing a critical juncture: will we take the brutalization of Black bodies seriously or not? If so, then we must risk reimagining public safety and investing our resources in community development on a broad scale. If not, I imagine there will be many more George Floyd- like murders (and uprisings) until we learn our lesson.”

Tyler’s memory of the day of the murder is indelible. “I remember it like it was yesterday. The people of New City sprung into action all over the city: going to protests, holding vigils, gathering their neighborhood together, coordinating food distribution, and more. We hosted online vigils that had tens of thousands of views from all across the country.”

Tyler also tells us how the murder raised a new awareness within his community. “The story of the uprising that no one tells is how it taught the people of Minneapolis to look out for each other, to see that ‘if I am safe but my neighbor is not safe, then I am not safe.’ We have established networks of resource sharing and community care that persisted even after the fires on Lake Street went out.”

The New Church

In 2017, Tyler founded “The New City Church.” The church is part of the United Methodist Church (UMC), a Protestant denomination based in the United States. With at least 12 million members, the UMC is the largest denomination within the broader Methodist movement, which is followed by about 80 million people worldwide.

But “The New City Church” seems to look beyond narrow religious rules. The name comes from a passage in Revelation that describes a “new city” where all tribes are welcomed, where there is no more violence and where the whole earth is renewed. “In many ways, New City represents the type of community that we hope our whole city can have in the future!” says Tyler. The New City brings together members with all kinds of racial/ethnic identities, socioeconomic statuses, gender and sexual identities, intellectual and physical abilities, immigration statuses, and religious beliefs (some members don’t even identify as Christians).

Centering Marginalized Voices

In his book, released in early April and titled “Staying Awake – The Gospel for Changemakers,” Tyler lists 9 things Christians should do to “stay awake” in the face of the world’s suffering and in the name of justice. One of these is centering marginalized voices.

He explains how, “It simply means allowing the experience of people who are historically and currently oppressed by society to direct the conversation. My church does our best to center marginalized voices because it is on the margins, we believe, that God shows up. It’s not just about ‘charity’ or helping the ‘less-thans’; it’s saying that if we want to follow God we have to go to where God is moving—the margins of society. In Minneapolis, both during the George Floyd uprising and what is happening with Daunte Wright, I am seeing this played out in real time. In these instances, centering marginalized voices means listening to the people who were brutalized by the police— full stop. While conversations about looting are of course also important to the community, if we do not start and end the conversation with asking, ‘why did these people die and how do we change so it won’t happen again?’ we are only distracting ourselves from the main issue at hand.”

Gentrification

It’s not just police brutality towards African-Americans that is a concern for the Minneapolis community. Tyler tells us that many times he has spoken with city residents who consider themselves too poor to afford to live in a green and safe neighborhood. A recent study by the University of Minnesota shows significant evidence of gentrification in the city of Minneapolis.

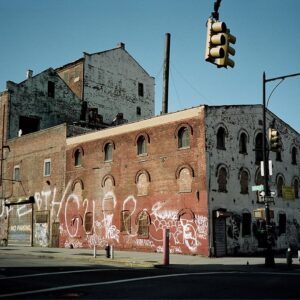

The term gentrification refers to the transformation of a low income neighborhood into a premium housing area. The effect of this urban improvement is that house prices go up, renters can no longer afford them, they are evicted, and replaced by those who, instead, can afford a higher price. Many consider Brooklyn to be the most striking example of gentrification in New York City. Over the years, the borough has been transformed from a neighborhood historically inhabited by Poles, Dominicans, Puerto Ricans and Hasidic Jews, to what is now internationally known as the most gentrified place in New York.

Tyler explains the problem this way, “A low-income community of color in an urban area gets ‘developed’ by outsiders, mostly white developers (think luxury condos and artisanal cheese shops), then the cost of living goes up and the original community is displaced out of the neighborhood. The problem, of course, is not economic development. New businesses, trees lining the sidewalk, and greater public transit access can all be very good things! Who doesn’t like some good artisanal cheese? Rather, the key word here is ‘displacement.’ After all, economic development is largely possible because residents have worked – sometimes for generations – in the neighborhood before it was ‘cool,’ and those residents should be able to stay there once developers benefit from their hard work. Affordable housing, gradual economic growth, and things like land trusts are all part of the solution to counteract gentrification.”

Asian Hate

Discrimination also affects the Asian community in America. In the last year, incidents of racism against people of Asian origin (or appearance) have increased across the country. Stop AAPI Hate, the reporting center created by the Asian American Studies Department at San Francisco State University, recorded 3,795 incidents of hate, violence, harassment, discrimination and bullying against Asian Americans in 2020. The report also shows 42 incidents in Minnesota. And that’s just the number of reported incidents.

Tyler is second-generation Chinese-American and tells us that while he hasn’t been directly assaulted, he has heard many stories of people being attacked. “When I walk on the street, I watch my back. Ultimately, though, I know that if this intimidation stops me from living my everyday life, then racism has won, so I try to keep going the best I can.”

He also finds the strength to move forward by looking at the example of his parents, “My mom, who is white, and my Dad, who is Chinese, proved to me that deep relationship is possible across cultures. My family is living proof!”

Gay Marriage

Other marginalized voices, especially in religious communities, are those of LGBTQ+ people. Tyler’s community is primarily led by young gay people of color. Tyler himself is openly gay.

The United Methodist Church’s “Book of Discipline”, which contains the laws and rules for Methodist believers, states that “sexual relations are affirmed only with the covenant of monogamous heterosexual marriage.”

But Tyler’s New City Church openly opposes the decisions made on marriage and LGBTQ+ ordination by the United Methodist Church, opening up the possibility – increasingly real – of yet another schism.

“New City Church supports gay marriage,” Tyler says. “We decided to do this as a community—not just because I am an openly gay person myself! The decision came from a groundswell of LGBTQ+ people and their friends, parents, and relatives all agreeing God calls us to create an inclusive church. Of course, not all United Methodist churches are of one mind on this matter, and it appears that a denominational schism is all but inevitable. I don’t lose sleep over this—much of the New Testament was written in the midst of various community schisms (over circumcision, over whether to accept Gentiles, over ritual food eating, and more). Even amidst all of that, the Spirit of God continued to move people toward community, healing, and justice.”