October 4 is the Feast Day of St. Francis of Assisi, the patron saint of Italy, ecology, animals, and tapestry makers. This year celebrations were particularly festive. Pope Francis went to Assisi on his first official trip outside Rome since the lockdown in March, to sign his third encyclical, “Fratelli Tutti” on his namesake’s tomb.

Originally written in Spanish, the Pope’s native tongue, and in part before the Covid-19 crisis, after its publication the text was immediately translated into Arabic, French, English, Italian, Polish, Portuguese, German and Latin. Its eight chapters and 287 points present Pope Francis’s vision for a post-Covid-19 world: the universal and urgent need for increased fraternity, dialogue and solidarity, all for the common good.

Here the Pontiff explains why market capitalism failed during the pandemic.

He emphasizes that the world can no longer afford to continue its globalization of economic and social indifference or to sustain closed-minded nationalism. In order to build a just and peaceful world, he writes, we must create jobs, thereby abolishing at least some of the injustices of the present global economy.

We must also eliminate the nuclear arms race (point 262), traditional warfare because “its risks will probably always be greater than its supposed benefits. In view of this, it is very difficult nowadays to invoke the rational criteria elaborated in earlier centuries to speak of the possibility of a ‘just war’. Never again war!” (points 256-61), as well as capital punishment (points 263-70).

In addition, we must strengthen the United Nations, speak out against racism and learn to organize fairly the enormous wave of immigration from the World’s south to its north. Although not surprisingly, Pope Francis also advocates tolerance for these desperate people, forced by wars, famine, or religious discrimination to leave their homelands, as well as respect for the believers of other religions, especially Islam, citing five times his 2019 appeal with the Grand Imam of Egypt Al-Azhar, the revered 1,000-year-old seat of Sunni Islam.

Of course, again not surprisingly, many—politicians, clergy, and conservatives- condemned his views on these last two issues. Yet it should not be overlooked that in 1219 St. Francis, in support of inter-religious tolerance, had also traveled to the Holy Land to meet with the Sultan Melek-al-Kamal.

Like his second encyclical, “Laudato Si’”, (“Praise Be to You”, subtitled “On Care for Our Common Home”), officially published on June 18, 2015, “All Brothers” was inspired by St. Francis. “Laudato Si’”, a critique of consumerism, irresponsible “development”, environmental degradation and global warming, are the opening words of each verse of the saint’s Canticle of the Creatures, written in 1224.

Instead “All Brothers”, its title unfairly criticized by some as deliberately excluding women, are the opening words of St. Francis’s “Admonitions”, 28 short and deeply spiritual exhortations written by the saint throughout his lifetime to encourage and guide his Franciscan brothers in their vocation. The title’s short-sighted critics should be reminded that Bergoglio’s first words as pope from St. Peter’s balcony were “Fratelli e Sorelle, Buona sera.” (“Brothers and Sisters, good evening”.)

Two other recent events are also connected to St. Francis: the publication by Mondadori on September 29th of “La tunica e la tonaca: due vite straordinarie, due messaggi indelebili, by Father Enzo Fortunato, which juxtaposes the lives of Jesus and of his disciple St. Francis.

Fortunato points out that Jesus was denuded and ridiculed by his Roman soldier jailers who cast lots for his clothes, whereas St. Francis, the son of a wealthy cloth merchant, undressed and exchanged his expensive garments for a beggar’s grimy garb. So, while in the first instance it was St. Francis’s cassock that had first belonged to a castaway, in the second, Jesus himself was the castaway.

Perhaps unknowingly in advance, the book’s message is similar to “Tutti Fratelli”.

For both, Pope Francis and Father Enzo, St. Francis’s torn cassock symbolizes the sick and disoriented state of our world today. That just as Santa Chiara had mended St. Francis’s cassock, we must repair the world. The pandemic has clearly given us this opportunity.

We must put aside our personal differences through dialogue, improve international relations, and diminish economic inequality. With the lives of Jesus and St. Francis as our compass, our goal must be to create a just and peaceful world. Spokesperson for the Franciscan Friary in Assisi, Father Enzo is the author of several other books about St. Francis, all available in Italian only on the internet.

As for St. Francis’s cassock, four Franciscan churches in central Italy claim they each have a cassock of St. Francis. One is in Assisi’s Basilica; a second is in the Sanctuary of La Verna near Arezzo in Tuscany; a third in the Basilica of the Holy Cross (Santa Croce) in Florence, and the fourth in the Basilica of Cortona, also near Arezzo. Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) tests have shown that the robe in Florence is 100 years too young to have belonged to St. Francis; the other three date to St. Francis’s lifetime.

Thanks to its ever-imaginative and super-active director Eike Schmidt and his staff, there are two new installations at the Uffizi in Florence, one online and one in situ. Since the beginning of lockdown they have added many virtual tours of the museum’s collections to its website. The most recent, released on October 3, is entitled “Il Francesco Fratello Universale-vita e culto del poverello d’Assisi” (Universal Brother Francis-the life and cult of the poor man from Assisi) .

Although I think everyone would agree that Giotto’s frescoes of St. Francis’s life on the walls of Assisi’s Basilica are the most famous and most moving depictions of the saint, the Uffizi’s tour of its 29 artworks dating from 1240 to 1925, includes paintings, etchings, and sculptures of, or with the saint, or of locations important in his life. With the exception of Filippo Lippi, El Greco, and Jusepe de Ribera, however, none are household-name artists.

Also on October 3, after extensive restoration lasting almost 20 years, the Uffizi reopened on its ground floor an area that had been out-of-bounds except with special permission. It is once again on the museum’s touristic itinerary.

When the Renaissance architect, painter, and art historian Giorgio Vasari built the Uffizi in c. 1560, he incorporated this area, which once had been the site of an important 11th-century church, San Pietro in Scheraggio, itself built on the site of a pre-existing church. Vasari reduced the size of the church and incorporated some of the church’s columns in the Uffizi’s walls. One such column has a fresco of St. Francis with his stigmata and wearing his brown cassock. At the column’s base to the left of St. Francis are pictorial traces of the fresco’s lady sponsor.

During the Middle Ages San Pietro in Scheraggio (meaning St. Peter Above the Sewers) was a large building with three naves, a crypt and a cemetery. Besides its religious obligations, it had an important role in the Florentine government’s civic administration of those times. The solemn swearing-in ceremony of the Priori delle Arti, a kind of 6-member city council or guild, took place in the church, as did its subsequent meetings.

It’s documented that Dante served from June 15-August 25, 1300 and took his oath here. The restorers’ installation of a transparent floor in the one nave incorporated by Vasari has made it possible to admire the church’s medieval remains below.

When it comes to New York, “The City That Never Sleeps” also has a parish dedicated to St. Francis Assisi. Located at 135-139 West 31 Street in Manhattan since the 1840s, a block south from Pennsylvania Station and Madison Square Garden, its present neo-Gothic building was completed in 1892. Soon afterwards the friars realized that the neighborhood’s working class population was moving away and had been replaced by a largely transient congregation of Broadway actors, shoppers, commuters, and tourists. To better provide for “the newcomers’” spiritual needs, the friars introduced the “Nightworkers’ Mass”, held at midnight, and later a “Noontime Mass”, becoming the first church in the United States to do so.

Needless to say, the parish’s community service didn’t stop then. In 1930 the friars responded to the Great Depression with a breadline,

a service they still provide, making this parish the oldest one in the United States to have operated a breadline continuously. Beginning in 1980 they also have provided housing in the neighborhood for the chronically mentally ill.

In 2001 the parish priest Father Mychal Judge was also chaplain to the New York City Fire Department. On the morning of September 11th, upon hearing about the terrorist attacks at the World Trade Center, he rushed downtown. While ministering to a victim he was struck by falling debris and killed instantly. He was the World Trade Center’s first official fatality.

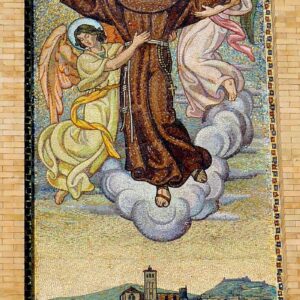

If for no other reason, stop by to admire the “Great Mosaic” of “The Mother of Jesus”, one of the largest in the United States, by the Austrian painter Rudolf Margreiter and Joseph Wild (1925), and other smaller ones of “Jesus”, “The Assumption” and “The Death of St. Joseph” as well as one of “St. Francis” on the church’s façade.