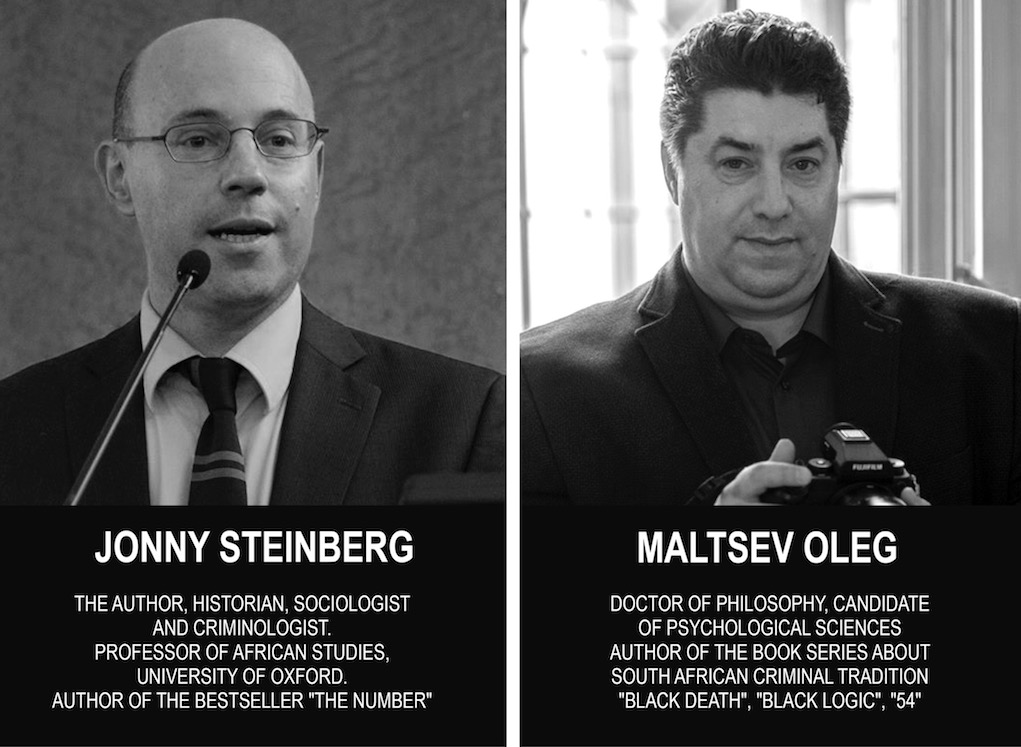

Prof. Jonny Steinberg is a professor of African Studies, University of Oxford and the bestselling author. He has worked as a journalist at a South African national daily newspaper, written scripts for television drama, and has been a consultant to the South African government on criminal justice policy.

Prof. Jonny Steinberg is a professor of African Studies, University of Oxford and the bestselling author. He has worked as a journalist at a South African national daily newspaper, written scripts for television drama, and has been a consultant to the South African government on criminal justice policy.

PhD Oleg Maltsev is a lawyer and researcher of world criminal traditions, the author of more than 15 books in this area with field scientific expeditions conducted around the world. Founder and head of the Research Institute of World Martial Art Traditions and Criminalistic Research of Weapon Handling

Dr. Maltsev: You have already written several serious works on South African Number gangs, which definitely deserve special attention. Are there any other unpublished books or scientific articles?

Dr. Steinberg: No, in this area I have written one book The Number: One Man’s Search for Identity in the Cape Underworld and Prison Gangs and the monograph Nongoloza’s Children.

Dr. Maltsev: What has prompted you to write The Number? It is quite a complex book.

Dr. Steinberg: Well, the idea was triggered before I had started working as an academic at Oxford University. When I was working as a journalist, I went on an assignment for an Italian magazine to Pollsmoor maximum security prison. That was in February 2002. Before that day I had not heard of Number gangs, I had not heard of Nongoloza. My imagination was completely captured by the idea that there was this criminal world, that was organized with a very long history, with its own set of rituals and mythological story about Nongoloza. It was to me a huge revelation, and I wanted to know more.

Dr. Maltsev: Could we say that The Number is a stage of your research of South African criminal subculture or is it already the result of research done prior to writing the book?

Dr. Steinberg: Certainly, we are speaking of results, I did the research in order to write The Number

Dr. Maltsev: The research you have done, was it carried out in the framework of one academic discipline or was it done at the intersection of disciplines?

Dr. Steinberg: I work in the university of Oxford now as an academic, at that time I was a full time writer and I didn’t think of myself in any one particular discipline. I thought that I would draw on whatever was useful no matter what discipline it was in.

Dr. Maltsev: Basically can we perceive this work as the result of a comprehensive and integrated research?

Dr. Steinberg: Yes. If I breakdown the methodology that I have used, we would say it had four directions. The most important one that I’ve used was oral history: talking with people involved in gangs about the history of the gangs. Secondly, I have done a fair amount of archival research. I have examined old court records, old commissions of inquiry as well as the work historians have done, particularly the historian Charles Van Onselen who wrote about Nongoloza. Finally, I have done quite a bit of participant observation which is drawn from sociology, I have spent a lot of time in the prison and a lot of time with former prisoners in their communities.

Dr. Maltsev: When you were working on the book, what kind of task did you set before yourself?

Dr. Steinberg: My goal was to write a popular book rather than an academic book. From the beginning I was paying particular attention to story telling. I guess my first idea was to tell a story about a cell in Pollsmoor prison, the story would be about all the men who lived in that cell, and their stories. But as the project progressed I realized that it would dilute the story and I ended up writing it around the life of one man. That was not my intention at the beginning, I guess that became the idea of the book 6 months since the research.

Dr. Maltsev: I would like to explain why have I have asked this particular question. For me as for a scientist it is important to understand what layers of information are contained in the book, because everytime I read it I find out something new for myself.

Dr. Steinberg: I am interested to hear your opinion, because I haven’t read the book in 14 years after its publication. I am going to be reading it again this summer. I am sure it is going to be a very interesting experience for me as a reader. It will be almost like a book somebody else has written.

Dr. Maltsev: The first thing I can say as a scientist is that this is the hardest book about Number gangs that exists.

Dr. Steinberg: Thank you

Dr. Maltsev: It is very psychological

Dr. Steinberg: Yes

Dr. Maltsev: And since I am a candidate of Psychological Sciences this book is a certain research polygon for me

Dr. Steinberg: Great

Dr. Maltsev: Because there is no other man who has written a book about South African criminal subculture with such a volume of psychology in it. Usually what can be seen is an attempt to analyze Number gangs from the viewpoint of sociology, criminology or history.

Dr. Steinberg: As it was a long time ago, I think I didn’t mean to make it that intensely psychological when I started it. What happened is that I’ve developed warm relationship with the main character of the book – Magadien. I became so intrigued by him as a human being, and as I worked on the book that’s more and more where my energy was drawn. I guess it is one reason why it became such a predominantly psychological book.

Dr. Maltsev: Thats fascinating, because there is no other writer who wrote this kind of a book about gang psychology.

Dr. Steinberg: Thank you

Dr. Maltsev: Everybody else was trying to describe the overall general phenomenon of gangs

Dr. Steinberg: Correct

Dr. Maltsev: In the Johannesburg state archives library I found certain police reports. These documents state the fact that Nongoloza did cooperate with the police, which is contradictory to today’s myth about Nongoloza. What do you think about this fact?

Dr. Steinberg: Yes, that’s absolutely correct. It was a long time ago and I can’t remember the name of the police officer who turns Nongoloza. But yes I talk about the same story in The Number, he did began cooperating with the police. When writing The Number it was interesting to me that, when Nongoloza turned and began working for the police he was about the same age as Magadien, the man I was writing about. I was very struck by the fact that gangs were for young men and I was interested in what happens to men in gangs as they grew older. In a way there was a parallel between Nongoloza all those years ago and Magadien who became my friend. Both of them belonged to Number gangs and in their early 40s they both decided to start working with the authorities against the gang. This phenomenon interested me and I begun searching interdependence between the age and changes of their views.

Dr. Maltsev: Could you please tell me which book was first – The Number or Nongoloza’s Children?

Dr. Steinberg: The Number was prior. The reason I wrote Nongoloza’s Children was the following: while I was writing The Number I was working on it full time and exclusively, and in order to do that I raised money from a NGO and part of the deal, part of getting the grant from them was that I would write a separate academic document for them. The Number was my primary project.

Dr. Maltsev: If you were to write a scientific book about Nongoloza what kind of methodology would you use?

Dr. Steinberg: I guess the discipline in the university that I am most attracted to would be history, and the primary method being oral history. I think this would be the most relevant answer in the given case, even though to be honest I do not prefer to draw boundaries among disciplines. I prefer interdisciplinary research. That’s why I would add sociology and anthropology as well.

Dr. Maltsev: In this regard our approaches to conducting research coincide. It seems to me that this type of book cannot be written in the frameworks of one discipline.

Dr. Steinberg: I agree, completely

Dr. Maltsev: Could you please share what you think in regard to how the european academic world reacts to interdisciplinary research?

Dr. Steinberg: Well, the set where I work here at the Oxford University, African Studies is an interdisciplinary institute. Oxford really values interdisciplinary tradition. I think it is America which is much more concerned about disciplinary boundaries than Europe.

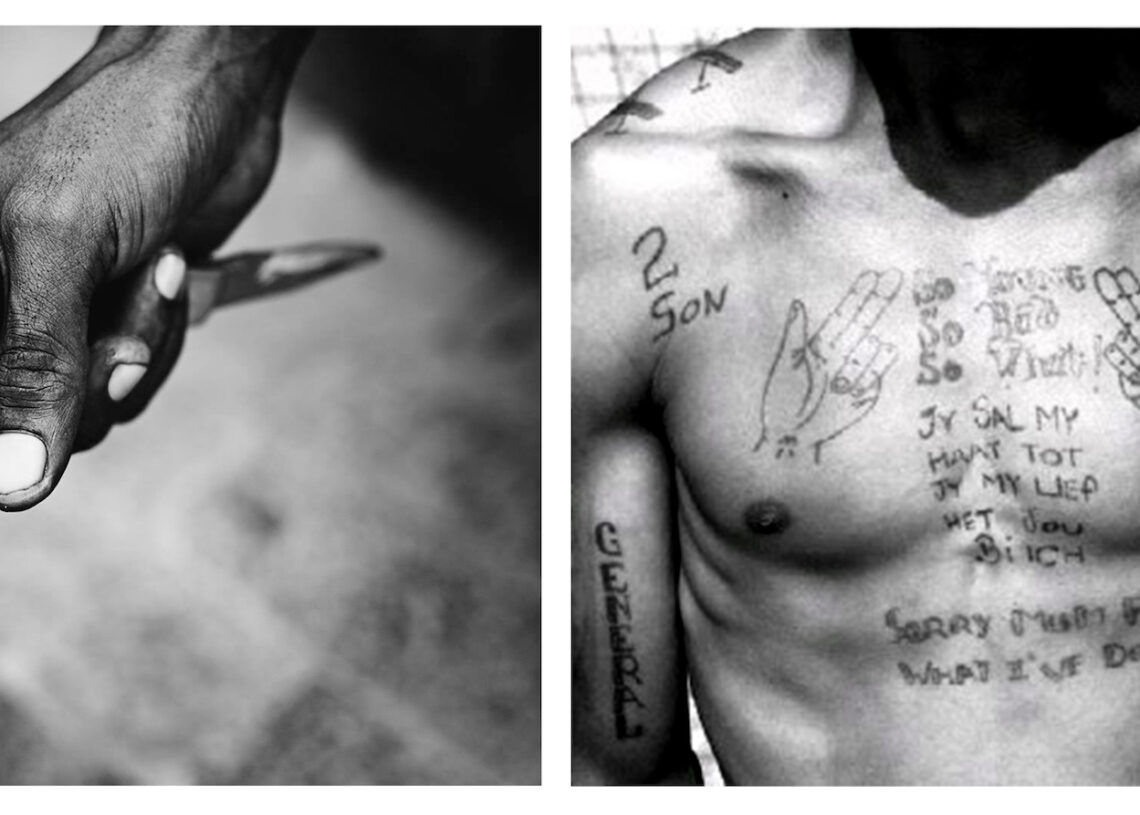

Dr. Maltsev: Thank you very much for clarification. Could you please speak about your view towards the existence of a certain weapon handling system in Cape Town gangs? Is it a myth or does the system really exist?

Dr. Steinberg: That’s such an interesting question, I was already struck by the fact there was a gap between the way people spoke about the gangs and what gangs actually did. These myths and misconceptions go for everything: for the handling of weapons, to the way people speak to each other, to the rules of conduct. There was an idolized sense of what the gang did in people’s heads – and then, the real world. And there was quite a big difference. But what I was most interested in, was the fact that day to day the real world can run without observing gang law, but then at certain moments it suddenly became very important to observe the gang law including how weapons were handled, and those were ritualized moments – when something very important was happening.

Dr. Maltsev: From your point of view as a researcher and scientist, could we really speak about the existence of a system which is taught in the prison and which allows gangsters to kill people with a blade? Or is it a myth?

Dr. Steinberg: Well, I think that the system exists, but sometimes it is obeyed and sometimes it isn’t. I am interested in why it is obeyed at certain times and why not at others. Somebody can bring a knife that is not allowed and they can get away with it for a long time, and then all of a sudden they are in trouble for having the wrong knife. And I am interested in why, why did the rule worked that day and not the other day, what was going on that made the rule legitimate that one day?

Dr. Maltsev: Can we explain this by the level of access to information because there is a certain hierarchy in gangs?

Dr. Steinberg: Certainly the system of the Number gangs requires secrecy and access levels. And yet in the real world that simply isn’t true, because by now so much information about gangs has leaked out. That’s a particular instance when the gap between myth and reality is so strong. The mythological system of the gangs insists that the knowledge is secret and yet it is there to some extent. The gangs exist in a series of contradictions and paradoxes.

Dr. Maltsev: I completely agree with you. I have been looking into Number gangs for about 2 years by now and wrote three books about their subculture and cold weapon handling techniques. I had also asked the same question – if it is such a secret organization, if the system inside is accessible only for insiders, then as a rule nobody should have known about these things?

Dr. Steinberg: That’s right.

Dr. Maltsev: Does it turn out that this is a certain project? We could assume that there is a certain third party which manages what’s going on and stays aside. Somebody has started using the South African criminal subculture at some point for financial purposes. During preparation for the expedition to South Africa there were people, who сonfused my expeditionary corps with usual tourists, who have been proposing us extreme excursions to Pollsmoor prison, meeting with the leaders of 26, 27, 28. It looks ridiculous from one side and very strange from the other side. Frankly speaking, a theatre of absurdity.

Dr. Steinberg: That’s an interesting point. One important thing that happened was that towards the mid or late 1980s the drug trade on the Cape Flats became much bigger business and much more international business. The apartheid period was coming to an end and the South African economy in general opened up to the world economy. That had an extreme effect on gangs because street gangs outside the prison became vehicles through which businesses made money. What many gangsters out in the streets did was that they started bringing fragments of the prison Number gangs onto the streets, ready for the purpose of branding their drugs. Until the mid 1980s the street gangs were very localized, you would have one per neighbourhood. What people selling drugs on a large scale needed were gangs that were regional, people that never met but belonged to the gang. That was an important device to sell drugs on a large scale. Number gangs came out of the prisons and got absorbed into a market, into a capitalist economy.

Dr. Maltsev: I will add more explanation to the reason I have asked this question. Several months ago I was in Calabria with the scientific expeditionary group. As you know there is an organization which is not less infamous than Number gangs. It is extremely hard to find out authentic information about ‘Ndrangheta. Meanwhile so called gangsters in the South Africa are willing to be interviewed, to be filmed for documentaries and they are not reluctant to contact with governmental structures and the press. There is nothing as such in any country. One does not see this in Russian, Spanish, Italian nor in Mexican criminal tradition. Therefore, there is a question which comes up – could it be that it is a modern mechanism of attracting tourists into South Africa, in particular to the Cape Town?

Dr. Steinberg: No, I don’t think it’s tourism. But I do think what happened, when the information started spilling out, when the gangs opened up, it became a very attractive subject for documentary makers, journalists and writers. The media and photographers were very much attracted to gangs.

Dr. Maltsev: If you take a look at this phenomenon as a scientist, what do you think attracts these people to gangs?

Dr. Steinberg: I think the whole story of Nongoloza is very exotic and that has very attractive value. The fact that the gangs are so very visual, the tattoo culture in particular. Also as long as anyone can remember the media was attracted to violence, and this is a culture that celebrates violence. For all of those reasons these gangs attract a voyeuristic eye. Once the gangs are on a business of selling something, they sell their violence, they sell their images, their stories, so a commercial relationship is established very quickly.

Dr. Maltsev: There is one more interesting moment. Any criminal tradition has its own religious philosophy and there is no doubt in this. However, in the case of Cape Town gangs, their religious philosophy is very contradictory and there are multiple versions of its interpretation. Why is that so?

Dr. Steinberg: I think what binds the whole tradition together is the story of Nongoloza himself, although I think the meaning of the Nongoloza story has changed over the years. In the early years of the gang the most important thing about Nongoloza is that he fought colonialism. I think in later years of the gangs starting in the late 1980s who Nongoloza is begins to change and he becomes much more of a capitalist, he becomes a bandit and an outlaw who is able to make money. And I think that this is quite an important change, which has its reflection in the articles, books and today’s understanding of what Number gangs are.

Dr. Maltsev: And the last question if you may. What are the stages of South African criminal tradition formation in your opinion? Which periods can we underline in the history timeline?

Dr. Steinberg: I haven’t given enough thought to that, I guess something I am interested in is how these Number gangs 26, 27 and 28 became a national phenomenon in gangs across the country. I am interested in this because, it is not just the space that they have crossed, it was many different cultures, different racial groups, different languages. The fact that they have managed to become a national institution across the country is for me really fascinating and I am guessing what propelled it was the extraordinary story of Nongoloza himself. I think it was the power of narrative which allowed the gangs to evolve into being everywhere. I would love to have done such research that could trace how that happens.

Dr. Maltsev: I must admit that currently I am trying to conduct this kind of research and planning to carry on during the 2018 expedition to Cape Town.

Dr. Steinberg: That sounds like a very fruitful path to take.

Dr. Maltsev: Thank you, hope to see you soon and continue our discussion.

Dr. Steinberg: You are welcome. I wish you good luck with the research and if you need anything else please be in touch

“It is better to face the truth beforehand, than the failure after a while”. Anonymous