Plinio wrote: "He who wishes to consider in detail the quality of water used for the public baths, (…) the distance which they traveled, the conduits that were built, the valleys that were obliterated, needs to recognize that nothing more marvelous has ever existed in the world." Undoubtedly a masterpiece of engineering, but above all else an example (amongst the most eloquent) of how advanced the roman civilization was two thousand years ago.

Other than its engineering magnificence, Plinio's description gives us a sense of how well widespread the baths were in the Rome of two thousand years ago. The city was in fact scattered with grand and splendid bathhouses that all had access to. Unlike today, the baths were a public service at people's disposal with no class distinctions, and thus constituted a fundamental infrastructure that made Rome, with its two thousand inhabitants (the most populous metropolitan city in history until the industrial era in the 19th century), a healthy place with a remarkable level of hygiene for its inhabitants.

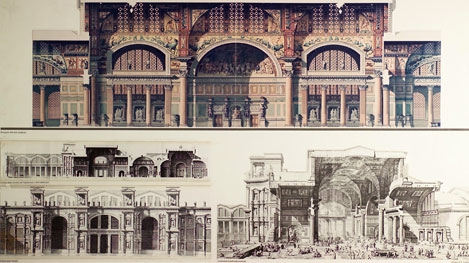

Baths of Diocletian, Rome

The baths of Traiani and the nearby Caracalla baths at the slopes of the Aventino were two vast and imposing building complexes built by Diocletian in the third century. The largest in Rome to date, they are spectacular monuments that easily allow us to imagine their original state even in their ruins. It is for this reason that they had a determining influence in the architectural history of the West.

After the fall of the empire, the barbarian invasions and then the Church taking over the state, the decline of the bathhouse concept entailed, resulting in abandoned buildings that quickly turned into ruins. It wasn't until the 1920s, in a cultural climate that looked to antique roman monuments with admiration, that the concept resurfaced with proposals with several projects of imposing new bathhouses: Vincenzo Fasolo proposed the "Centro Sanitario e Sportivo" in the area of today's piazza Risorgimento that was based on the ancient model adapted to the changing modern needs. Even architect Alessandro Limongelli, followed by the visionary Armando Brasini, proposed buildings that were designed according to the Roman baths with imposing spaces connected by grand vaults over pools and spaces adjusted to different temperatures.

A representation of the interiors of the Baths of Caracalla in the Ancient Rome

Between the 1800s and 1900s, New York was a densely populated industrial city and, like ancient Rome, many of its inhabitants lived in squalid homes that lacked the basic infrastructure for daily hygiene. In line with the progressivist attitude of the times, the city thus started to support the construction of what would then be defined as the "bathhouse". Like Caracalla and Diocletian two thousand years prior, the mayors of New York City were dedicated to the promotion and creation of large public baths for reasons quite similar to those that made the ancient emperors create the baths. Furthermore, even if New York's bathhouses were not destined to becoming architectural marvels, they became a significant infrastructure for the city.

In 1897, the bathhouse was considered one of the most important services that progressive America offered its citizens. Personal cleanliness had become a necessity, both for public hygiene and, at a more personal level, for a kind of social acceptability as it was thought to demonstrate education and good character. Hygiene was finally a right for all citizens in a country that, at the time, was giving refuge to immigrants coming from all over the world and looking for social integration above all else. There existed a perceived reciprocal relationship between moral character and cleanliness; bathhouses were therefore the most effective way to promote public hygiene and civil rights.

The first successful bathhouse in the United States was built in New York in 1891. Named 'The People's Bath', it was located in the Lower East Side, north of Grand between Centre and Mulberry, in an area with a high concentration of immigrants. It was the result of the efforts of a coalition of private associations of the city. An inscription on a large arch above the entrance proudly proclaimed: cleanliness is next to godliness. This building signified, at the time, a profound innovation: unlike its predecessors, above the then common bath areas, it also had showers. This characteristic, which today may perhaps seem of little importance, represented an efficient and functional novelty: the use of the shower drastically reduced the amount of water used and space needed. Additionally, for the first time, materials like cement and metal were introduced to replace wood, proving to be more economical and safe.

People stand in line in front of Rutgers Place Free Public Bath; July 27, 1912

From that point on, the public bathhouse spread across the country and, like many other innovations of the time, truly developed a nationwide network for the sharing of ideas and best practices, disseminated through print media. The model quickly solidified itself: the building, usually two stories, was often built out of light brick with stone finishing. The facades were light and colorful to impress upon the neighborhood. The architects focused on functionality with a particular attention to circulation and, naturally, to the sanitary services, with the objective of creating an efficient building that can satisfy the large influx of people.

It's interesting to note how multiple echoes of the classical world are found across the models of public buildings in the America of the late Victorian period. There is a sort of irony in realizing that, in the years that Penn Station was being built in New York, although based on the Baths of Caracalla, bathhouses became examples of 'less noble' buildings, akin to closed markets.

The analogy, with two thousand years in between, was certainly reinterpreted in all of its variations, but is indelible from these two metropolises: New York and Rome. In different moments of history, these cities were world capitals and had to confront issues deriving from their global position that called a large number of immigrants; it is interesting to see that, in such different times, similar solutions were adopted.