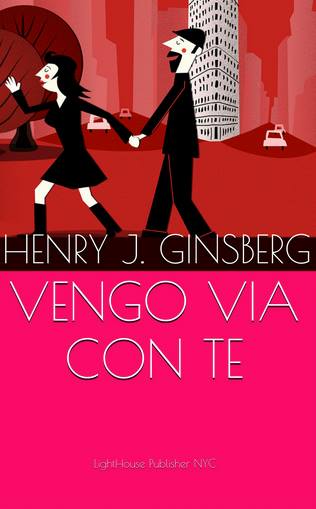

Questa settimana, anziché la consueta recensione domenicale di Marco Pontoni, che pubblichiamo ormai da quasi un anno nella rubrica Walk on the Book Side, diamo spazio proprio… al recensore. E' uscita infatti qualche giorno fa in Italia, come ebook, la nuova edizione della sua raccolta di racconti Vengo via con te – storie d'amore e latitudini, firmata con lo pseudonimo di Henry J. Ginsberg (che la dice lunga sul suo amore per la letteratura americana). Il libro è dunque già disponibile su Amazon (prezzo Kindle: 4.19 Eur) e gli altri store.

In questi giorni la stessa raccolta è in uscita anche negli Stati Uniti, in formato sia cartaceo che elettronico, con il titolo Run Away with Me. A curarla è Lightouse Publisher, giovane casa editrice “hipster” di New York, specializzata in narrativa di viaggio, che si distingue per il suo impegno nella ricerca di nuovi autori. Negli Usa l’edizione cartacea sarà distribuita principalmente nel circuito delle librerie Barnes & Noble.

In questi giorni la stessa raccolta è in uscita anche negli Stati Uniti, in formato sia cartaceo che elettronico, con il titolo Run Away with Me. A curarla è Lightouse Publisher, giovane casa editrice “hipster” di New York, specializzata in narrativa di viaggio, che si distingue per il suo impegno nella ricerca di nuovi autori. Negli Usa l’edizione cartacea sarà distribuita principalmente nel circuito delle librerie Barnes & Noble.

Una città, una storia. Potremmo sintetizzare così la formula del libro di Henry/Marco. Da New York a Londra, da Parigi a Palermo, da Istanbul a Roma, da Chicago a Rio, da Gerusalemme a Bruxelles, al centro di questi racconti sono ritratti di persone, luoghi, momenti, situazioni, emozioni. Il tutto attorno al tema dell'amore, declinato in tutte le sue espressioni e manifestazioni.

Pubblichiamo qui il racconto dedicato a New York: l'originale in lingua italiana e, in anteprima, per gentile concessione di Lighhtouse, la traduzione in lingua inglese (traduttrice: Marta Mondelli; proofreading: Alyssa Nadella).

New York di Henry J. Ginsberg / Marco Pontoni

Sono in viaggio di nozze a New York. Il primo giorno hanno litigato perché lei ha vomitato in mezzo alla 47a strada, luogo per lui sacro perché ospitava la Factory di Andy Warhol.

Lei è incinta, ma si era detta pronta ad affrontare il viaggio. Lui adesso medita sul fatto che è la prima volta che vede New York e sicuramente non potrà fare tutto quello che avevano pianificato leggendo la guida ("insieme, di comune accordo").

Le tiene il muso fino a cena. Gli passa solo in un Burger King semivuoto. Lei è depressa, lui si sente in un quadro di Hopper, quindi felice.

Lei è a New York ma pensa a casa, al gatto, alla toxoplasmosi, alle cose che ha lasciato per aria e che ritroverà appena tornata.

Il giorno dopo optano per il Central Park. È una giornata di sole, passano il tempo sull'erba a riepilogare i nomi che potrebbero dare al loro bambino, o bambina.

"Paul", dice lui.

"Riccardo", dice lei. "Dennis".

"Michele".

"E se fosse una bambina… Edie". "Al massimo Miranda". "Vedremo". "Oppure Carmen!".

Ridono, per chiuderla lì. Lei va a comperare un gelato in un chioschetto.

L'Empire State Building. Il Palazzo di Vetro. Il Village. Si spostano un po' in metropolitana e un po' in taxi. Se camminano, lei deve fermarsi frequentemente. Tutto è un po' più costoso di quello che si erano immaginati.

Una sera lui le chiede il permesso di andare a vedere uno show all'Apollo. Lei rimane in albergo a leggere una rivista che elenca tutti gli spettacoli che ci sono quella settimana in città.

La fotografa su una panchina famosa sotto il ponte di Brooklyn, una panchina ripresa in un'infinità di film. Lei si sente tutt'altro che una bellezza e gli chiede di cancellarle, quando gliele fa vedere. Poi è lui a voler essere fotografato, se ne fa fare una quantità, lì vicino un nero suona il sax, gli domanda in prestito lo strumento per avere una foto sotto al ponte con il sax, e poi vuole una foto con il sax e con il nero.

Gli sembrava una buona idea fare l'amore ma è stanca, così esce a fare un giro dell'isolato, uno scroscio di pioggia lo sorprende, si rifugia in un caffé, all'uscita un litigio fra due taxisti, uno stormo di uccelli fra i cirri, c'è il cielo che preme, sui tetti dei grattacieli, le scale esterne per fuggire, gente, semafori, insegne, odore di mare, pubblicità.

Una sera vanno a trovare dei lontani cugini di lui, a Brooklyn. Non li avevano avvisati della loro presenza nella Grande Mela se non il giorno prima, per non farsi monopolizzare tutta la vacanza. Veramente è stata lei a mettere le mani avanti, lui pensa che questi cugini, immigrati di seconda generazione, sono davvero simpatici, pensa che è un peccato non essersi fatti ospitare da loro, a costo di dormire fuori Manhattan. Non sanno quasi nulla dell'Italia e, unico difetto, non amano Spike Lee.

Una sera a lui sembra di vedere Woody Allen entrare in un club, è molto esaltato. Lei vorrebbe che riservasse tanto entusiasmo anche ad altro, le sembra di avere sposato un ragazzino, e si ricorda che era così anche prima, solo che prima lo trovava divertente, avevano sempre un sacco di cose di cui parlare. "Comunque – gli dice – non poteva essere Woody Allen, è a Cannes per il festival".

L'ultimo giorno lui è pentito, avverte un senso di perdita, l'occasione sprecata di visitare con sua moglie la città dei suoi sogni. La porta a fare shopping ma non possono permettersi oggetti piccoli e costosi e non hanno spazio a sufficienza nelle valigie per cose più ingombranti. Carmen e Vincenzo, i loro amici del cuore, gliel'avevano detto, di portarsi poca roba da vestire. Di chi è la colpa? "Sua", pensa lui.

"È che sono incinta, se non te ne fossi accorto", dice lei, dopo avergli letto nel pensiero. "Non sei mica la prima che aspetta un bambino", dice lui.

Lei va in bagno a piangere.

All'aeroporto finalmente si rilassa. Stanno per tornare a casa, ci sono molte cose da fare, il lettino che gli hanno regalato da montare, e poi la macchina dal meccanico, per quella spia che non si spegne, dev'essere solo un nulla, ma meglio non farsi lasciare a piedi mentre si aspetta un bambino, medita lui, giudiziosamente.

Lei gli appoggia la testa sulla spalla. Sono così, sono diversi, sono due esseri umani completi, ognuno a suo modo, non c'è scritto in nessun manuale come farne di due uno, e forse non è possibile. Ma questo amore durerà. A dispetto del disastroso esempio dei loro genitori, a dispetto delle vecchie storie che si sono lasciati alle spalle, a dispetto del fatto che a lui piacciono gli hamburger e a lei il sushi, a dispetto del fatto che lui odia la classica e invece lei sostiene che faccia persino diventare più intelligenti, cosa che non si potrebbe argomentare alla leggera di gruppi come Television o Talking Heads, peraltro defunti da tempo, lei si dice che, sì, questo amore nato per caso, come tanti, come tutti, questo amore cresciuto in fretta sull'onda dell'entusiasmo e delle carezze, questo amore di borbottii e facce scure, ma anche di mani, occhi, baci, carezze, gite al lago e ore e ore di computer, è un amore destinato a durare.

New York by Henry J. Ginsberg / Marco Pontoni

They’re on their honeymoon in New York. On the first day, they fight because she vomited in the middle of 47th street, a sacred place to him because that’s the address of Andy Warhol’s Factory.

She is pregnant but said she was ready to make this trip. Now he is considering that this is the first time he sees New York and for sure he won’t be able to do all the things they planned while reading the guide (“together, in agreement”).

He is upset at her till night and gets better only in an almost empty Burger King. She is depressed. He feels like he is inside a Hopper painting: happy. She is in New York but thinks about home, the cat, the toxoplasmosis, the things they left there and that she will find again once she is back. The day after, they decide to go to Central Park. It is a sunny day: they spend it on the lawn; going through a list of names they can give to their son, or daughter.

“Paul” he says.

“Riccardo” she says.

“Dennis.”

“Michele.”

“And if it’s a girl… Edie.”

“Maybe Miranda.”

“We’ll see.”

“Or maybe Carmen!”

They laugh and stop talking. He gets her an ice cream at a vendor.

The Empire State Building. The UN building. The Village. They use both subway and taxis. If they walk, she needs to stop frequently. Everything is slightly more expensive than they thought.

One night he asks her permission to go and watch a show at the Apollo Theater. She stays at the hotel and reads a magazine listing all the shows in the city that week.

He takes a photo of her on a bench under the Brooklyn Bridge: a famous bench that appeared in endless movies. When he shows her the photo, she doesn’t like herself in it and asks him to erase it. Then he wants to be photographed and has many pictures taken. There is a black man who plays the sax nearby: he asks to lend him his sax to have a photo under the bridge with the sax; and then he also wants a photo with the black man and the sax together.

He thought it was a good idea to make love, but she is tired. So he leaves and walks around the block and the rain catches him by surprise. He finds shelter inside a café. When he leaves, a fight between two taxi drivers, a flock of birds among the high wispy clouds. The sky presses on skyscrapers, fire-escapes stairs, people, traffic lights, signs, smell of the ocean, advertisement.

One night they visit his distant cousins in Brooklyn. He didn’t tell them he was coming to the Big Apple till the day before, in order not to have his entire vacation monopolized. Actually, it was her who was cautious. He thinks that these second generation cousins are very nice and that it is a pity not to stay at their place, even if it is outside Manhattan. They don’t know almost anything about Italy and their only flaw is that they don’t like Spike Lee.

One night he thinks he has seen Woody Allen entering a club and is very excited. She would like for him to be excited also about something else and thinks that she has married a kid. She remembers that he’s always been like that, but before it seemed endearing: they had so many things to talk about. “Anyway, – she says to him – that couldn’t have been Woody Allen: he’s in Cannes for the festival.”

The last day, he is regretting to have taken this trip: he feels a sense of loss, of have wasted the opportunity of visiting the city of his dreams with his wife. He takes her shopping, but they can’t afford small and expensive objects, and they don’t have enough room in their luggage for large items either. Carmen and Vincenzo, their best friends, suggested them not to bring many clothes. Whose fault is that? “Hers” he thinks.

“I’m pregnant, if you haven’t realized that” she comments, anticipating his thoughts. “You’re not the first one to be expecting a child” he says.

She locks herself in the bathroom and cries.

At the airport she finally relaxes. They are about to come back home. There aren’t so many things to do: assembling the bed for the baby, bringing the car to the mechanic for that signal that doesn’t turn off. It is probably nothing, but it’s better not to have a car problem when she is expecting – he wisely concludes.

She rests her head on his shoulder. They are this way: they are two different, complete human beings, each separated, and there is no rule explaining how to make one person out of two people, and maybe that’s not possible. But this love will go on, despite the disastrous example of their parents, despite the old affairs they left behind, despite the fact that he likes hamburgers and she likes sushi, despite the fact that he hates classical music while she believes that it makes people smarter, something that can apply also to rock bands like Television or Talking Heads, even if they’ve been deceased for a while now. She says to herself that, yes, this love born by chance (like many – like all of them), this love grown rapidly, with enthusiasm and caresses, this love made of mumblings and long faces but also of hands, eyes, kisses, trips to the lake and hours and hours at the computer, this love is destined to last.