The Treaty of Paris, better known in the United States as the Kellogg-Briand Pact, which bans all wars from the face of the Earth, was finally signed today by 15 nations, including some of the most belligerent nations, such as the United States, England, France, Germany, Italy and Japan. But you, reader, must not get too excited this this, for this treaty was signed in Paris 79 years ago on August 27, 1928. I must confess that I myself never knew that war was in fact, illegal and banned until a few days ago when I read about it in David Swanson’s book, When the World Outlawed War (Charlottesville, VA, 2011), from which I take most of the content for this article.

On August 27, 1928, the United States, France, Great Britain, Germany, Belgium, the Dominion of Canada, the Commonwealth of Australia, the Commonwealth of New Zealand, the Union of South Africa, the Irish Free State, India, the King of Italy, Japan, Poland and the Czechoslovak were the initial signatories of the Treaty. They “solemnly declare” [d] in the name of the people they represented “to condemn recourse to war for the solution of international controversies.”

(The Treaty was named after the then US Secretary of State Frank Kellogg, and the Minister of Foreign Affairs of France Aristide Briand).

The Treaty of Paris is short and clear. It comprises a brief Preamble and only three (3) short Articles:

Article One textually states: “The High Contracting Parties solemnly declare in the names of their respective peoples that they condemn recourse to war for the solution of international controversies, and renounce it, as an instrument of national policy in their relations with one another.” (Emphasis mine).

Article Two declares that…. The parties agree that the settlement or solution of all disputes… of whatever nature or of whatever origin they may be, which may arise among them, shall never be sought except by pacific means.” (Emphasis mine).

Article Three is divided into 3 short paragraphs, in effect assigning Washington, to record and to inform other nations the names of nations that would in the future sign the treaty. It gave the United States no other specific task or responsibilities, and this was done upon direct request from the US delegation.

From the United States’ part, on January 15, 1929, the US Senate voted 85 to 1 in favor of the Kellogg-Briand Pact. The outgoing US President Calvin Coolidge signed the Treaty into law; and on July 24, 1929 the newly elected President Herbert Hoover declared the treaty in force. As I write, August15, 2017, the US Department of State, according to Swanson, still lists the Treaty in force, and has over 70 countries as subscribed members. Despite all of this, lamentably for the human race, war still rages on as unabated as ever!

The doleful questions that come to mind are many; but we should simply try to answer: 1) What happened to the Peace treaty that millions of people all over the world (especially in the US) fought so arduously to get passed? (2) Why it did not achieve what it had clearly spelled out to achieve?

The Peace Movement after the end of WWI.

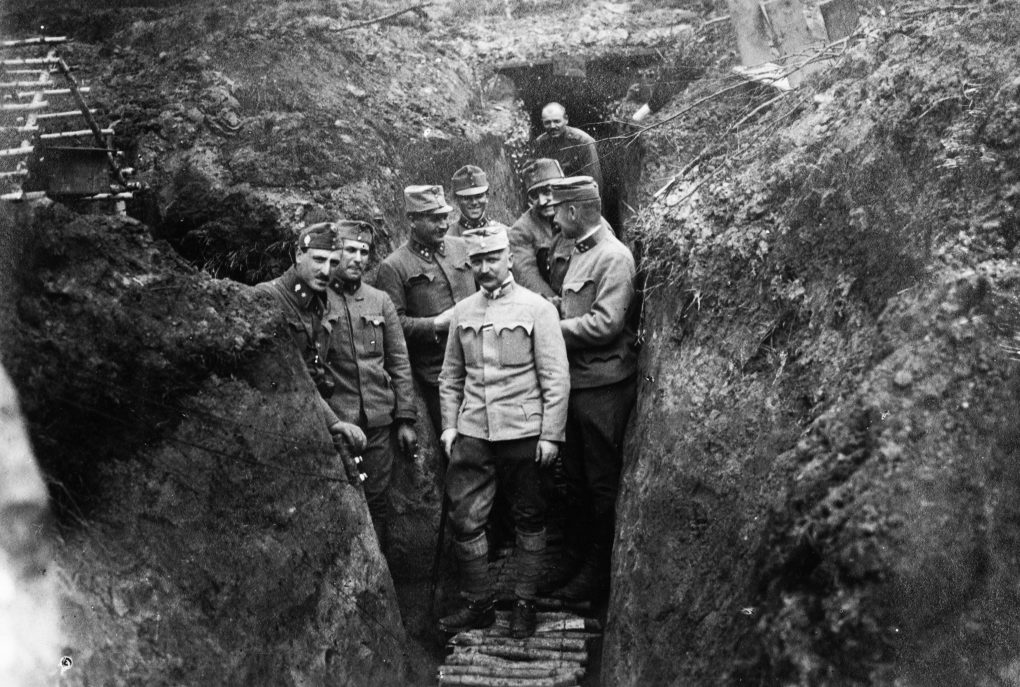

David Swanson, in his above cited book, reports that during the twenties, the “people of the world,” after the great disillusionment of World War I, its costs in term of human lives and its total futility, tries to give a sense of that war. To this end, he quotes Thomas Hall Shasta’s book, Give the People Their Own War Power, (1927): “[O] n November 11, 1918, there ended the most unnecessary, the most financially exhausting, and the most terribly fatal of wars that the world has ever known. Twenty millions of men and women, in that war, were killed outright, or died later from wounds. The Spanish influenza, admittedly caused by the War and nothing else, killed, in various lands one hundred million persons more.” (P. 12)

Peoples’ sentiments against future wars reached the offices of their representatives directly and so furiously that the leaders could hardly ignore them. The propaganda that had called young people to take up arms and to go to fight in a war that “will end all wars,” caused unprecedented millions of people from around the world to rise almost unanimously with their marches, protests, and petitions. And the protesters and petitioners were not just the common people: Several great foundations dedicated money and efforts against future wars: The World Peace Foundation and the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace gave their funds to the Peace Movements and made their voice heard loudly. Andrew Carnegie himself sought to ‘hasten the abolition of international war, the foulest blot upon our civilization.’ (p.17). Writers, newspapers editors, philosophers and intellectuals of all disciplines rose against future wars.

Swanson reports that literally hundreds, if not thousands, of Peace Movements were activated, in the US alone; some of them were, just to name a few: The American Friends Service committee, the Association to Abolish War, the Intercollegiate Peace Association, the Catholic Association for International Peace, War Resisters International, the [Women’s] National Committee on the Cause and Cure of War, the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, Women’s Peace Society, Women’s Peace Union of the Western Hemisphere and many-many others.

It seems that women were relentless in pressuring US Senators to ratify the Kellogg-Briand Pact (Paris Treaty of 1928). Most of the governments’ officials who signed the Treaty, and many other elected representatives, both in the US and France, originally had been opposed to idea of declaring war illegal. They were practically obliged to join in order to answer the tremendous vociferous demands made by their local constituencies. The French Prime Minister Aristide Briand himself had initially publicly addressed the American people publishing a letter through newspapers, bypassing American diplomatic channels, declaring that “France would be willing to subscribe publicly with the United States to any mutual engagement tending to outlaw war” (Emphasis mine).

Prime Minister Briand, later, insisted that he had meant it to be only a bilateral peace pact between the US and France. Obviously, he had wanted to bring the US to France’s side against any future conflict it might have with the more belligerent Germany, and perhaps so that it, France, could still pursue her colonial conquest unabated. But France was not the only nation, who, while advocating peace, also tried to preserve its right to maintain open belligerent options for future possible colonial adventures.

For example, the United States, the same week the US Senate voted for the treaty for peace 81 to 1, ironically, also appropriated, in response to President Coleridge’s request, the largest military expenditure ever to enlarge the US navy since World War I (P. 99); Germany would soon begin to build weapons of aggression secretly in violation of the Versailles Treaty of 1918. Japan invaded Manchuria (1931), Italy invaded Abyssinia (1933), and even the US was not standing by idly either; in addition to enlarging its navy, it also was already at war with Nicaragua (1926-1933). It landed forces in China (1932), It had a show of force in Cuba (1933), the US Marines landed in China (1934), without mentioning its acquisition of military bases abroad, and the selling of weapons to Britain and Russia.

But it was known from the inception that the Kellogg-Briand Pact was weak and that it would soon be broken. Salmon Oliver Levinson, a lawyer by profession and the organizer of the Outlawry of War (that eventually became the spearhead of the people’s Peace Movements, which represented the aspiration of millions of people) had advocated that international disputes were to be settled in a court of law, and the institution of war to be rejected just as slavery and Prohibition laws had been. (P. 26). In addition, US Senator William Borah, Chairman of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, on February 13, 1923, introduced a resolution in Congress that would call for the (1) outlawing of war, (2) the codification of international law, and (3) the creation of a world court (p. 50). But, as usual, the US Senate diluted the proposal rendering it perfectly innocuous, and easily open to interpretation that would allow war to persist. Some senators, in fact, did protest during the debates. Senator William Bruce from Maryland, for example said: [The Kellogg-Briand Pact was] “about as effective as to keep down war as a carpet would be to smother an earthquake.” He turned out to be prophetic.

The Treaty, nonetheless, once watered down, was presented before the entire Senate for vote. Due to tremendous popular pressure, one Senator who voted “yes” for the Treaty, even made known his concern that he would be “burned in effigy back in his state,” had he not done so. (P.140). The Kellogg-Briand Pact was passed almost unanimously.

Who is at fault that the international people’s will for “No More Wars” was willfully reduced to an innocuous and useless law? To be perfectly clear, it’s not a particular senate or government. They were all untrue and responsible for it. Unfortunately, the governments, not wanting to qualify them “warmongers,” still behave like a bunch of bullies. They continually disregard their people’s will. It is clear to me that in 1928, most of US Senators, as well as the other Heads of States, for “30 pieces of silver” misled and betrayed their own people shamelessly. If only war were a non-consequential play, and not the cause of utter destruction, and the most horrendous human tragedy!

A critic has rightly said that governments were created to incur war, not peace. Unfortunately for us, even under the threat of thermo-nuclear warheads, this statement continues to be true. But how long, I do ask, will it take for the people of this world to finally say “enough is enough,” and find a way to deny war powers to their governments effectively, before they destroy us all in the most atrocious, humiliating and self- destructive holocaustic manner?