When you arrive in Chambersburg you would never think you are in the capital of New Jersey. The difference between the well-lit streets, the impressive buildings, the golden dome of the New Jersey State House in the center of Trenton, and the boarded-up houses in disrepair in a decaying Chambersburg is evident.

“And yet Chambersburg wasn’t always like this” is what Italian-Americans will tell you, those who have stayed in this neighborhood in the southern part of the city and the ones who spent a large part of their lives here and then moved to more residential areas. They are 60- and 70-year-olds men and women, who, at the beginning of the 60s, attended the elementary schools set up inside the two Catholic churches in the city square dedicated to Christopher Columbus. They were born there or took their first steps as Italians in America there 50, 60 or 70 years ago.

Community

Chambersburg was just one of the many Little “Italies” in America for years; it was the hub of a community of Italian emigrants who came to the United States in search for a better future. “Community” is the key word to understand what this area once was. It wasn’t just a “neighborhood;” here everyone knew each other by first and last names, they stayed together, they helped each other. On Hudson Street no one spoke English, only the dialects of Sicily, Naples and Calabria. There were village festivals and religious processions. There were Italian food and bakeries, butcher shops and Italian grocery stores. And obviously, there were restaurants which were more than simple places to eat, but true family extensions. Like the Taylor Restaurant, whose owner Tony Falvo never learned English because he was a little lazy, or maybe because he wanted to keep his cultural identity. It was here that many spent time happily after a week of hard work.

Italian Working Class

Work was the reason you lived in Chambersburg. The working class lived here, those who woke up every day at three or four in the morning to go to work in factories in Trenton and the surrounding areas; the same working class that provided meaning to the famous expression that can still be read on the Lower Free Bridge, “Trenton Makes, the World Takes.” In the Roebling Building, for example, the factory where steel was forged to build the Brooklyn Bridge and the Golden Gate Bridge of San Francisco. Or the cigar factory where many Italian women worked. Or even the Ice House that remained operational until the arrival of the refrigerator, the factory where many young Italians worked during the summer to save pocket money to go to the movies or to a bar at night.

The American Dream

Italians abandoned Chambersburg because of the American Dream. The dream of a house, a garden to take care of with a picket fence and a garage. In other words, they wanted to find a private property in the neighboring areas. Then, with the passing of time, the factories closed and for some it was time to move away.

Because of this, the Italian community in Chambersburg began to diminish and those who are left are thinking of moving away. “Now, everything has changed, nothing is like it once was,” said Joe, 66 years old, 40 of which were spent in Chambersburg. Before him, his grandfather arrived there, in 1903, from Sant’Antimo, near Naples. His grandfather and grandmother opened a bakery, The Colonial Bakery, where many Italians worked. “There are no more Italians, now there are the Spanish,” he explains. The community has changed. There are those who come from Mexico, Guatemala, Costa Rica, Colombia. Here people generalize, calling them the “Latinos” without giving much importance to their origin. Different ethnicities, same dream. The Dream.

History Repeats Itself

The signs of the Italian stores have been replaced by more exotic names. No more Rossi’s, Marsilio, La Gondola, De Lorenzo, but Chapala II or Montezuma. In the local churches, no more masses are in Italian: today in St. Joachim Church, the main church in the area, Spanish is predominantly spoken. From “the burg,” the way the Italians would call it, to the “Barrio.” From the ‘Burg to the Barrio. A Portrait of Chambersburg and Trenton is also the title of a documentary filmed by Susan Ryan, who in 45 minutes tried to explain what happened here in the last 30 years: little integration, tension between different communities living side by side, a series of many microcosms fighting over the same space.

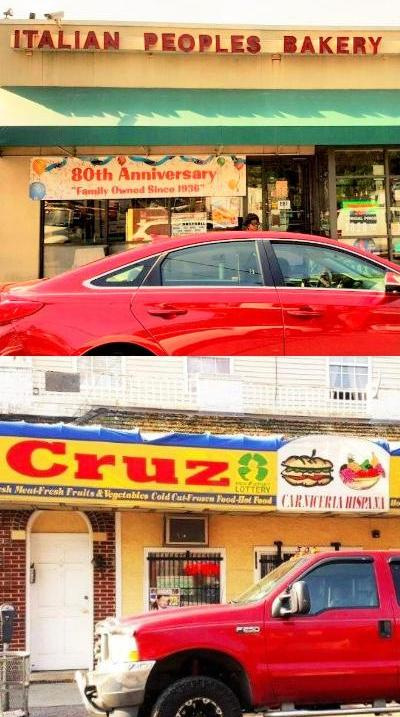

At one time in Chambersburg there were three Italian bakeries, and the one in the first image above is the last bakery that remains open. Today, the signs with Italian names are replaced by those of Hispanics.

It is history repeating itself, it’s the same old story, that of the Other, who is different and inspires fear.

“Chambersburg is no longer a safe area, it’s dangerous,” declared some time ago into the microphones of NJTV News, Jimmy Kamies, owner and chef of the restaurant Amici Milano, one of the most renowned in the area. Many think the same way, which is why they end up moving away. They forget that when they arrived some time ago, they too were not welcomed immediately. Yet they criticize the Latinos who moved there for the same reasons they did.

“They leave because of us, but I don’t understand why, we are here to work,” says Juan, who came from Santander and today works in a pizzeria by the slice. Unlike other residents, people from the Latino community don’t have any desire to talk, they prefer not to get into trouble and to just work. They are aware that they live in a racist neighborhood where they are not welcome, but they don’t care, or rather, they have other priorities. Paradoxically, many are the manpower behind Italian-American companies. Because for them, Chambersburg is a launching pad. From the same spot, where others many years ago got their first start. With the same desire as their grandparents and great grandparents: to pursue the American Dream.

Translated by Rosanna Coviello and Rosemarie Di Filippo