As Stefano Vaccara observes early in his new book, Carlos Marcello: The Man Behind the JFK Assassination, “For a major assassination to be called a Mafia ‘hit,’ five ingredients are required: motive, means, opportunity, blackmail of any potential avengers, and a favorable political context: the target is a threat to the establishment.” Vaccara then states, “The assassination of President Kennedy fulfills all five requirements … JFK was killed as a result of a conspiracy by powerful organized crime figures. This book will provide the motive, the method and the proof beyond a reasonable doubt as to how and why he was murdered in Dallas in 1963.”

That’s a big and startling claim to make, but one I find quite convincing, far more so than the “lone gunman” conclusion of the Warren Report, the official – but hardly credible – account of Kennedy’s assassination.

Vaccara’s important book identifies Carlos Marcello, the powerful Mafia chief of New Orleans, as the mandante of the assassination, its chief organizer. Marcello – born Calogero Minacori in Tunis, to Sicilian parents – is far less known to the public than such notorious gangsters as Al Capone, Lucky Luciano, or John Gotti. Yet he wielded far more power than any of them, and for many more years.

Organized crime becomes “Mafia” when criminal enterprises engage in relations of reciprocity with the establishment – politicians and public institutions. And Carlos Marcello was a master of building and maintaining those relationships. The Mafia don of New Orleans was physically unprepossessing – only five-feet tall, he was known as “The Little Man” – and basically illiterate. But Marcello, with intelligence, cunning and no little violence, built a criminal empire – aided and abetted by elected officials, police departments, prosecutors, and judges – that extended from New Orleans throughout the state of Louisiana, and beyond, to Mississippi and Texas. And that presence in Texas would be crucial to Marcello’s plans to eliminate President John Kennedy – which would have the effect of ending the aggressive investigations of Marcello and the Mafia led by the president’s younger brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy.

Marcello, like a true Sicilian Mafia boss, sought out alliances with politicians, but he never approached them hat in hand. Giovanni Falcone, the Sicilian magistrate assassinated by Cosa Nostra in 1992, described this aspect of mafioso behavior: “If it is true that a fair number of Sicilian politicians have been, to all intents and purposes, adepts of Cosa Nostra, it is also true that within the Mafia as an organization they have never enjoyed particular prestige because of their political origins. In short, Cosa Nostra is so strong, compact, and independent that it can speak and make alliances with whomever it chooses, but never from a subordinate position.”

As a criminal chieftain who commanded a vast network of business and political connections, Marcello recalls no one so much as the figure who has come to be known as synonymous with “Mafia” – the fictional “godfather,” Don Vito Corleone. Recall the famous scene in The Godfather when, at the meeting of the heads of the “five families,” one disgruntled gangster complains that Corleone “had all the judges and politicians in his pocket and refused to share them.”

Marcello’s vast wealth and power ensured that he would never be subordinate to anyone. Vaccara notes that by the end of the 1950s, Marcello, with more than $1 billion in business in New Orleans and outside the city, was the richest and most powerful Mafia boss in the country, and that his organization was Louisiana’s single largest industry. Despite all this, Marcello is an obscure figure to most Americans.

Stefano Vaccara is not the first to connect Carlos Marcello to JFK’s assassination, but it took a Sicilian journalist like him to explain Marcello’s mentality and behavior, and how the assassination bears all the earmarks of a Mafia plot that would result in a “cadavere eccellente,” an illustrious corpse.

Stefano Vaccara is not the first to connect Carlos Marcello to JFK’s assassination, but it took a Sicilian journalist like him to explain Marcello’s mentality and behavior, and how the assassination bears all the earmarks of a Mafia plot that would result in a “cadavere eccellente,” an illustrious corpse.

Vaccara’s book owes a substantial debt to two previous ones, John Davis’ Mafia Kingfish: Carlos Marcello and the Assassination of President Kennedy by Organized Crime (1989), and, more recently, Legacy of Secrecy, by Lamar Waldron and Thom Hartmann (2009). Davis’ book is a remarkable piece of investigative journalism. But it also is quite long and complicated, and it’s not always easy to follow its narrative skeins. Vaccara’s book has the virtue of condensing much of Davis’ research, and information from other sources, into a clear, logical, and engrossing narrative.

Vaccara methodically reviews and synthesizes the evidence that what happened in Dallas on November 22, 1963 “certainly was a Mafia hit.” What is puzzling is the fact that given so much evidence pointing to Carlos Marcello’s involvement, that evidence has not been followed to its logical conclusion. Vaccara notes that the case “would remain ‘frozen’ for fifteen years after the Dallas tragedy.” And even after a two-year investigation by a Congressional committee established that Carlos Marcello “more than anyone else should be singled out as the number one suspect in the Kennedy assassination,” that conclusion “failed to move America’s public consciousness.”

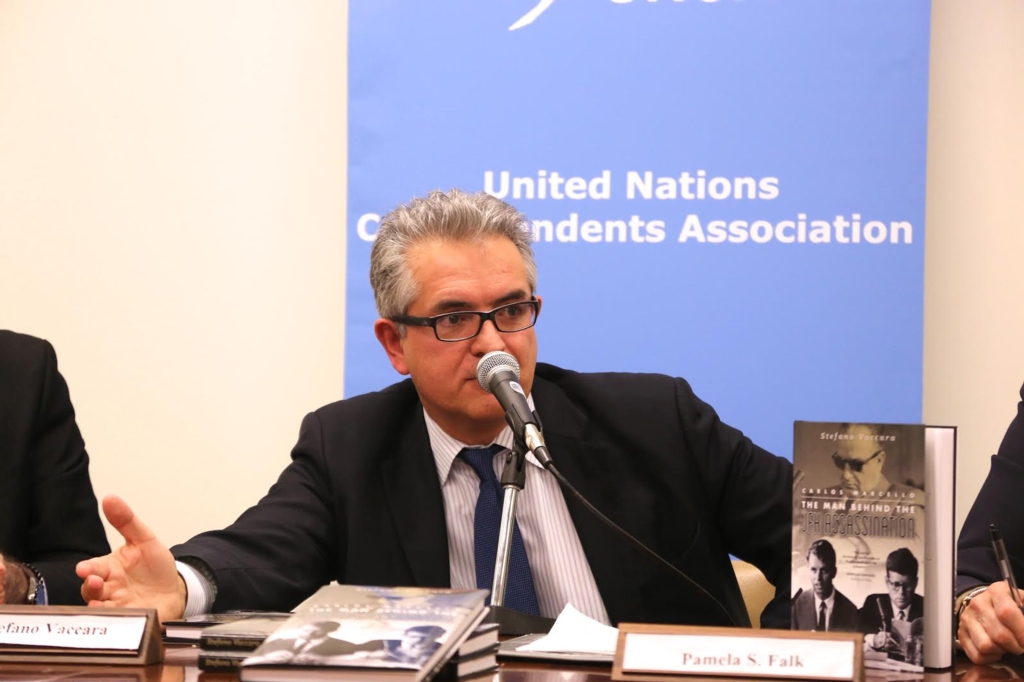

Stefano Vaccara, journalist, author: Carlos Marcello, the Man Behind the JFK Assassination

Besides the clarity of Vaccara’s account and his particular insights as a Sicilian journalist, the book has the virtue of not being filiopietistic but rather candid and honest, and not only about the Kennedy assassination and Marcello’s role but also about issues that some Italian Americans would prefer not to acknowledge. Vaccara, although he now lives in Brooklyn and is a U.S. citizen, originally is from Palermo, and as a Sicilian journalist who has covered Cosa Nostra, he is unafraid to go where Italian American anti-defamationists fear to tread. It’s not that he’s insensitive to Italian American concerns about Mafia stereotyping and ethnic defamation. He’s just not bound by them.

Take, for example, the history of Sicilian migration to New Orleans. There have been books that documented that history, focusing on the immigrants’ struggles and their eventual assimilation into New Orleans’ rich ethnic gumbo. The typical narrative arc goes like this: they came, they were poor and mistreated, but through hard work, strong families and religious faith, they triumphed over obstacles and achieved the American Dream.

That narrative, though true in its broad outlines, is too simplistic. As Vaccara and others, such as the Sicilian historian Salvatore Lupo, in his History of the Mafia, have established, Sicilian immigration to New Orleans also brought the Mafia to America. Sicilians began immigrating to New Orleans in 1860, and by the end of the nineteenth century, the city had the largest Sicilian colony in the United States. The immigrants were drawn by the climate, similar to Sicily’s, but more so by work, in agriculture and the lucrative and expanding business in produce. Fruit and vegetable exports from Palermo began to rise in 1850, and New Orleans became one of the most important destinations for that produce. “The lucrative business of fruits and vegetables in the expanding world market…was a magnet for the Mafia,” Vaccara notes.

New Orleans became “the ideal marketplace for the Mafia from the mid-1800s” also because the disorganized and corrupt city administration provided a favorable business climate for organized crime.

Carlos Marcello, born Calogero Minacori

By the time Carlos Marcello became the leader of the New Orleans Mafia in the late 1940s, Cosa Nostra had been a thriving enterprise for decades. It flourished there largely because, “In the Big Easy, more than in any other American city, the top politicians and civil servants learned how to share power and profits with the bosses of the oldest Mafia family in the United States.”

(Speaking of that fabled city and its Mafia history, the good news is that Carlos Marcello’s crime empire no longer exists. In today’s New Orleans there are no Mafia “families” to speak of, and the FBI no longer maintains an organized crime squad in the city. Carlos Marcello’s descendants still live in the area, but none of them went into the family business.)

Carlos Marcello: The Man Behind the JFK Assassination hopefully will enlighten readers about the Mafia conspiracy that killed a president, or at the very least, make them question the conclusions of the Warren Commission, whose work Robert Kennedy Jr. recently described as “a shoddy investigation.” And if the director David O. Russell does indeed make a film from the Waldron-Hartmann book, Legacy of Secrecy, as he has announced, the Marcello-Kennedy connection no doubt will become more widely known and discussed.

Stefano Vaccara’s book of course cannot answer all the questions surrounding the assassination. As he acknowledges, he has not found a “smoking gun” that would definitively tie Marcello to Kennedy’s murder, and some of his points necessarily are speculative. (Marcello may also have had a hand in the assassinations of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King.) But now, a half-century after the political murder in Dallas that stunned the world, the claim that “The Little Man” played the key role in that momentous crime cannot be dismissed as a mere “conspiracy theory.”

This is a version of the speech George De Stefano gave last month at Casa Italiana Zerilli Marimò of New York University in occasion of Stefano Vaccara’s book presentation.

*George de Stefano: journalist, critic, and author: An Offer We Can’t Refuse: The Mafia in the Mind of America (Faber & Faber/Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 2007).

*George de Stefano: journalist, critic, and author: An Offer We Can’t Refuse: The Mafia in the Mind of America (Faber & Faber/Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 2007).