My first memory of Giandomenico Picco goes back to about 15 years ago, when I was working on a documentary that I was producing, “Why is Kofi Annan Not a Woman?” – an in-depth analysis on gender equality within the UN leadership. My wish was that, heading towards the end of the UN secretary general’s term, there would finally be a woman on the 38th floor of the United Nations. Things went differently.

However, Picco’s words during that experience remained impressed in my mind, of how his experiences as a negotiator in all four corners of the planet permitted him to get to know many of the female protagonists of an untiring diplomacy, often less palpable and immediate with respect to male colleagues, but undoubtedly of crucial importance within the intertwining of balance that governs international relations.

I remember how, addressing them specifically, the former UN under-secretary general was said to be poised to think “outside the box”; or rather, to go outside the parameters of conventionality, because in such manner he would seize the opportunities which certain prejudicial mechanisms prevented them any access to. A calm message, apparently surly, but in reality, steeped in the typical peremptoriness of the Friulian DOC from Udine.

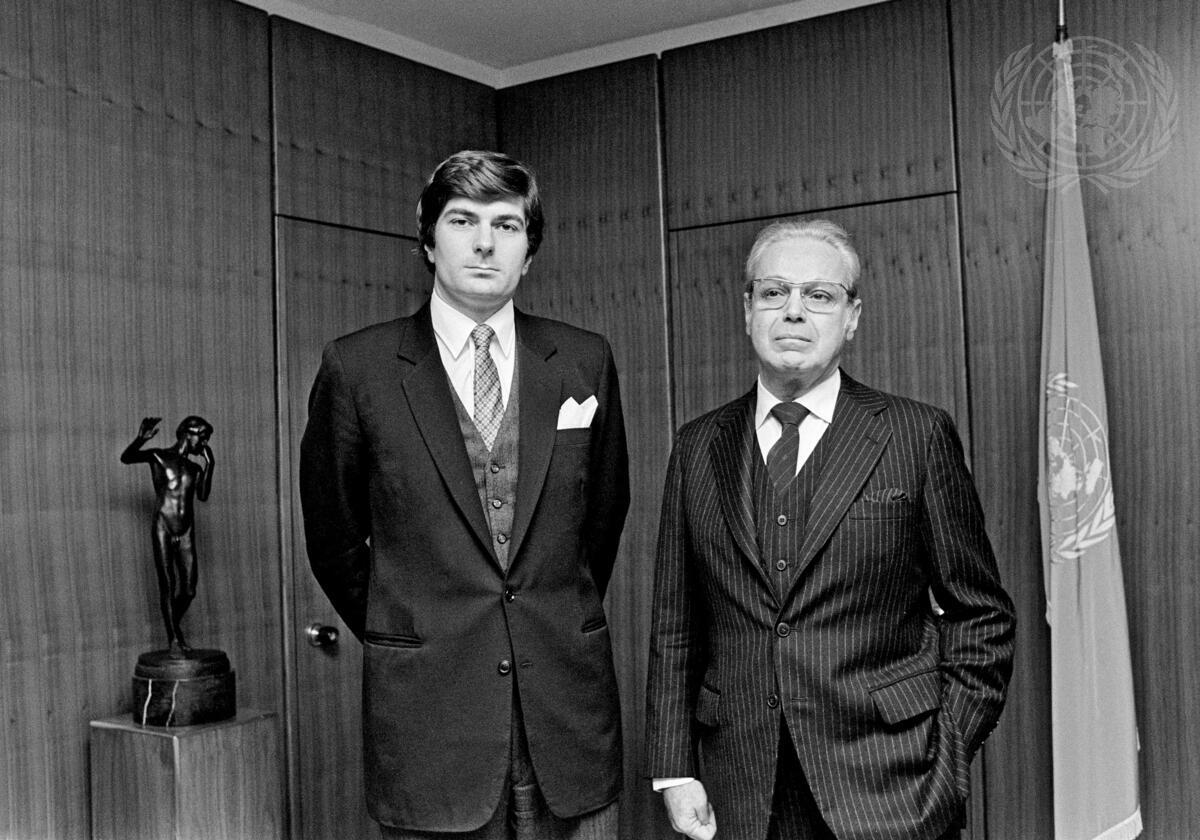

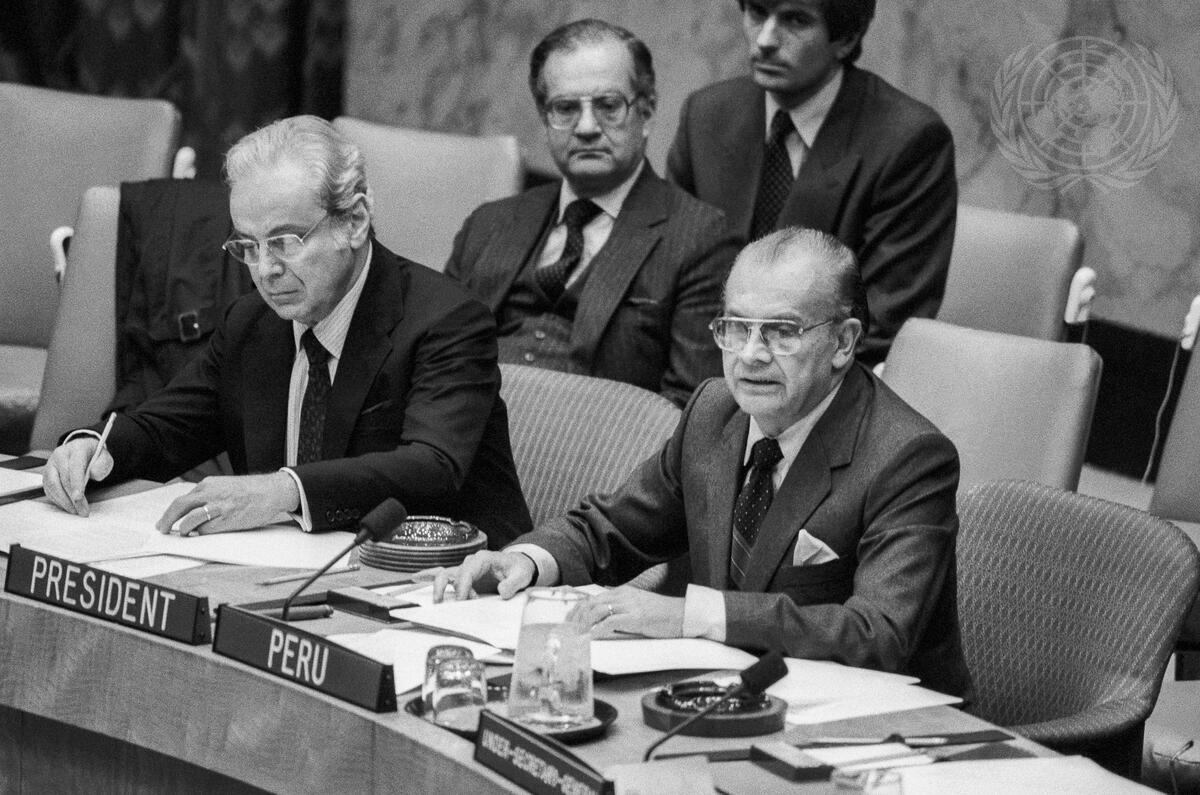

The impression that I had confirmed the image of him that I had created; a man preceded by his formidable professional history as an “unarmed soldier of diplomacy”, as former Secretary General Javier Pérez de Cuéllar defined him, and how books, newspapers and older colleagues refer to him. A profile that raised in me an instinctive curiosity from when I first started covering international news, and which perhaps contributed to the development of my fatal attraction for high-risk regions.

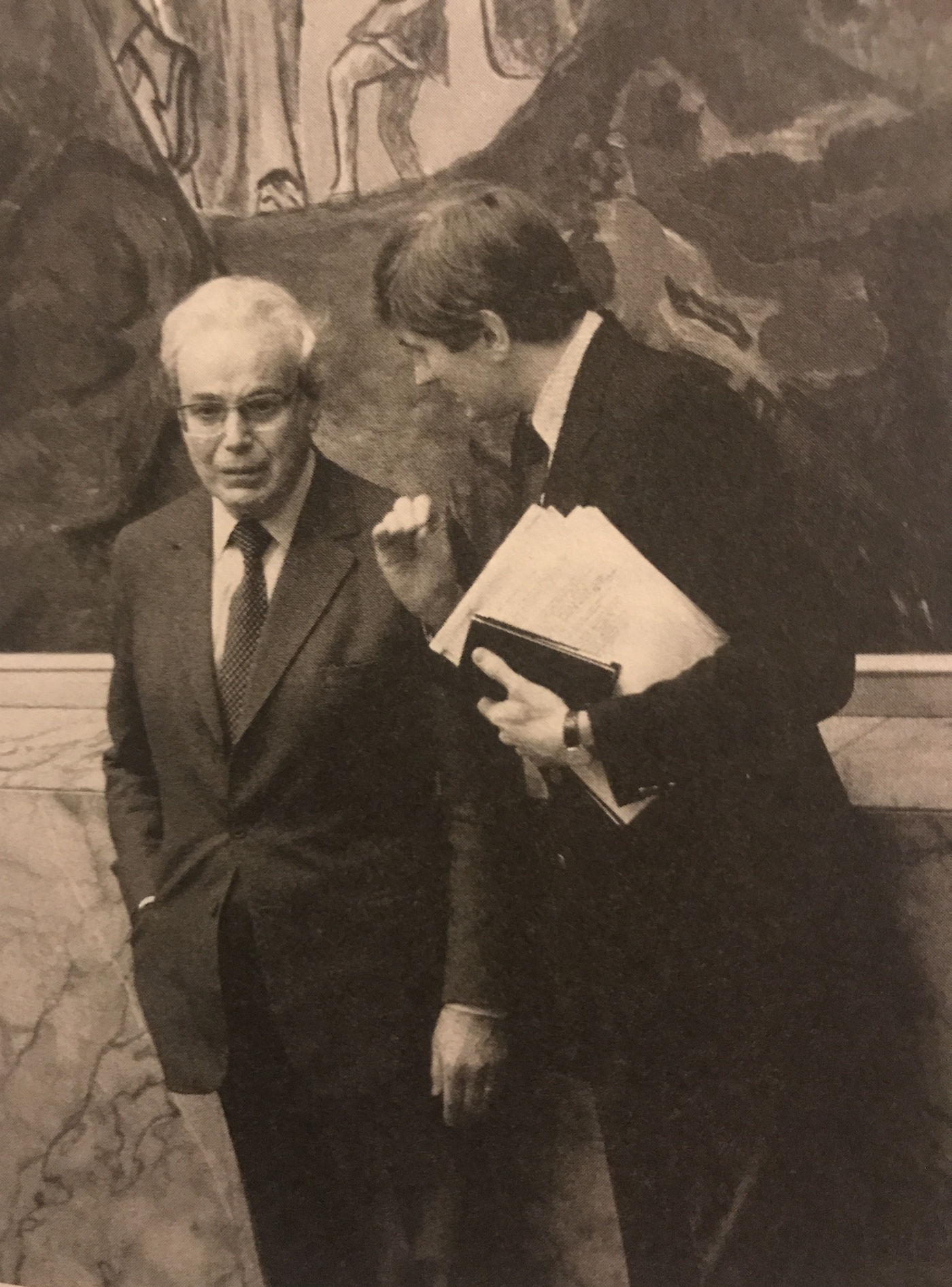

“To make a long story short”, as the Americans say, we can retrace some fundamental steps of Giandomenico Picco’s long career, leaving aside his full résumé and the review of all of the honors that he has collected in over thirty years. Picco served at the United Nations for over thirty years in the field of Conflict Resolution, reaching the level of Under-Secretary-General. He was personally and directly on the front line in the negotiations that brought an end to the Soviet invasion in Afghanistan in 1988 and of the Iran-Iraq war of the same year, and he participated in important peacekeeping missions in the Balkans.

But the most renowned chapter of his experience was in UN negotiations from 1989 to 1992, for the release of Western prisoners in Libya–captured by guerrillas that would evolve into Hezbollah–just as he spent years bringing home other missing or imprisoned people who were not given due process.

The Shiite militias had been the protagonists of a long series of abductions: in those years 104 people disappeared, of whom 26 were American, 16 French, and 12 English, just to name a few. On September 11, 1985, on his birthday, the militias also abducted the Italian national Alberto Molinari, vice president of the Chamber of Commerce in Beirut. That “he was never found,” is Picco’s biggest regret. Among others, there was also the English Anglican, Reverend Terry Waite, who tried to negotiate an agreement, and the AP journalist Terry Anderson, kidnapped on March 16, 1985 and, following the longest period of captivity, was released on December 4, 1991.

CIA station chief, William Buckley, kidnapped in March 1984, was tortured and sentenced to death — or died of a heart attack — in front of his executioner, while the Marine Colonel Higgins, was hanged. The terrorists threw the bodies of both Americans into the trash, a vile warning.

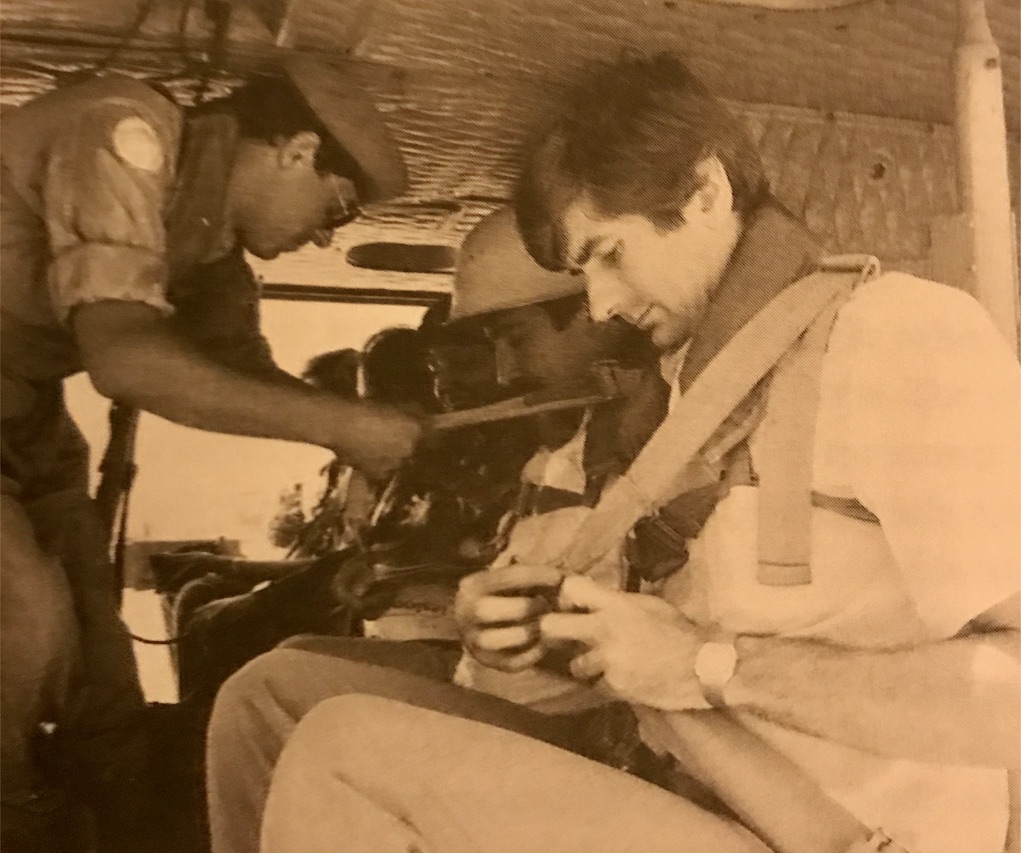

So many, too many. In this way, the envoy Picco, conscious of the ties that existed between the Shiite militias and the Ayatollahs’ Iran, revived some old American friendships, such as that of the present-day head of diplomacy in Teheran, Javad Zarif, whom he had met while he was studying in the US. They were the key to at least attempt a negotiation. He received the green light from Pérez de Cuéllar, and the rest was due to the courage of a front-line diplomat — who with a hooded face, curled up in the trunk of a smashed-up Mercedes — reached the torturers with a lump in his throat and fear in his stomach, “thinking of my wife and son that I feared never to see again.” One trip after another, until able to negotiate with the boss of the bosses, he finally convinced him.

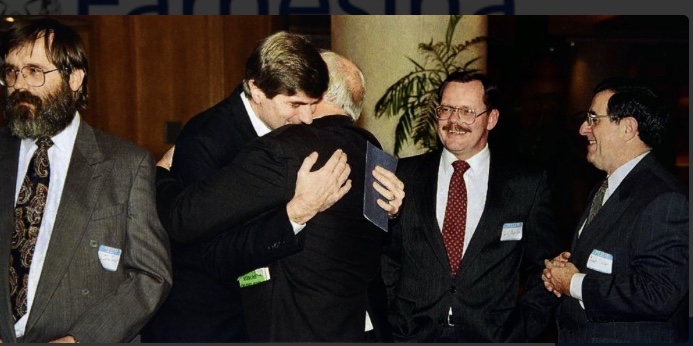

The last ones to be freed from the dungeons of a Beirut devastated by three decades of war, were the German volunteers, Thomas Kemptner and Heinrich Struebig, who had been kidnapped in 1989 and were released on June 17, 1992. “Those were my best days,” Picco would later write in in his book, Man Without a Gun. One Diplomat’s Secret Struggle to Free the Hostages, Fight Terrorism, and End a War. A man without a gun, but with the heart and courage of a bigger caliber, as testified by the moral and material honors of the countries involved in the release: “President George H. W. Bush offered me American citizenship; I politely declined.” The epilogue of Picco’s professional life is however, written in his DNA. The under-secretary clashed with the jealousy of certain UN technocrats, skeptical of “disarmed diplomacy”, so he decided to leave the United Nations.

The privilege that I take with me, as an extraordinary cultural baggage, is to have spoken directly with him about all of these things when I used to call him at his GDP Associates offices, the company of strategic consultancy that he opened in 1994 — sometimes in the course of interviews, other times in just small talk during which time I tried to understand some of the behind-the-scenes stories that hadn’t yet been told. Just like the ones that took place five years ago, coinciding with a mission of mine right in Lebanon, to interview some exponents of Hezbollah regarding their involvement in the Syrian conflict against Al Nusra and the Islamic State.

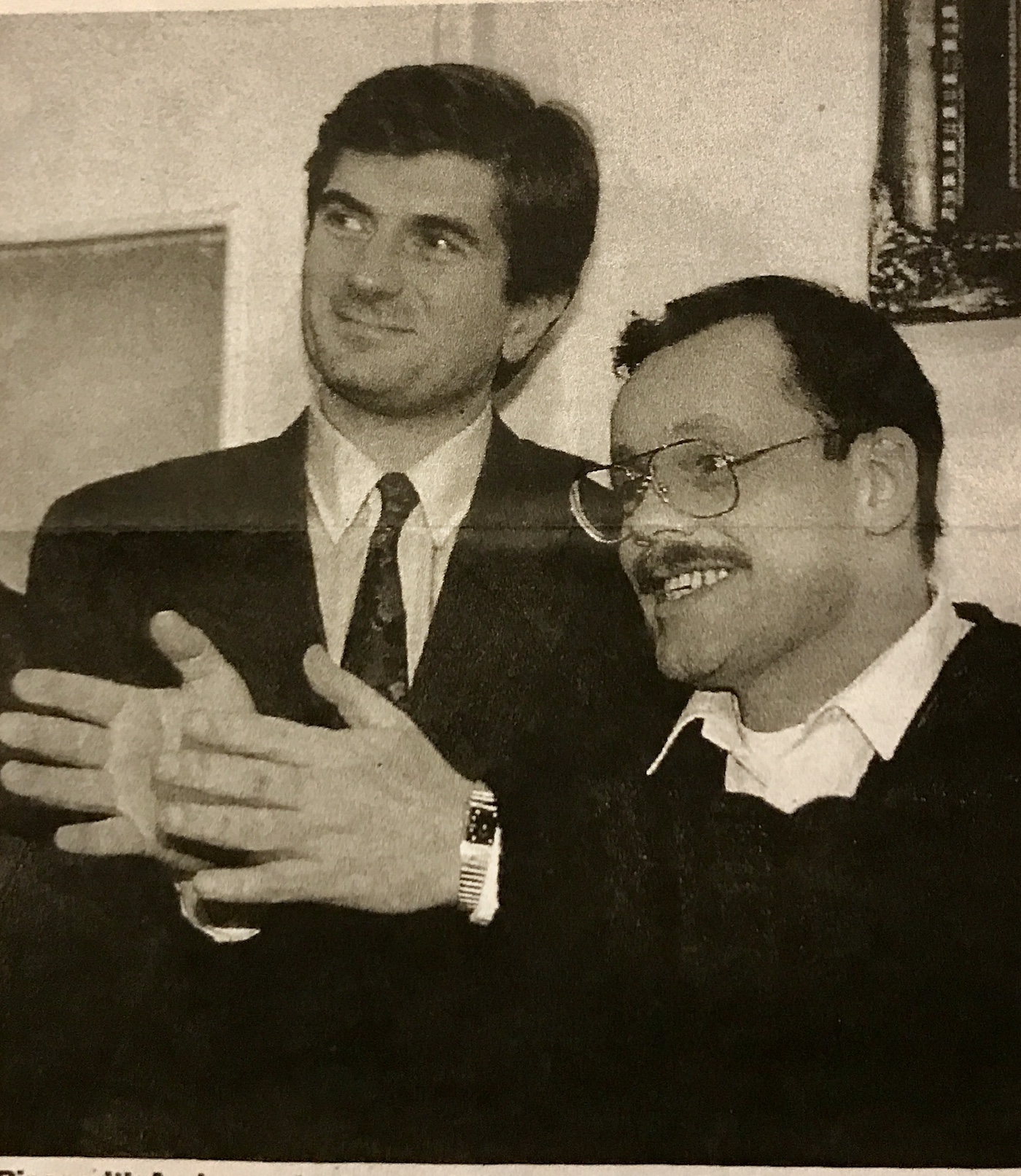

“The party of God”, a direct descendent of the militants that Picco met during his long, tenebrous nights amongst the rubble of Beirut. During that time — it was in 2015 — we were organizing the presentation of a book with the United Nations Correspondents Association, Il Califfato del terrore: Perché lo Stato Islamico minaccia l’Occidente (“The Caliphate of Terror: Why the Islamic State Threatens the West”) by Maurizio Molinari. It was actually Maurizio that insisted on having Picco on the panel, so as to transform the presentation into a conversation with the former Under-Secretary-General and understand what had changed from his wars to the new war on terror that dominated the regional and international scenes. An appointment preceded by a few cups of coffee in front of the UN, where Picco would arrive in his impeccable grey double-breasted suit, black umbrella and blue passport in pocket (“in case they don’t want to let me enter this building”), and phone calls, even at the oddest of hours, in which he would retrace the past and interrogate himself on the future.

One of his obsessions had always been the symbolism of the number 8; he wrote to me about it in an email he sent to me following a quarrel he had had with a publishing house over the use of the date 8.8.88, begging me to be rigorous in the writing of the biography that we would use to present him at the UNCA: “The key to my life is the number 8” he still repeats like a mantra on his social profile – “I was born on October 8, 1948, and mediated the cease fire in the Iran-Iraq War, after eight years of war on 8.8.1988 and at the end of the 1980’s, I began negotiations for the release of Western hostages.”

Nemesis following secular questioning, such as when he is asked about what the Old Continent should expect as it faces the sunset of the nation-state reality, and about the difficulties to emerge of a macro-regional “Europe”. Discussions were tackled before and after that long conference where Giandomenico Picco offered his take on the issue, sometimes going beyond the peremptory calmness of the Friulian DOC from Udine, betraying the matured mistrust for an institution that he no longer felt as his, and also demonstrating a bit of physical fatigue.

From there followed other encounters where skepticism and fatigue slowly took over. Gianni Riotta, in a profile interview of Picco in 2017, concluded it with a milestone question: “Would your daring courage work with ISIS, with jihadists that are detaining the Jesuit priest Dall’Olio and the businessman Sergio Zanotti?”. “My world was simpler, the US and USSR were in command”, replied Picco. “Now, it’s a jungle. I went when everyone would say to me, ‘Make a career for yourself, why in God’s name are you doing this?’, because they didn’t believe that a UN diplomat could be equidistant between terror and tolerance. I paid high prices, publicly and personally, for my choices.”

“You’re proud when you talk about the nights in Beirut, 25 years ago”, comments Riotta. Picco’s look becomes darker, “Because it’s tough, it’s lonely, and without pay, the job of a hero,” he himself confesses. But it’s a job that leaves indelible memories, unconditioned, from which everyone — no one excluded – have drawn a human, cultural and political teaching, I must add. And now that it is Giandomenico Picco – the man, even more than the negotiator-to be in need, it is precisely memory that must come to his aid.

ALL IT TAKES IS JUST A CLICK, A TOUCH (HERE BELOW) TO ACTIVATE IN ALL OF US A LITTLE PIECE OF THAT GENEROUS MEMORY.

To make a Go Fund Me donation:

http://gf.me/u/y8bwpm

To visit Giandomenico Picco’s TikTok profile page:

https://vm.tiktok.com/ZMJgHn1Gp/

Translated by Emmelina De Feo