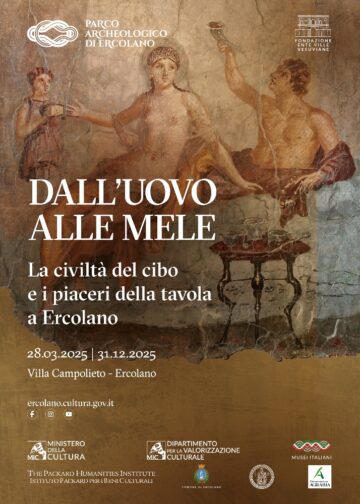

The exhibition, “From Eggs to Apples: The Culture of Food and the Pleasures of the Table in Ancient Herculaneum” will be on display in the Campanian city of Herculaneum until December 31.

Located at the magnificently frescoed 18th-century Rococo Villa Campolieto designed by the Neapolitan architect and painter Luigi Vanvitelli (1700-1773), it’s the first exhibition devoted entirely to ancient “Roman” food. Its title comes from a proverb: “ab ovo usque ad mala” by the ancient Roman poet Horace, who was alluding to the Roman tradition of starting a meal with eggs and finishing it with apples.

The first of the exhibition’s four sections, “Daily Bread,” concerns ancient Herculaneum’s most important food. The bread displayed here was made with many different grains: spelt, millet, barley, and wheat for examples, and in many different forms as it still is today: round loaves or flat like today’s pizza. At first the grains were home-ground and home-baked. Later, bakeries produced both bread and cakes. Also on display here are millstones, primitive hand-turned mixers, and bronze baking dishes and trays.

On display in “Not to Bake, to Cook” are legumes: lentils, chickpeas, dried peas and beans, the common ingredients for thick soups, very popular nourishment in Herculaneum during the autumn and winter, as well as numerous terracotta pots. Iron spits and grills for cooking meats–usually chicken, pork, rabbit or lamb– as well as bronze utensils are also featured.

There are four highlights: a covered bronze boiler omnipresent on a stove so there would always be hot water available to add to “slow-cooking” dishes like soups and brazed meats; a large decorated bronze “barrel” or cista always filled with water for household use not only in the kitchen. A multi-shelved wooden cupboard excavated in a store still contained amphoras full of olive oil and wines, sacks of flour, onions, dried vegetables, pinenuts, almonds, dates from Egypt, and terracotta or glass jars of honey and valuable spices, here pepper from India.

The highlights of “Shopping List” are two frescoes on loan from the National Museum of Archaeology in Naples: one of mullets and shellfish and the other of amphoras labelled with the local wines for sale, hand-held scales, coins, and a locellus or wallet made of wood, bronze and silver. Those in “From Breakfast to Dinner” are the different tableware and food samples at the three daily meals: Ientaculum, Prandium, and Coena and a larva convivialis, a banquet’s table decoration of a miniature silver skeleton to remind the guests, usually both men and women, that life is short so enjoy its pleasures.

Herculaneum is some 10 miles north of the Pompei. Both towns were destroyed in 79 AD, one day apart by the same volcanic eruption. The only surviving eyewitness account are two letters written by Pliny the Younger, a Roman lawyer, magistrate and author and sent to the historian Tacitus some 25 years after the disaster. Today their surviving six pages are conserved in the Morgan Library in New York City.

Pliny describes how on the first day Mount Vesuvius erupted ejecting a dense cloud of ashes which totally blackened the sky before it buried the town of Pompei suffocating its inhabitants and its weight collapsing the buildings. Instead, he explains, very little ash fell on nearby Herculaneum, allowing almost all of its inhabitants to escape before the town was buried under lava which flowed down the mountainside the next day. Once the lava solidified, this rich town, a seaside retreat for the Roman elite, was preserved charred, but nearly intact, sealed without oxygen, sort of like sous vide.

Pliny doesn’t indicate a date, so for many centuries it was believed that Mount Vesuvius had erupted during the summer. However, recent excavation and research have shown that the eruption took place on or after October 17 for several reasons. The Pompeians were wearing heavier clothing than their light summer clothes. Coins found in a woman’s purse there include one with a 15th Imperatorial acclamation among the Emperor Titus’s titles so couldn’t have been minted before the second week of September.

In addition, wine fermenting jars, excavated in both towns and a few of which are on display here, had been tightly sealed, which would have happened around the end of October. Not to omit that the fresh fruits and vegetable excavated in Herculaneum’s shops, some of which are on display here, although carbonized, are typical of October and conversely the fruits typical of August were already being sold in dried or conserved form.