There’s a famous Italian tale about the beautiful windows that adorn houses all around Liguria. In the olden days, windows were more than just a functional tool for they also symbolized wealth. A small family living near the seaside would have to pay a tax for each window that was constructed on the home, and so the more windows you had, the more pronounced your financial status.

It is therefore quite curious that most families actually painted windows onto their houses — it allowed them to enjoy the illusion of wealth, and also skip the tax bill. “I don’t know the English term for this kind of person,” Andre said as we stood in front of a house, examining the windows. “Cheap,” I responded with a grin. “Yes, but this is only famous of Liguria,” he reassured me, “and it was many, many years ago.”

Photo © Joan Erakit

I had spent the better part of two days riding bikes around Albenga with Andre, taking in the lush green mountains, the deep blue skies and an ocean that seized to keep still. At night, if lucky, one could even hear it speak against your skin in a cool monotone.

I met Andre a few months back at the Raffaela de Chirico Gallery in Torino while taking in work by a local Iranian artist named Moshen Baghenejad. A friend of a friend, he had agreed to give me a mini-tour of the area before meeting up with our group at the beach later that day. For this American girl, he was your typical Italian man: charming, handsome, elegant and just a tad mysterious.

I enjoyed his stories, his ability to find goodness in every corner of life, and most of all, his appreciation for his country. Andre carried around what I could only describe as a sense of nostalgia — he understood the past so clearly, enjoyed the present and made no commitments to the future. In this regard, he was the perfect person to teach me about Liguria.

For Americans, Italy is the land of wine, food, fashion and romance (I am of course guilty of overindulging in each category since my arrival) so it only makes sense that as a writer, I would desire to learn more.

At the age of 32, I have taken two vacations in total. One when I was 23 (Puerto Rico with a musician friend for five days) and another when I was 30 (a beautiful trip to Barbados to visit a friend I met on Instagram).

My life, like most Americans, has always been consumed by work. In a 40 hour week, many of us have been logging in 60 – 80 plus hours of extra grinding, so it’s no surprise that unlike our Italian counterparts, we are not so adept to the art of holidaying.

Once I arrived in Italy, I was told about the famous month of August for which all Torinese disappear to the seaside or the mountains. The history is derived from the old Fiat days for when factory workers, most of them from the south of Italy, would return to Palermo, to Naples or other areas to recharge for a month.

“Joan, Turin is empty in the summer months, so we’ll go to the seaside,” my friend Elisa told me over drinks in early April.

Being the woman-about-town that she is, Elisa had quickly planned an entire summer for us filled activities, friends, family and lots of prosecco.

This past weekend, I got a little taste.

Photo © Joan Erakit

We left Turin around 4pm on Friday to beat traffic and head to Albenga — or better known as the Italian Riviera as it is penned on many roadside billboards. In our particular social circle, we have the tendency to roll deep — at least eight to ten people in one setting — a situation that would cause a well meaning hostess or bartender to panic.

It’s a part of Italian culture untouched by the chaos of divisive politics, a complicated economy, or a uncertainty of what lies ahead. In some ways, watching people flock to the seaside reminded me of many New Yorkers who went to church on Sunday in search of respite before the week.

Italians do their seaside holidays religiously and I am absolutely here for it.

*****

Elisa drives like a boss.

A trip that should take two hours, she makes in about an hour and 10 minutes. We skip the highway and take a side road that leads us through the mountains that separate Piedmont and Liguria. The tiny two-lane road is something out of an old French film — one never knows when oncoming traffic is approaching, or if the driver will lose control and send the car over the cliff.

Once in Albenga, we head to the beach for a bottle of wine at a local bar perched on the rocks called B-Side. As we wait for our friend Val Moro, we sit silently taking in the salty smelling air, each lost in a myriad of her own thoughts.

Many of our friends will be arriving soon and a huge dinner will take place at home, prepared by Elisa’s doting father who has generously allowed us to stay at his home.

I observe the people around us; families, singles, couples, dogs — one woman even has a cat in a basket as she sips a beer to the sounds of Tribe Called Quest.

Everyone seems so far removed from the hectic life they lead elsewhere. Whilst I’m curious about their backgrounds, their day to day lives, I am also astonished at calmness that I feel.

It’s not easy for me to relax, I often feel that my leisurely time should be used productively — for this reason, I’m never without a book, a pen or a pad. Being in Italy has forced me to resolves these issues and just do nothing.

****

Having done nothing, eaten well, enjoyed a beautiful wine and fallen in and out of sleep, I awake the next morning to the sounds of an espresso machine in the nearby kitchen. We have been a house full of different people from different backgrounds.

I chuckle to myself when I realize that the American in me feels a little lost surrounded by so many different people. We like to think in New York that we are the most comfortable in these settings — and we are — just as long as all that different-ness doesn’t happen in our own backyards.

I’m baffled by the sense of intimacy I feel among people I haven’t known for so long. A few minutes later, I brush my teeth as someone walks into the bathroom to ask me a question about what I want to do later. I respond and realize that I am only wearing a bra and pair of shorts. At this moment I feel naked, but also very free to be among people who seem to carry no judgment, therefore allowing me to be myself.

We leave the house as a group. Andre and I take the bikes, others take cars, each on a mission to enjoy the sun, the sea, and privileges of carefree living.

Photos © Joan Erakit

Essaouira is popular lounge and beachfront club in Albenga that operates at the utmost efficiency, professionalism, and fun. With all the tiny bikinis, endless bottles of prosecco, delicious plates of fresh food and DJs who spin the most incredible mixes this side of Italy — for this American girl, it’s Miami Beach done the Italian way.

Andrea, one of the head bartenders behind the bar indulges me by making the best Bloody Mary I have had in Italy. Using his very own special recipe, he chides me about the importance of spice, while dousing Tabasco into the cocktail mix. I look around the room feeling that there is no other place I’d rather be and am instantly grateful for friends who have ultimately become my Italian family.

Seven months ago, I was completely alone trying to figure out what it was I would write about and why. I felt it difficult to make friends and in reality, worried that my American background would not mesh with this new Italian landscape. Seven months later, in a house (and beach club) full of people, it would be a miracle if I had a moment alone.

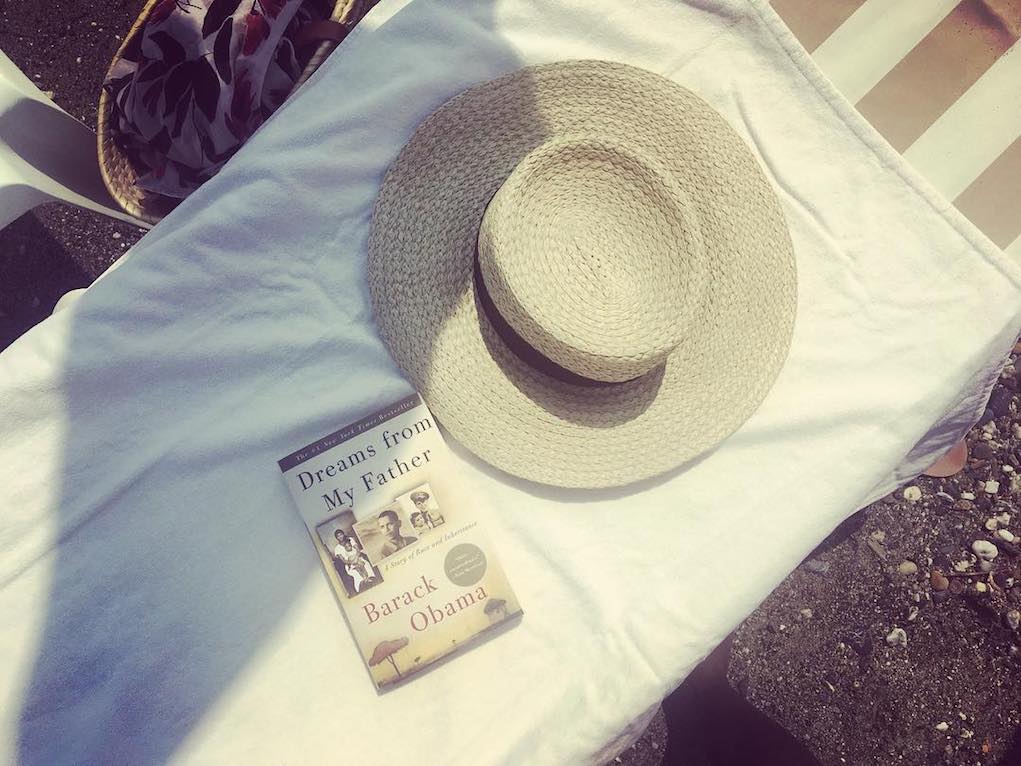

And maybe that’s the thing about the Italian holiday: it’s not only time dedicated to reconnecting with yourself, but with others. Later, while laying on a beach chair reading Barack Obama’s Dreams of my Father, I witness an unexpected interaction between Elisa’s mother and a well-known migrant street vendor from Senegal named Nini. He has the demeanor of a village chief and when we first me, he called “my child”.

He does in fact remind me of the elders I knew when I was growing up in South Africa and I have come to find that I search for him whenever we are on the beach.

Elisa’s mother invites him to take a seat on the beach chair near her while she carefully examines the goods he is selling, chatting with the familiarity of an old friend. He is engaged, half smiling and speaking Italian as a little girl runs towards the tide. In this particular moment, I realize that he too has escaped his daily need to survive.

Both mama and Nini look out into the ocean for a few seconds admiring some sort of Ligurian dream.

The scene is a reminder that none of us is immune to escapism, and until we figure out solutions to our problems, we will escape the city and continue to recharge at sea.

Just as the Italians do.