We have a saying in my father’s village: “the way you were born is the way you will live your life.”

I was born during a coup in July of 1985 and my parents were escaping in the dead of night, thanks to an American missionary who would later become my adopted grandfather. My mother often recalls this story while sorting the laundry saying, “He drove like a madman. I didn’t know whether my contractions were because you were ready to come out, or because he was turning corners like a race car driver.”

Crossing the border between Uganda and Kenya, I was born in the town of Kisumu on the morning of the 29th — a pit stop for my traveling parents and their American friend Charles. I have managed to live my 33 years of life on a plane, a train, or in a fast car — always in search of a home I never quite knew.

When I touched down in Tel Aviv last October, I was restless with the feeling of a wanderer. I didn’t know what “home” would feel like and I was reluctant to search for it. Before arriving, a close friend turned brother-from-another-mother, Dror, had offered a room in his house as a place of refuge for a few weeks while I worked on my book. He and his beautiful wife Yuli lived with their children, a charming dog named Pumba and a collection of stray cats in Mevaseret, a suburb of Jerusalem. For a little over five weeks, Dror and Yuli’s home became a much-needed sanctuary for me.

I joined the family meals — one of my favorite pastimes — I let the dog out in the mornings, I took walks around the neighborhood, I sat on the couch with a tea while family friends came over. On Friday’s I ate Shabbat dinner with the grandparents, I unloaded the dishwasher, I read from the terrace in the afternoons, and on Saturday nights after partying with friends in Jerusalem, I tip-toed up the stairs to my bedroom as not to wake anyone.

It felt like family, and it felt like home.

Joan and Pumba in Mevaseret. CREDIT: Joan Erakit

For the days that I struggled to write, missed my own family back in the States or worried about my future, Dror would arrive home with a bottle of wine, a few wise words and a chuckle. He never missed an opportunity to course correct my thinking. Yuli would give me a hug and insist that I drink more water on those days — the things only a mother could do. On the weekends after dinner, we’d descend downstairs and watch Game of Thrones with the dog at our feet — me squealing through the gory bits.

Dror and Yuli had become the anchor in a city many found foreign, a blessing I could only wish for others.

****

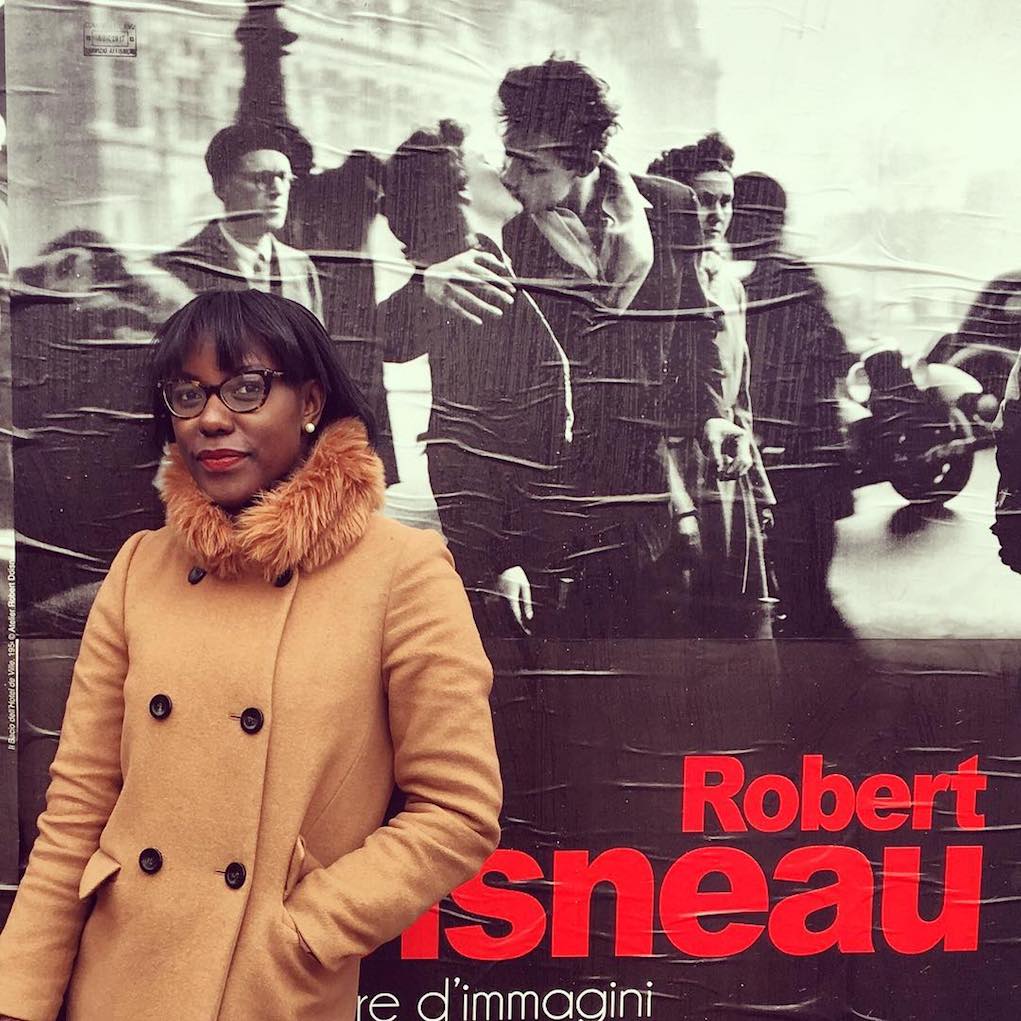

“Home is wherever you are,” is a saying I used to whisper to myself when I first lived in Paris. It did not escape me then that a curious french woman (and my neighbor) used to ask: “Why do you move around so much? What are you looking for? Why don’t you just settle in one place?”

I never had any answers to her questions, and I doubt I ever will.

What I have come to understand is that home and family don’t always look the way you expect them to.

In Teju Cole’s essay Home, Strange Home the writer recalls his journey from Lagos to Kalamazoo, Michigan to attend college after years of growing up in Nigeria. Throughout the essay, you sense his conflict — he struggles to embrace the new while feeling like he’s losing an important past. He writes:

“The Journey to Kalamazoo seemed like a journey of return,, the opposite of exile. A direct flight from Lagos to JFK, followed by a day-long train journey across the Midwest, had brought me to the town where my parents were married, the town where I was born and baptized. I had no anxiety about legal documents. Picking up my Social Security card was an afternoon’s errand. I got a job at McDonald’s, and banks gladly loaned me money for college. But, my first evening on campus, as I wandered around in what seemed like intolerable cold, it suddenly struck me that everyone I loved on this earth was almost six thousand miles away. I was flooded with panic, like a young boy in a helicopter being pulled away from all he’d ever known. Seventeen-years of invented memories abandoned me. A sob ascended my spinal cord. That evening, I began to invent new memories for myself. These new memories were all about the home I had left to come back home: what I had liked about that other life, and what part of it I was happy to be rid of.”

When I first arrived in Italy, I stayed with Gaetano and Mariella, a wonderful couple who were so kind as to look after me as I found my footing. Like Cole, I struggled with letting go of the home I had come to love — New York — and tried to invent new memories to get me through the hardest days. It’s possible that the bitter cold of Turin added to the sense of loss and confusion I faced that first month and a half, and during my stay, I suffered the anguish of the masked depression one feels when separated from their home.

For those days, I would hide my sadness by washing more dishes or gushing over a delicious meal that Gaetano had prepared. I would return to my room with a book pretending to write, just so I could cry. Later, I began to understand that it is harder to move to a new country as an adult for you are set in your ways, in your habits, and in your perceptions. There is a reason people my age and older don’t like to start afresh — be it jobs, relationships, or even friendships. Change, regardless of background, becomes a challenge for which many of us are not prepared.

Like parents always do, Gaetano and Mariella somehow sensed my anxiousness and for that, Gaetano always had an exceptional idea to take a walk in the center of town, or explore the rolling hills of Langhe with a late afternoon drive. During lunch, after we had cooked together and set the table for three, he would amuse me with stories of he and Mariella’s first meeting and their road trips on motorbike. He would talk of the love they both shared for their two girls and of the hopes for the future. From Gaetano, I learned that the meaning of “Home” was only relative to those around you.

****

About two months ago, I was transitioning from one apartment to another, and in an effort to save money and get situated, my friend Elisa offered her second bedroom for a month. Prior to that, Liam, another good friend had allowed me to stay at his home while he was away for work and holiday. The constant in my life has been the generosity of others, and still to this day, I am amazed at the humanity displayed in the selfless act of giving someone a home.

One night, at my extreme lowest, I was seated cross-legged on Elisa’s kitchen floor, nursing a glass of wine and fighting back hot tears. I felt hopeless having battled through yet another professional drama and I also felt like a burden to my friend. Her response to my meltdown was both unapologetic, and sincere: “It’s friendship, Joan. My home is your home. You would do the same for me and so would your family,” she said taking a sip of her wine.

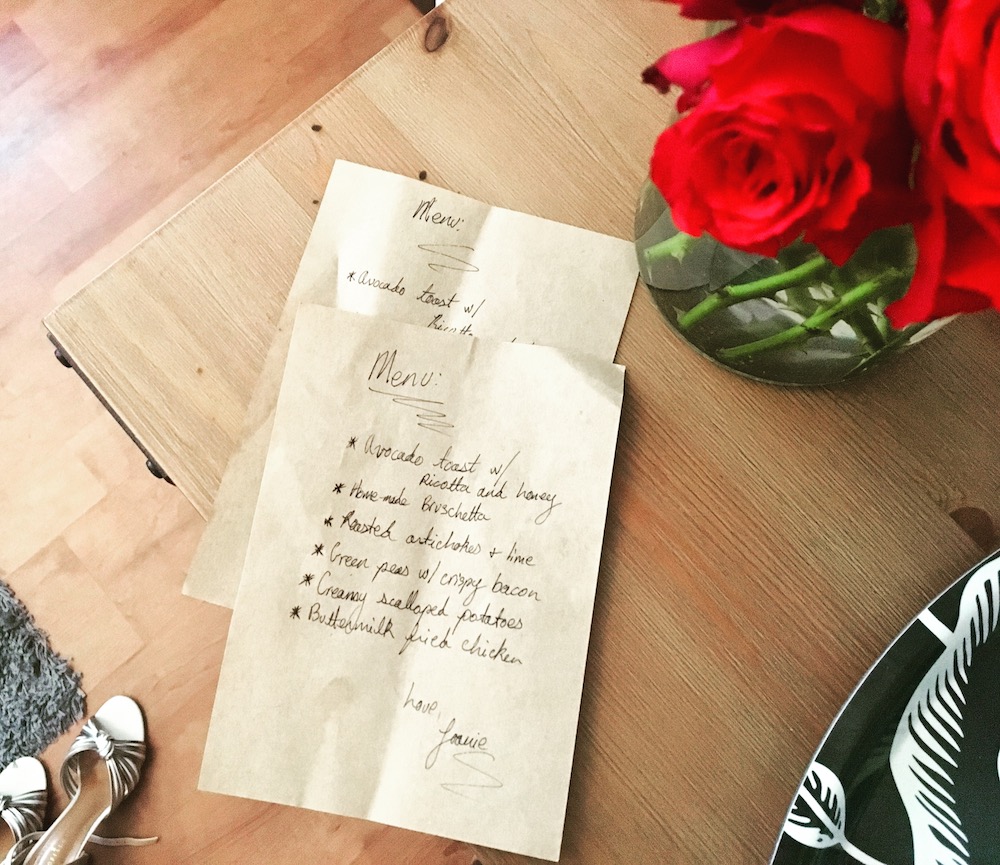

It’s been many days since that conversation and as I write this, I am seated in my bedroom with the windows open. Outside, my neighbor is parking his car and unloading groceries. His granddaughter skips along behind him as they cross the street. My new place in Turin has become home to many. It’s not uncommon to find a gaggle of my friends seated around my dining table, eating a meal I’ve cooked. Friends often drop by for a night-cap, heading downstairs to the bar and sitting wherever there is space. I want my home to be a home for all, in some ways, to live out Elisa’s wise words.

****

Webster’s definition of a migrant is, “one that migrates; a person who moves regularly in order to find work especially in harvesting crops.” A person who leaves their home in search of greener pastures. To work, to grow, to learn, to seek out better opportunities.

I am a migrant myself, as are many others who live in Italy today. Some of us are white and some of us are black. Some of us come from Cameroon, and some of us from Canada. Others from Iran, and some from across the border in Switzerland. Brasilians, Croatians and even Korean. Some of us studied French, others learned Spanish. Some prefer white wine from the South of Italy, and others a dark red from Piedmont. Some of us arrived by boat, others by plane. Some of us are rich, and some of us are poor — most of us work, while others study. Our search for greener pastures has led us all to Italy — some of us more privileged than others.

Sometimes on an off writing day, I stop near Porta Palazzo and take a coffee at the corner bar next to the number four tram line. I sit and watch a very particular old man work a stand selling second-hand clothes. He must be in this late 60’s. His skin has been bronzed from hours spent under the sun yet his eyes convey a sheepish demeanor that I am drawn to. He’s shy when approached –refusing to smile too much, aware of his missing tooth. I eavesdrop as he bargains with local women of all colors, shapes, and sizes coming to the conclusion that he speaks Arabic better than the speaks Italian, and he’s likely from Turkey — thanks to the tiny flag he keeps near some boxes of clothes. I wonder about his original home and I ask myself those heavy questions: When did he leave? Why did he leave? Did he come alone or with his family? Is he married and does he have children? Does he have grandchildren? Do they know that their grandpa works in a market and sells second-hand clothes? Did he go to school in his old country? Did he have a different job? Does he ever dream of going back home?

The questions fill both my mind and my writing pad. My coffee, running cold, is an indication that it’s time to walk back so I can get home. Later, when I go to sleep, I think of the old man in the market and wonder if he’s sleeping in his own home, somewhere in Turin.

****

In my search for home, I have lived with surrogate parents, adopted sisters and brothers, uncles and aunts who have gone out of their way to make me feel welcome. I am aware that not every migrant who has come to Italy has received this same welcome, nor will they in the future. I am reminded of something the Italian writer Gianluigi Ricuperati said to me over lunch one day: “Having a home gives one dignity. Above everything else, when you have a home, you can look someone in the eye.”

In order to honor the generosity, the kindness and compassion of people like Dror and Yuli, Gaetano and Mariella, Liam and Elisa, it is my daily task to be more understanding to those around me by simply caring about their lives. Through writing and teaching, I hope to do the most human thing possible: to restore the dignity so often lost when one is a migrant by simply welcoming them home, regardless of where they come from.