This week sees the observance of two anniversaries: the first, a global one, is the fiftieth anniversary of Martin Luther King’s assassination (April 4, 1968). Dr. King was a Baptist pastor and preacher, a civil rights advocate and activist who practiced non-violence and that in the last years of his life took a very strong position against the Vietnam war. The second anniversary marks fifteen years from the killing of Julio Anguita Parrado a few miles from Baghdad (April 7, 2003). Julio was a correspondent for the Spanish daily newspaper, El Mundo, in New York. The readers will forgive me this pairing, which can seem daring, and which is without any doubt very personal and subjective — but not without reason.

Exactly one year prior to his death, on April 4, 1967, Dr. King held one of his most important and controversial speeches in front of 3,000 people crowded into The Riverside Church in Harlem, New York, and after having established a logical and moral correlation between the defense of civil rights, and an absolute opposition to the Vietnam War, he reached the conclusion that “We still have a choice today: nonviolent coexistence or violent co-annihilation. We must move past indecision to action (…) We must find new ways to speak for peace in Vietnam and justice throughout the developing world, a world that borders on our doors”. He then suggested some practical measures to be taken, including an immediate “cease fire” and the withdrawal of all American troops. The major liberal newspapers that had supported him up until that moment turned their backs on him, President Johnson’s administration, that had also supported many of the requests of the civil rights movement, expressed doubts on King’s patriotism. And even many African-American associations judged his completely pacifist position as an inopportune one that would risk putting the still open issue of racial equality on the back burner.

If with his more famous speech — known as “I Have A Dream” (1963), he expressed a hope largely shared by the better America — with “Beyond Vietnam” (1967) he was accused of dividing not only the country, but even the progressive front and the very black community. However, as King himself stated in the opening of his speech, there comes a time when silence is a betrayal. And King spoke, but after 4 years, the dream had became a nightmare.

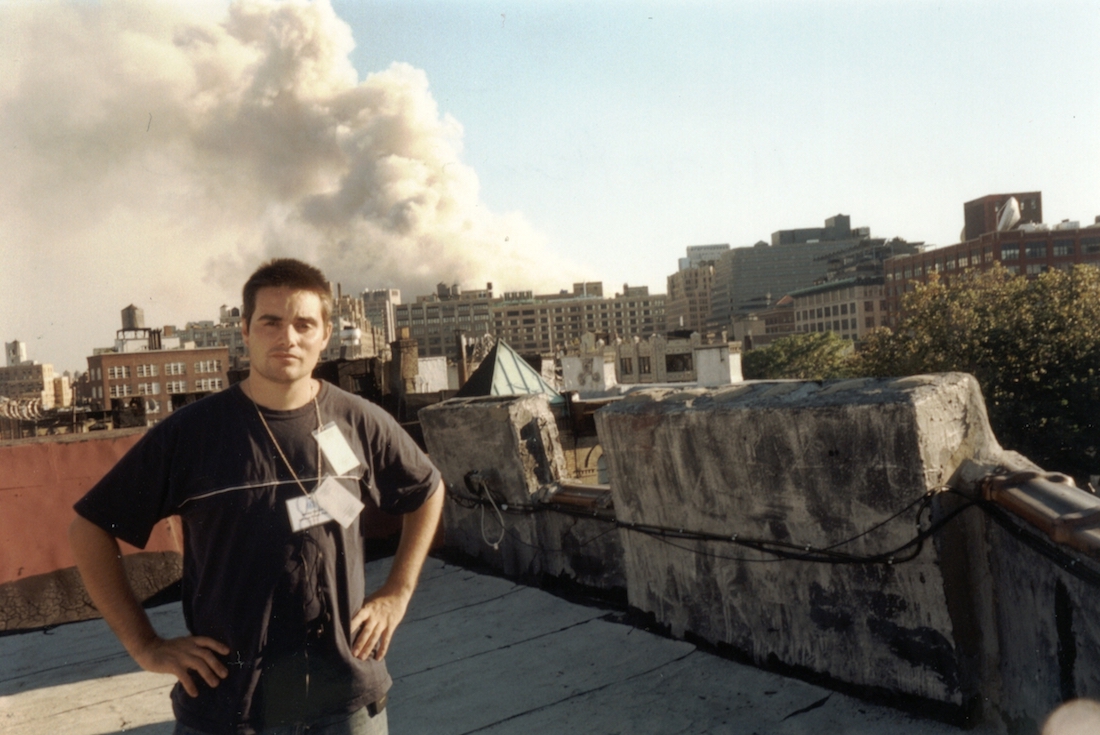

Julio was 32 years old, the last 6 of which we spent together in New York; he had requested a leave from the tenured job that he had at the newspaper’s central office and he had carved out a position as collaborator, just to be able to live in the city that with that frenetic pace and extraordinary energy seemed made just for him. Son of one of the most influential and respected political leaders of democratic Spain, Julio worked his way up and began signing his name purposely omitting his paternal last name because he wanted recognition solely based on his own merits. Our living room, from where I am writing in this moment, was his office. From these windows we watched the horror of September 11th unfold and I think that Julio was the first journalist in the world to break the news, before getting on his bicycle to run and see in person what had happened. He saw it and recounted it in his articles which, without taking anything away from an objective account, were a suffering elegy for a city that he loved so very much, shot through the heart, but ready to rise again.

Two years later, while George W. Bush was motivating the country to go to war with Iraq, Julio asked Spanish Foreign Minister, De Palacio three times during a press conference at the UN if she had seen with her own eyes proof of the existence of Weapons of Mass Destruction which had become the excuse for the war and which Secretary of State Powell stated he had shown to government allies (including Spain). And three times the Minister stalled, changed the topic and didn’t answer. We now know that she could not have seen any proof because they did not exist. Julio’s decision, as a pacifist and conscientious objector, to leave for the front line as an embedded journalist with the Third Infantry Division of the United States Army, upset me, but did not surprise me. If he had to recount a war, he wanted to be there, wanted to see it, hear it, smell it – he didn’t want to copy the agency dispatches or official army bulletins. For him, as with King, at a certain point silence became betrayal and he was not willing to betray his mission of truth.

Julio was killed exactly 15 years ago today, on April 7, 2003, a few miles outside of Baghdad. His story moved Spain, to which in the weeks prior he had recounted on the front page of his newspaper the absurdities and the daily occurrences of war. He was one of 150 journalists killed in that conflict, one of the hundreds of thousands of civilian and military victims of a war that, just like the one in Vietnam, left only losers. If America had more carefully reflected on that controversial speech by Martin Luther King, perhaps the subsequent wars would not have taken place and Julio, maybe, would still be running in the streets of New York with his bicycle to recount an America more just and inclusive than the present one.

Translated by Emmelina De Feo