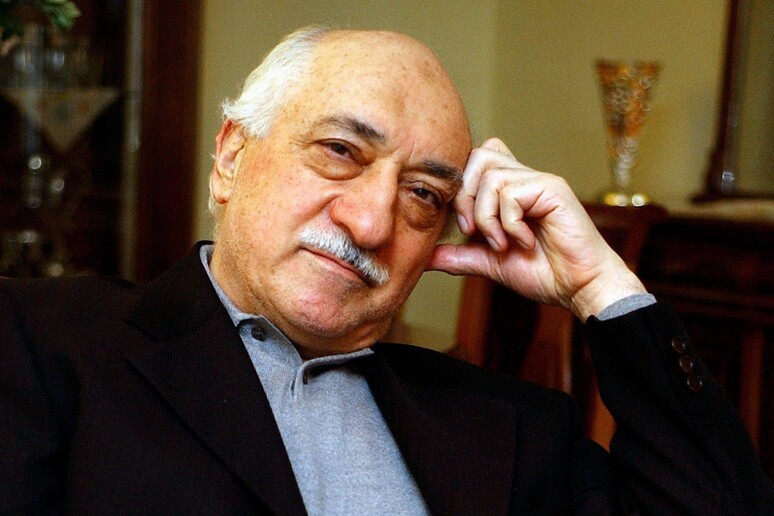

Fethullah Gülen, a controversial Turkish Muslim cleric and leader of the Hizmet (“Service”) movement, passed away Sunday evening in a U.S. hospital at the age of 83. The news was confirmed Sunday by his associates, who did not specify the cause of death.

Born in 1941 in Pasinler, a rural district in eastern Anatolia, Gülen had lived in self-imposed exile in Saylorsburg, Pennsylvania, since 1999, from where he coordinated a global network of schools and social organizations linked to Sunni Islam.

The leader’s demise marks a watershed date for Hizmet, already weakened by years of draconian repression by authorities in Ankara, who accuse the Gülenists of orchestrating the failed 2016 coup. Since then, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has labeled the movement a terrorist group, officially rebranding it as the “Fethullahist Terrorist Organization” (FETÖ), while unsuccessfully pushing for the extradition of its founder from the U.S.

Yet Gülen and the “sultan” were once more than just good friends. Both shared a common conservative Islamic heritage typical of deep Anatolia, where Istanbul-born Erdoğan spent his childhood. Notably, both aimed to restore Islam to the center of the republican institutions that Mustafa Kemal Atatürk had founded on a strict principle of secularism.

Since its establishment in İzmir in the late 1960s as a Quranic school, Hizmet has financed schools and cultural centers worldwide, from Central Asia to Africa, Europe, and the United States. However, Gülen chose to focus his proselytizing activities primarily in his native country.

Elected prime minister in 2003, Erdoğan recognized that the movement could be a valuable ally due to its extensive network of schools, cultural institutions, and media outlets across the country, along with an electoral base of nearly two million affiliates. This served the dual purpose of increasing his popularity and undermining the old secular establishment, particularly within the military loyal to Atatürk.

After about a decade of camaraderie, the peak of their alliance came in 2008. In that year, Ankara’s Constitutional Court, by the slimmest of margins (6-5), chose not to dissolve Erdoğan’s AKP party despite its apparent violation of secularism—a charge that had previously led to the banning of the Virtue Party, where Erdoğan had started his post-prison political career.

With political Islam having gained legitimacy, the increasingly pervasive presence of Hizmet members within state institutions began to be viewed as a threat by Erdoğan and his AKP, prompting them to distance themselves from an ally that had become more of a liability than an asset.

The definitive break came with the failed coup attempt in July 2016, which resulted in the deaths of over 250 people before Erdoğan’s loyal forces managed to repel the coup plotters. Almost immediately, Erdoğan explicitly accused Gülen of orchestrating the uprising and initiated a sweeping purge that ultimately affected even leftist opponents of his government: 100,000 people were arrested, and another 150,000, including teachers, judges, and military personnel, were dismissed or suspended. Thousands of schools, newspapers, and other institutions deemed linked to Gülen’s network were violently suppressed.

According to nearly unanimous expert opinion, this marked the genesis of the Islamist regime’s autocratic turn, which the following year would rewrite the “coup constitution” (referring to the military coup of 1980) and establish an hyper-presidential regime, enabled by a narrow victory for the “Yes” votes in the referendum.

Once again, the religious breakthrough was made possible by Anatolia, whose massive Islamist consitutencies voted en masse in favor of the proposal, successfully counterbalancing the opposition from the metropolitan areas.

For many of Gülen’s followers, he was more than just a spiritual leader or educator. Some revered him as a nearly messianic figure, seeing in him the “Mehdi,” the savior of Islam who, according to Muslim tradition, will emerge at the end of times to guide the faithful toward the global dominance of the Ummah. This vision fostered a cult of personality around Gülen, sometimes strengthening his followers’ devotion even after his self-imposed exile.

With the death of its leader, however, the Hizmet movement now faces a jolt that could amplify internal divisions and accelerate a seemingly inexorable decline. What was once a thriving global network has now become an empire downsized by Ankara’s diplomatic pressure on the various countries in which Hizmet is struggling to operate. This includes the United States, whose long-standing refusal to extradite Gülen has been a persistent thorn in relations with Turkish authorities, further fueling a conspiracy theory—never denied by Erdoğan—that the preacher was merely a “puppet” of the CIA.

Yet troubles also brew from within. Well-informed sources indicate that a feud has been ongoing for years between the movement’s leadership in the U.S. and its European followers. Central to this conflict is Cevdet Türkyolu, one of Gülen’s chief collaborators and potential successors, accused by some dissenters of arbitrarily seizing control of the movement’s financial resources.

Finally, there remains the practical question of how to bury Gülen. The location of his grave will most likely be kept secret to prevent it from becoming a symbol for his followers—or a target for his numerous and powerful detractors.