Joy Hirsch, a neuroscientist from Yale, utilized sophisticated imaging techniques to observe the brain activity of two people conversing live; she detected complex patterns of neural engagement in the regions responsible for social interactions. Yet, when she employed the same methods while using the widely-used video conferencing platform Zoom, she noted a distinctly different neural response.

Neural signaling was significantly suppressed compared to the behavior observed in individuals engaging in face-to-face conversations.

“In this study, we find that the social systems of the human brain are more active during real live in-person encounters than on Zoom,” said Hirsch, the Elizabeth Mears and House Jameson Professor of Psychiatry, professor of comparative medicine and neuroscience, and senior author of the study. “Zoom appears to be an impoverished social communication system relative to in-person conditions.”

Her team points out the importance of social behavior in our collective evolution as a species and a society; processing dynamic facial cues is a primary source of social information and is an activity that we are genetically optimized to perform subconsciously.

Hirsch’s study stands out because, for the first time, they were able to develop neuroimaging technologies that allowed them to monitor interactions between two individuals interacting at once. Previous studies almost always focused on single-subject imaging at a time.

Hirsch and her team analyzed interactions between two individuals, differentiating between two pools of live, in-person interactions and then conversations conducted through Zoom. The increased neural activity of those engaged in in-person interactions was notable and was associated with increased gaze time and pupil size, this is suggestive of increased “arousal” in the two brains.

Neural imagining also showed elements of coordinated activity between two brains engaged in live interaction, suggesting increased reciprocal exchanges of social cues between the two individuals.

“Overall, the dynamic and natural social interactions that occur spontaneously during in-person interactions appear to be less apparent or absent during Zoom encounters,” Hirsch said. “This is a really robust effect. Online representations of faces, at least with current technology, do not have the same ‘privileged access’ to social neural circuitry in the brain that is typical of the real thing,”

The notion that the digital medium is an “impoverished” replacement for real in-person interaction may not be a groundbreaking revelation, but its quantification is what’s important. If Hirsch could have gone further, it would have been interesting to see how neural activity changed by elongating the spectrum past simple video-conference technology that has existed for over a decade.

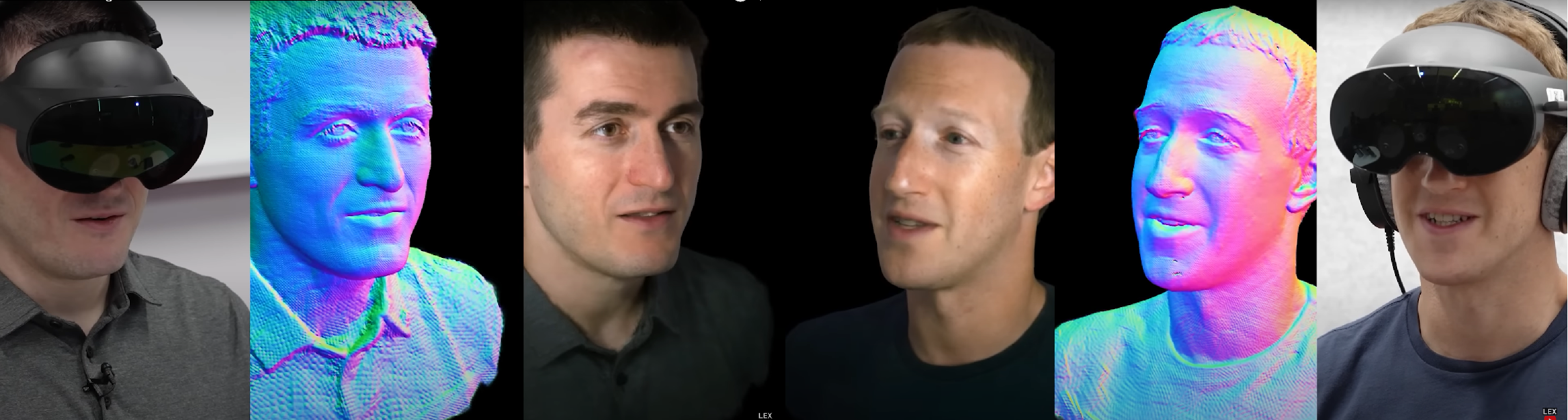

Just a month ago, popular podcaster Lex Fridman hosted Mark Zuckerberg for an interview that was conducted completely through VR technology; the unique format resulted in clips being widely shared online. It would be extremely valuable to know how such technology impacts neural activity when compared to Zoom conferences. Could it be markedly improved with our tech or would results indicate that no matter the medium there is no substitute for the crucial social interactions that dictate our day-to-day lives?