In academia, there is no quicker or surer career killer than being accused of plagiarism or of faking data—both are considered fraud. Not only will this generally get one fired, but it may also create a stigma that will prevent any further employment in the ivy halls.

This is the kind of scandal that Italian American scholar Francesca Gino, professor of business administration at Harvard Business School and a renowned researcher on topics such as decision making, ethics, and creativity, is embroiled in.

Gino grew up in a tiny Italian mountain town of 3,000 called Tione di Trento. She attended college at the nearby University of Trento before earning her master’s and Ph.D. at the Sant’anna School of Advanced Studies in Pisa. While completing her Ph.D. in 2002, Gino went to Harvard as a visiting fellow. She was supposed to stay for six to nine months, but instead, as she wrote earlier this year on LinkedIn, “I never left.”

Gino conducted her postdoctoral research at Harvard and then went on to teaching gigs at Carnegie Mellon University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Soon, she was receiving job offers from top universities across the US, including Harvard Business School. By the time she was 32, she was back at HBS as an associate professor and “already this superstar,” said a former collaborator.

Gino has parlayed her research into what is being called an “empire”, though how an empire fits into academia is a mystery to those of us who are in it. Suffice to say that in Gino’s case, there were indeed a lot of money and reputation involved. She has published more than 100 articles in prestigious journals and authored several books, including “Rebel Talent” and “Sidetracked”, titles that ironically proved to be prophetic as to her professional trajectory. She has also received numerous awards and honors for her academic contributions and teaching excellence.

From 2019 to 2020, Gino raked in more than $1 million as a professor at Harvard Business School, studying trendy topics such as political correctness and why people lie.

However, while riding high, Gino’s reputation was suddenly tarnished by a serious allegation of academic fraud.

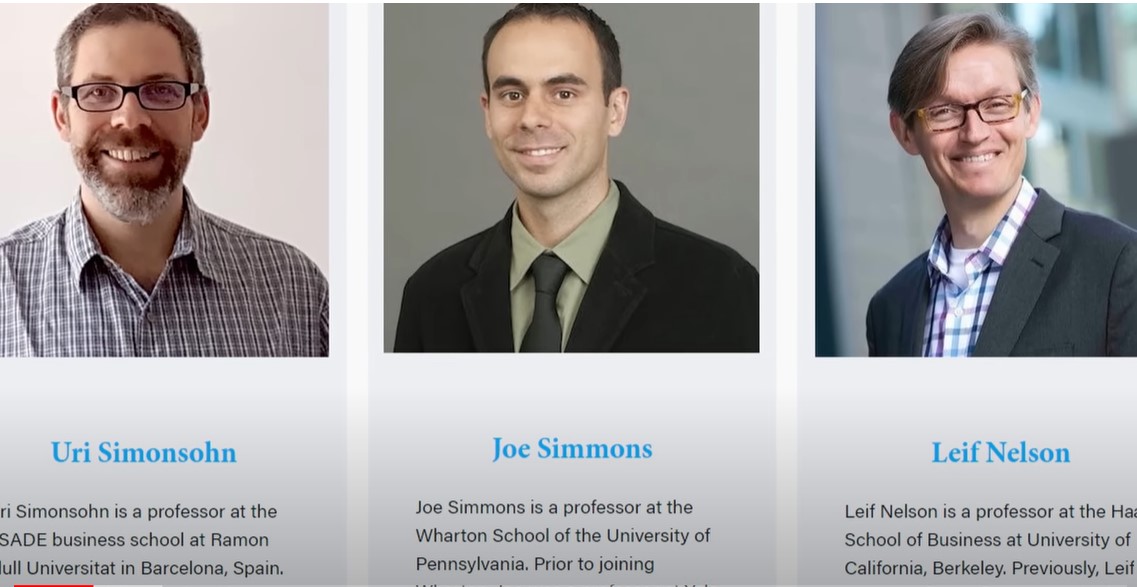

In mid-June, news broke that Harvard had placed Gino on administrative leave after an internal investigation into allegations that she falsified research data. The next day, Data Colada — a blog run by three professors and known for exposing shoddy research — published its first of four posts saying it had found evidence of fraud in Gino’s work. Data Colada reported that Harvard’s still unreleased internal report on Gino was roughly 1,200 pages.

“We believe that many more Gino-authored papers contain fake data,” the Data Colada professors wrote. “Perhaps dozens.”

A team of independent researchers claimed that they had found evidence of data fabrication in several of Gino’s studies, including one on dishonesty that she co-authored with Dan Ariely, another prominent behavioral scientist who was also accused of data manipulation. The researchers said that they had detected statistical anomalies, inconsistencies, and implausible patterns in the data reported by Gino and her collaborators. They also said that they had contacted Gino and asked her to share the original data files, but she had refused or failed to do so. Whether this was so that her duplicity and manipulation of data would not be discovered we cannot say.

A behavioral scientist who took a deep dive into her research concluded that “the results are shocking.” Another branded her work as “quite cute.” In academia that is not a compliment. “They’re sort of designed to be turned into pop books or TED Talks,” he added, underlining that pecuniary gain and popular glory is antithetical to the very spirit of scholarly research.

The allegation sparked a major controversy in the academic community and the media. Many of Gino’s colleagues and former students expressed shock and disbelief at the possibility that she had engaged in scientific misconduct.

It is well-known that academia is a cutthroat business and that there is a mad race to be first to publish groundbreaking ideas and theories—and that they must also be presented in a manner that attracts wide notice. Gino’s ideas rode the crest between original and bizarre: shaking hands makes people more likely to agree on deals, or that networking makes people feel so dirty that they develop a sudden interest in cleaning products.

It was not only Gino’s reputation at stake, but that of as many as 150 other scholars who had collaborated on the research, the papers and the books.

Some colleagues defended her integrity and questioned the validity of the accusation. Others called for a thorough investigation and urged Gino to cooperate and provide transparency. Gino herself issued a statement denying any wrongdoing and saying that she was working with Harvard to address the issue. She also said that she was taking a leave of absence from her teaching and research activities.

The Harvard fake data scandal, as it came to be known, is not only about Gino, but about Harvard and academia in general. It raised serious questions about the credibility of behavioral science and the ethics of research.

After her initial silence, on August 2 she filed a 100-page, $25 million defamation lawsuit against the Data Colada researchers and Harvard.

“I want to be very clear: I have never, ever falsified data or engaged in research misconduct of any kind,” Gino wrote on her LinkedIn page. “Today I had no choice but to file a lawsuit against Harvard University and members of the Data Colada group, who worked together to destroy my career and reputation despite admitting they have no evidence proving their allegations.”

The outcome of this lawsuit is a long way off, but some of her colleagues already have a verdict of sorts: Gino prioritized speed over substance. “I didn’t think it was fraud, but I thought it was bullshit,” said Simine Vazire, a professor of psychology, ethics, and well-being at the University of Melbourne.