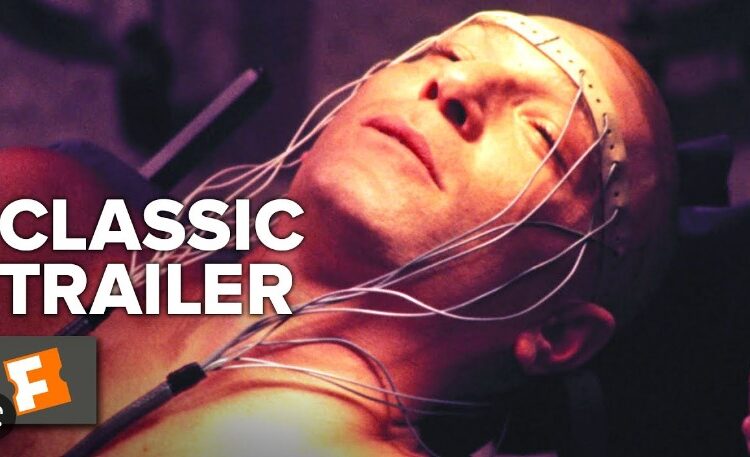

Elon Musk never stops thinking about tech innovations. Whether these are good or not for human beings is secondary to the main point: innovation. Now, taking inspiration from sci-fi movies such as Upgrade, Terminal Man, AI and Total Recall, he wants to put a computer chip in your brain.

Musk’s neurotech startup, Neuralink, has been working toward implanting its skull-embedded brain chip in a human since it was founded in 2016. After years of testing on animal subjects, Musk announced in December that the company planned to initiate human trials within six months (though this wasn’t the first time he’d said these trials were on the horizon).

Neuralink has spent over half a decade figuring out how to translate brain signals into digital outputs — imagine being able to move a cursor, send a text message, or type in a word processor with just a thought. While the initial focus is on medical use cases, such as helping paralyzed people communicate, Musk has aspired to take Neuralink’s chips mainstream — to, as he’s said, put a “Fitbit in your skull.”

Musk’s company is far from the only group working on brain-computer interfaces, or systems to facilitate direct communication between human brains and external computers. Other researchers have been looking into using BCIs to restore lost senses and control prosthetic limbs, among other applications. While these technologies are still in their infancy, they’ve been around long enough for researchers to increasingly get a sense of how neural implants interact with our minds. As Anna Wexler, an assistant professor of philosophy in the Department of Medical Ethics and Health Policy at the University of Pennsylvania, put it: “Of course it causes changes. The question is what kinds of changes does it cause, and how much do those changes matter?”

In the 1974 film “The Terminal Man,” a man gets an invasive brain implant to help with his seizures. While the operation initially seems to be a success, things go badly when sustained exposure to the chip sends him on a psychotic rampage. As is typically the case in sci-fi movies, a scientist warns of the disaster early in the story by comparing the implants to the lobotomies of the 1940s and 1950s. “They created an unknown number of human vegetables,” he says. “Those operations were carried out by physicians who were too eager to act.” This should be a warning in real life as well as n the movies.

Recent improvements in artificial intelligence and neural-probing materials have made the devices less invasive and more scalable, which has naturally attracted a wave of private and military funding. Paradromics, Blackrock Neurotech, and Synchron are just a few venture-backed competitors working on devices for paralyzed people. Last November, a startup called Science unveiled a concept for a bioelectric interface to help treat blindness. And last September, Magnus Medical got approval from the Food and Drug Administration for a targeted brain-stimulation therapy for major depressive disorder. These, of course, are wonderful examples of the miracles that innovation can create.

However, while there have been no confirmed cases of “Terminal Man”-style violent rampages caused by BCIs, compelling evidence suggests the devices can cause cognitive changes beyond the scope of their intended applications.

As the technology improves, we get closer to Musk’s “Fitbit in your skull” vision. But there’s reason to be cautious. After all, if it’s easy to get addicted to your phone, just think how much more addicting it could be if it were wired directly into your brain.

Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, who should know a bit about tech addictions, has said, “One day, I believe we’ll be able to send full rich thoughts to each other directly using technology. You’ll just be able to think of something and your friends will immediately be able to experience it too if you’d like. This would be the ultimate communication technology.”