The direct origin or “source” of geopolitical threats is an open question. There is no systematized view of the nature of the phenomenon, and there is no model that describes it. Every inhabitant on the Earth, in one way or another, directly or indirectly, is exposed to geopolitical threats; for instance, one of the simplest manifestations in our daily lives is when a person feels a change in his quality of life.

The significance and urgency of the study of global threats are unquestionable. More and more often, contemporary security experts and business consultants, theorists and practitioners, scientists and minds seekers are discussing practical categories related to: how to be and what to do when a person finds himself at the epicenter of a “geopolitical centrifuge,” whether it is a pandemic, hybrid war, information scenario battle or technological confrontation affecting economic and social indicators. Each of us is, in one way or another, neither free nor immune to changing environmental conditions. The helplessness and potential danger of an unmanageable future due to a lack of understanding the nature of global threats is a powerful lever and reason to scientifically explore the phenomenon.

At the heart of this research approach lies a dilemma of methodological choice: which scientific discipline has the apparatus that allows the comprehending of this category? To which “scientific section” does the topic belong?

The key “contenders” are political science, history and psychology. Thus, modern political science increasingly shifts its research focus to the “matters of the present,” neglecting the lessons of the past; therefore, in my view, this discipline has the weakest methodological standing. Certainly, the interdisciplinary approach has the most remarkable advantages; but it is worth noting that history as a discipline is paramount for understanding the topic. Provided there is reliable historical data, it is possible to comprehend the trends in the deployment of geopolitical threats and their frequency. Trends, in particular, will allow us to trace the systematic development of the phenomenon and the frequency of significant events generated by threats of this order. Studying trends also enables researchers to note the frequency of the emergence of geopolitical threats. A separate scientific task of exploring the scaling of threats, why and how it is possible is also as relevant as ever.

The research subject here is the nature of geopolitical threats—the immediate root that scales globally. The subject of the study is a dynamic scheme that reflects the nature of the geopolitical threat. Based on the prototypological approach, it is suggested to critically analyze: 1) global trends as a reflection of the systemic development of “global threat” as a phenomenon; 2) the frequency of events; 3) the scaling of threats.

From which historical point of our civilization should geopolitical threats be studied? From the view of a chronological timeline, considering the concept of the unity of the “past-present-future,” it is suggested to consider the 15th century as an appropriate starting point in the study of geopolitical threats. “Reasonable” history—the events of which are subject to assessment and critical reasoning, perhaps, starts from the 15th century because there are significant amounts of documents and artifacts on the subject that have survived since then, consequently permitting a comprehensive study of the nature of global threats. In theory, we can converse about earlier historical events, but objectively we have almost no verifying documents. To some extent, we would like to discuss the events of the era of Genghis Khan and Batu Khan. Unfortunately, most of the documentary evidence earlier than the 15th century are questionable in its completeness and reliability. Although, for example, the concept of “a rich country on a scale from ocean to ocean, where any woman could stroll with a golden tray and feel safe” is quite inquisitive, and from the perspective of modernity, it is utopian.

Geopolitical threats presuppose the presence of such an institution as the state. Accordingly, if the 15th century is chosen as the starting point, the primary source of geopolitical threats has been empires. The desire and power to conquer new territories to enlarge empires, and the politics and the science of governance brought some order to their changing boundaries. Certainly, it was not the conquerors who regarded “empire” as a source of threats, but the inhabitants of conquered territories, who often did not accept the “new imperial order.” History is replete with cases of “rejections of the order,” from isolated local strikes to widespread unrest. Probably the only historical example of a wise ruler who was not perceived by his subordinates as a threat to their existence or encroachment on their way of life is Charles V. A rare, even unique example of a ruler who managed to maintain an equilibrium of “new and old” as the Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain. However, this example of a wise politician who skillfully combined the approaches of justice and efficiency, prototypically comparable to those of King David and King Solomon, is an exception to the rule rather than a common historical norm.

It is reasonable to think of the desire to build an empire as a psychologeme. Why would anyone want to build an empire at all? Particularly if one already has power, wealth, natural and human resources at their disposal. From a psychological viewpoint, I suppose that the purpose of building an empire is to scale the personality. Having studied the legacy of the Spanish Empire and the phenomenon of Charles V for more than a decade, it should be emphasized that this particular case is not so simple and straightforward. In particular, the narrative of Charles V’s ascent to the throne, given the vast number of “more eminent pretenders,” is a true mystery.

Nevertheless, the development of any empire involves such processes as the seizure of territory and the establishing an imperial order on it. The main motive (using the Spanish Empire as an example) is religious, i.e. the spread of Christianity. History indicates that the era of the Christianization of Europe was replaced by a more consequential event—spreading Christianity throughout the world. How this became feasible is another question. This kind of reasoning makes it possible to reach an important conclusion: thus, any threatening factor is preceded by a philosophical idea. Try to think of war, battle, invasion, or conquest, the actualization of which would not be preceded by a philosophical argument. In some cases, it is a religious-philosophical idea, but by no means always. However, every threat on a global scale is preceded by a philosophical idea.

Philosophical ideas can be grounded on absolutely different preconditions: from the seizure of territory to the enrichment and strengthening of the scale of power; actualization of private economic interests—for example, the redistribution of the market; religious motives—the dissemination of religion, etc. For instance, the Christianization of Europe is a flamboyant episode and an explicit example that contributes to understanding the nature of geopolitical threats and the tactics of their imputation. Introducing changes to the way of life is a task on the verge of “impossible” without a specific lever of force. And the spread of a new religion falls right into such a category of missions. Thus, the Christianization of Europe was preceded by the creation of particular prerequisites: 1) a widespread threat on the European continent, namely the plague; 2) a terrible disease that took millions of lives became “fertile ground” for fostering and spreading the idea of “salvation” (the death toll was extreme). It seems that it wouldn’t have been possible to Christianize Europe without the idea of “salvation.” The fact remains that disease (the plague) preceded the Christianization of Europe. The Spanish conquest (colonization of the Americas) is oftentimes associated with enrichment and the quest for “a hidden city, built entirely of gold.” However, the fact that the conquistadors themselves carried the idea of “salvation” (the driving motive), followed by the establishment of a new imperial order in the conquered territories, is not insignificant.

No less important is that often those who were “saved” did not want “to be saved” at all (this tendency is characteristic not only of the Middle Ages, but as the saying goes, nothing has changed, and this tendency is prevalent in our days too). The objective of the geopolitical threat is to control and govern, that is, to establish control and exercise control over a certain territory, not just a city or a region, but a continent, a part of the world.

World War I is the fundamental historical range to be studied to puncture the mystery of the nature of geopolitical threats. In the course of the related discourse, let us note that the philosophical idea determines the state’s policy, and the policy dictates the causes of the genesis of the geopolitical threat.

Figure 1

Figure 1

WWI plainly revealed what the “difference of political opinion is” and how the conflict of “different views on how the world and life are supposed to look” can end. Contingently, not everybody is capable of initiating these kinds of large-scale confrontations. It would be reasonable to say that only those who have the actual power to change something (the rulers, important politicians, representatives of the upper echelons of power, and so on) can do this. Simply put, those with an army at their disposal can seize some territory and establish the “necessary order” there.

Thus, the difference in philosophical ideas played a key role in causing the preconditions for the deployment and scaling of the military conflict that eventually reached the dimensions of WWI. However, differences in worldviews are not the only factors that lead to such global conflicts in history. In the previous case, the “owners” of philosophical ideas had a combat-ready army apparatus at their disposal. Military formations acted in the interests of ruling circles, giving orders for military operations; however, outside, within the political arena, declared different goals. For example, “to ensure the protection and security of innocent civilians,” the “establishment of a new order” was not, of course, announced aloud. By analogy, one involuntarily recalls the science fiction work “The Genetic General” by Gordon R. Dickson. There is a scene when the main character reports at the Palace of the Justice League, that depicts the public statements of the ruling elite as far from being consistent with their original intent. And that “it is not enough to win the war, it is important to do the will of those who sent you.” And the “will of those who sent you” is, more often than not, unknown to the doers, let alone the civilian population. I present examples of this kind (including examples from literature) to illustrate that the geopolitical threat is a concealed threat. We do not always understand its ultimate goals.

On the one hand, WWI was the war of philosophies. On the other hand, by looking into the prerequisites for the geopolitical threats of WWII, it is possible to conclude that the key factors were economic reasons, not ideological. Although the USSR, France, Great Britain and other countries won, at the end of WWII a different country economically prevailed and enriched itself in the field of global conflict. It was the U.S. that became a “superpower” at the expense of WWII. The enrichment of the United States (including military supplies of weapons, equipment, “saving” the gold reserve of some European countries, etc.) on a global scale would not have taken place without the exploitation of the “world war” factor as a total threat.

To compare: the USSR, having won the war, lost a massive number of lives and had to rebuild their ruins and often their entire infrastructure among other things, while no military action on a scale comparable to that of Europe took place on U.S. territory. The episode with the disappearance of the German gold reserve (and not only) is a separate “gray area” in the economic history of the U.S. No other “event,” “action,” or “international undertaking” has given the U.S. such a bounty as WWII. A similar comparison of the preconditions for the unfolding of the world wars allows us to conclude that the nature of geopolitical threats goes back not only to philosophical categories and grounds, but also to the causes of the economic order.

Philosophical War → Economic War

Thus the philosophical war was transformed into an economic war. While the example of the Conquista does not allow us to draw indisputable conclusions (not everything is known about the colonization of America and it is challenging to verify the events of those centuries today), recent history provides concrete data for critical analysis.

The following results from a praxeological reflection on the nature of the geopolitical threat.

The scheme of geopolitical threats’ realization:

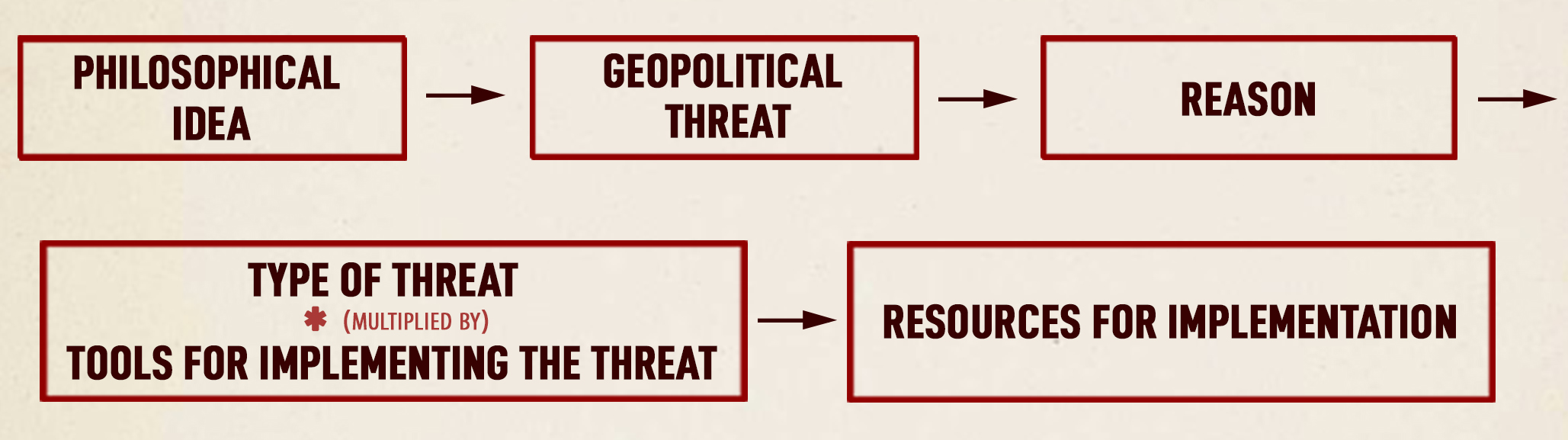

Figure 2

Philosophical idea → Geopolitical threat → Reason (philosophical, religious, economic, etc.) → Type of threat (multiplied by) Tools for implementing the threat (war, epidemic, hybrid war, etc.) → Resources for implementation, in particular, the selection of the institution that will “implement” the project.

As an explanation of the scheme: a philosophical idea precedes any geopolitical threat; it generates a cause for future “world re-transformation,” be it economic or religious-philosophical interests, etc.; the motive generates the type of threat and the instrument of its implementation (what exactly will be introduced: war, epidemic, impending ecological catastrophe or something else); which obviously requires resources for threat realization, i.e. what “body” or formation will implement the threat project (army, monastic corps, order or others).

The scheme of implementing the geopolitical threat leads to the following deduction: at the heart of any geopolitical threat lies a difference in the mentality component.

As an example, consider the conquest of the “Wild West” and the extermination of the indigenous North American peoples, the remnants of whom the conquerors “placed” in reservations. The concept that “those in power are right” (biological rather than cultural and social) only served as a catalyst for economic causes and motives. The war for the Holy Sepulchre was also not limited to religious dogma. Yes, the waves of the Crusades were preceded by the idea of a “war for the stolen Holy Sepulchre,” were “justified” by the religious tenets of Christianity; but one of the true causes of European expansion is an economic one, with the ultimate goal being to plunder the East and create private enrichment.

Thus, the true causes of geopolitical threats are hidden with a “reasonable wrapping.” Comprehension of the way global threats are implemented is usually subjective. The participants of events, perforce subjected to pressure or directly impacted by the instrument of geopolitical threat, are typically unable to adequately assess the related cause-effect relations. The idea of “salvation” is not new at all. What one side claims, for example, to be a “rescue operation to restore order and prevent the outbreak of a global military conflict” is, for the other side, a real invasion by “liberators who are not welcome” because there is no need for a “rescue” as such. This example is given to demonstrate the consequences of a clash of different mentalities.

We conclude with another retrospective look at the personality of Charles V—the ruler of the empire on which the sun never sets, somehow managed to maintain a balance, taking into account the peculiarities of the mentalities of different peoples (including the conquered). How did Charles V act tactically, ideologically or socially, and why did his figure inspire confidence and respect among his subjects even in the occupied territories? Without excessive idealization, similar questions outline a new quest to explore the mentality and management of the nature of geopolitical threats, as well as subsequent practical investigations into the instrumentalization and systematic development of life tactics under the impact of global threats.