Thirty years ago this month, “police burst into an office in Milan where the chairman of Pio Albergo Trivulzio, a leading charitable institution, was in the process of pocketing a bribe. He was charged with taking a kick-back for the delivery of every cadaver that went from the charity’s old people’s home to the “correct” funeral parlor. The raid had been ordered by a dynamic, unpredictable, workaholic Milan magistrate, Antonio Di Pietro, an ex-cop whose open collar and five-o’clock shadow would soon be featured in hot-selling T-shirts throughout Italy. A few months later, polls showed that he was the most popular man in Italy.”

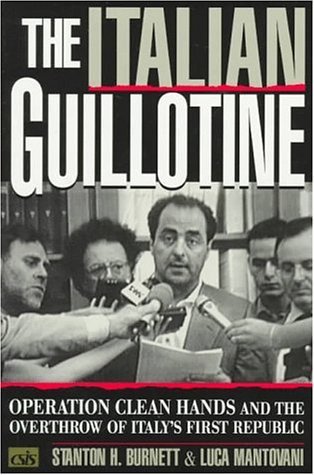

That’s from the opening paragraph of The Italian Guillotine, a book published in America in 1998. I had, along with many Italians and most outsiders, been swept along by the news reports of a brave band of Milanese magistrates making a frontal assault on a major arena of political corruption in Italy: the secret funding of the country’s major political parties. There was no demand for a different, less noble version of this assault, but…something didn’t smell right.

That’s from the opening paragraph of The Italian Guillotine, a book published in America in 1998. I had, along with many Italians and most outsiders, been swept along by the news reports of a brave band of Milanese magistrates making a frontal assault on a major arena of political corruption in Italy: the secret funding of the country’s major political parties. There was no demand for a different, less noble version of this assault, but…something didn’t smell right.

When I expressed my doubts to a good friend, Massimo Pini, a close colleague of Bettino Craxi, he voiced no opinion on the phone. But a few days later, Pini’s Mercedes wheeled into the yard of the farmhouse in Burgundy where my wife and I were spending a bucolic year. Two nuits blanches followed as, along with a brilliant young journalist and skilled researcher, Luca Mantovani, I read through stacks of documents, and felt the furniture of my mind being rearranged.

There was no doubt that the magistrates had collared some guilty parties. But why? Why these magistrates? The sleazy golden relations between parties, big business and other sinister forces with deep pockets had been going on for years. The Right had long accused Moscow of funding the PCI and the Left countered with the claim that Washington kept the Christian Democrats and Social Democrats afloat. But Mani pulite was not about foreign influence. It was about the poisoning of the Italian political stew with toxins that were home-grown.

The resulting book was researched, written and published for one reason: the naïve hope to spark reform. As such, this perfect storm was a perfect failure.

It did play a role in changing some perceptions. The belief in, and popularity of, the Milan magistrates plummeted in polls and became a controversial issue, not a given. To my bitter dismay, it helped Silvio Berlusconi wiggle through the smoke screen of charges and counter-charges successfully enough for two long terms as prime minister. It led to some small strategic changes in magistrates’ public spectacles. None of these would have been worthy goals even if they had been intended.

Now, thirty years later, the independence of the judiciary from any institutional controls remains intact. Double jeopardy is a method, not a crime. Habeas corpus lies dead under a stack of suicides and broken men, all victims before trial. Magistrates jump easily between the roles of prosecutor and judge, with only the inconvenience of moving a couple of doors down the hall; they all belong to the same collegial squadron.

The result is that Italian magistrates wield a power in Italian political life that is uncontrolled by the other branches of government, unmoderated by any tradition of judicial reserve, and unmatched for its stark independence by that of any other major Western country.

The book, whose Italian translation was blocked because it was a cruel distortion of the book’s meaning, (a failure to appear in Italian that was predicted by the dean of American political scientists working on Italy, Joseph LaPalombara, in his initial review of the book), has, year after year, seen its assertions verified by the years-too-late testimony of some of the participants and close observers. But, in the end, it appears to me to have had no serious impact on the system it impeached.