Last week, while I was watching a nationally televised panel discussion on Covid-19, a viewer with a background in medical research asked a simple question: What if we cannot develop a viable vaccine against Covid-19 within the next 18 months? Every member of the panel was dumbfounded and fumbled their responses.

None of them, not the union leader, not the politicians on both sides of the divide, nor any of the medical experts had given thought to what would happen if an effective vaccine could not be developed within a year or so.

Covid-19 first came to Australia’s shores via Chinese tourists on January 25. The five state and two territory governments of the Australian federation immediately put into action their plans for pandemic containment. This consisted in border closures, extensive testing and quarantine. Despite some initial failures, particularly in regard to infected passengers disembarking from cruise ships, these efforts were ultimately successful in suppressing if not eliminating Covid-19.

Australia’s health care is delivered by a mixed public and private system. The public system provides all levels of health care free of charge to the whole population. The private system, funded by non-compulsory private health insurance, caters for those who wish to avoid waiting lists for elective surgery, prefer private hospitals and choice of medical personnel.

It was the public system that responded to the pandemic by delivering free testing and medical care to everyone. The government also secured the agreement of private hospitals to make their beds available to Covid-19 patients in case of bed shortages in the public hospitals.

For their part, the state governments enforced stringent lock-downs. At the same time the Federal government increased social security payments and extended their eligibility for those who lost their jobs because of closures or restrictions placed on the tourism, hospitality, retail and higher education industries, which employ the majority of the population.

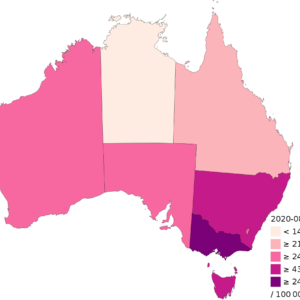

Together, these coordinated measures were largely successful despite occasional hot-spots, particularly in private aged care facilities. Between the end of January and the end of July the death toll never went beyond seven people per day out of a total population of over 25 million people.

It seemed to many that we had dodged the full force of the Covid-19 onslaught. Restrictions were relaxed throughout Australia, except on international arrivals and departures. Unfortunately, at the end of July, in the state of Victoria, whose capital city is Melbourne with over 5 million inhabitants, the scenario changed for the worse.

The virus escaped from two Melbourne hotels where Australian tourists returning from abroad had been quarantined. A hotel staff member caught the disease, then infected security guards, who in turn spread the disease to their families. Contact tracing units tasked with determining the origins of the infections were soon overwhelmed. Contagion spread rapidly to public housing estates, abattoirs and then to the private aged care sector, which to date has suffered two thirds of total deaths. The daily death toll now ranges between the teens and the low twenties. Overall deaths number 334 in Victoria alone and 421 nationwide.

The Victorian government, which is governed by the Labour Party, became the target of political attacks from the right leaning Murdoch owned media and the Liberal-National Party Coalition. The national Liberal-National Party Coalition is currently governing the Federation.

Initially, the security guards, who are often immigrants or Australian citizens from non-English speaking backgrounds were accused by right-leaning media of being sloppy, ignorant or non-compliant. One guard was even accused of having had a sexual liaison with a quarantined person. Their local communities and families, some of whom hold the Islamic faith, were blamed for not respecting the lock-down provisions because of their Ramadan and Eid al-Adha festival celebrations. The Victorian government was also lambasted for not providing adequate translations in community languages to explain lock-down measures, for seeking to save money on security and for not asking the Federal government to send in extra help. The same state government was accused of imposing too harsh a lock-down on public housing estate residents from the left.

Then the state government and the federal government began to wrangle over the excessively high death rates in the private aged care sector, which is a federal responsibility. Victoria was placed under a state of emergency and a curfew enforced between the hours of 8 pm and 6 am. The lock-down regime was rapidly increased from stage 2 to stage 4, which means that everyone must remain at home. One hour of exercise per day and shopping for essentials is allowed only within a five kilometre radius from one’s place of residence. Visiting friends or relatives is prohibited except to provide them with care. Work is restricted to essential professions under a permit system and masks are compulsory whenever outside.

Despite these draconian measures, there are currently still over 200 new infections per day. Many of these are among people either living or working in aged care facilities and medical personnel for whom the state is still struggling to provide protective equipment. Discussions are afoot with the federal government to bring in the army to assist with quarantine security and the medical emergency. The other states, which have had much lower to nil cases of Covid-19, have sealed their borders to Victorians.

Although Victoria is still in the throes of the pandemic a consistent pattern has emerged: in nearly every instance those most exposed to the disease have been the lowly paid and low status workers in essential service industries. Often, they are recent immigrants from non-English speaking backgrounds who have been charged with the care of others under impossible and dangerous conditions. Sometimes these workers, frequently in casual positions, are forced to work even when unwell and to work in multiple places to be able to survive given their low wages. Many are falling ill and sometimes dying along with the frail elderly or disabled people whom they are assisting.

At the same time, the highest paid workers, generally in non-essential occupations, are comfortably working from home. And the politicians on the right are continuing to snipe against the beleaguered government of Victoria and its political leader, Premier Daniel Andrews, to whom they have attached the derogatory epithet of ‘Chairman Dan’ for his anti-pandemic measures.

If the Covid-19 pandemic has taught us anything it is that the value systems of our societies are totally distorted. Workers in the vital professions that provide care for others are precisely those with the lowest status, pay and conditions. This is a reality that immigrants, and women in particular, have been familiar with for a long time. But it has taken a deadly epidemic to bring these injustices to the public’s attention.

As many have pointed out, this pandemic has not so much changed things as revealed the underlying dynamics of our society and economy. To return to the question posed to the panel of experts and politicians: what if an effective vaccine is not forthcoming in the near future?

Much as we have done with climate change, we have invested our faith, if not our critical faculties, in science with the unrealistic expectation that somehow it will find a silver bullet solution to our self-generated crises. But as Einstein once said: “We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.”

We need to ask ourselves whether our current economic and by extension social paradigm, premised as it is on infinite growth at the expense of nature, is ultimately sustainable. And by nature, I am also referring to the nature that abides in ourselves.