A marathon summit, second only to the one held in Nice in 2000; over 90 hours of talks, four nights and almost five days marked by variable geography meetings to approve the European Recovery Plan, Next Generation EU (NGEU), and the Multi-annual Financial Framework (MFF), the EU long-term budget, which represents the pivot of NGEU.

Three highly sensitive issues for EU Heads of State and Government during the negotiation:

- total amount for the Recovery package: the so-called “Frugal4 Countries” (the Netherlands, Austria, Denmark, Swedish) and Finland asked for a consistent reduction, especially for grants;

- governance of the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF), through which a substantial portion of the grants will be paid;

- conditionalities on rule of law and the EU climate neutrality objectives.

- Regarding the total amount: on May 27, the European Commission had submitted a € 750 billion proposal for NGEU, with a 30-70% proportion between loans and grants: 250 billion in loans and 500 billion in grants.

The agreed-upon compromise confirms the endowment of Next Generation EU at 750 billion but changes its proportions, substantially leveling the amount of grants and loans, bringing them to 390 billion and 360 billion respectively at 2018 prices.

Compared to the Commission proposal, Next Generation EU earns 110 billion in loans, but it cuts its non-repayable grants for some strategic programs: React EU (Structural Fund), “Horizon Europe” (R&I); Invest EU (Firms), Solvency Support Instrument (recapitalization and solvency of companies affected by the Covid-19 crisis), Rural Development (CAP), Just Transition Fund (green transition), RescEU (against natural disasters), etc.

The agreement provides for a strengthening of the Recovery and Resilience Facility, designed to mitigate the economic and social impact of the Covid-19 crisis and, at the same time, to face long-term challenges: its total amount increases to 672.5 billion (312.5 billion in grants and 360 in loans).

But the real sore point concerns the Multi-annual Financial Framework, the EU’s seven-year budget, which undergoes slight and symbolic reductions (compared to the February proposal of the President of the European Council), on R&I, SMEs and market surveillance, to balance the increase of the so-called rebates for recipient countries.

A very hard political game has been played on the governance of the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF).

The RRF is conceived as a direct management fund, with a very strict governance in which the European Commission should manage the appropriations to the Member States on the basis of the achievement of the objectives set by the specific national plans, approved by the Commission itself and by a qualified majority of Member States.

The Netherlands firmly opposed this system by declaring that they “do not trust the Commission”, but their request for an intervention of the European Council in the procedure for verifying national plans and for a unanimous vote by governments was legally and politically inadmissible: legally because it was a substantial modification of the powers of the European Council, to the detriment of the Commission and the European Parliament, and this would have required a Treaties changes procedure; politically because it would have given veto power to each Member State, with the risk of blocking disbursing funds process.

Trying to please the Dutch, the President of the European Council Michel proposed the so-called super emergency brake, which effectively allows any country to slow down the disbursement of funds: the Netherlands could now use this system as an electoral weapon, given that prime minister Mark Rutte is aiming for re-election and that the delivery of the first tranche should precisely coincide with the Dutch elections.

The issue raised by the Netherlands in a provocative way, however, is systemic. The alleged Conte-Rutte clash has been a pretext for the latter and for the Austrian Prime Minister Kurz to underline the desire to replace the Franco-German axis with a “hybrid” one, with variable geographies, in which even the little countries can count.

The clash between the Frugal4 and Germany and France has put two visions of Europe and European integration on the scales, where for now the Euro-opportunist seems to have prevailed.

And the countries of the Visegrad block have served to move the needle on this scale.

Especially when it comes to conditionalities.

They opposed conditionality on respect for the rule of law and were satisfied, thanks to the introduction of a series of guarantees (such as the possible closure of the infringement procedure for Hungary and Poland), to prevent them from blowing up the agreement.

They opposed conditionality on climatic targets and were partially satisfied, with further guarantees on allocation criteria for the structural funds as a form of compensation for the strengthening of these objectives.

This is an agreement which, until a few months ago, seemed unthinkable and which today appears historic, despite the various contradictions that emerged and persisted.

Following the motto of Aristide Briand, this agreement can be considered perfect because everyone is unhappy. Everyone has won and everyone has lost, but someone … has lost more.

The European Commission is the big loser of this European Council. Governments have maintained control of the negotiation, modifying its proposals for their own use and consumption.

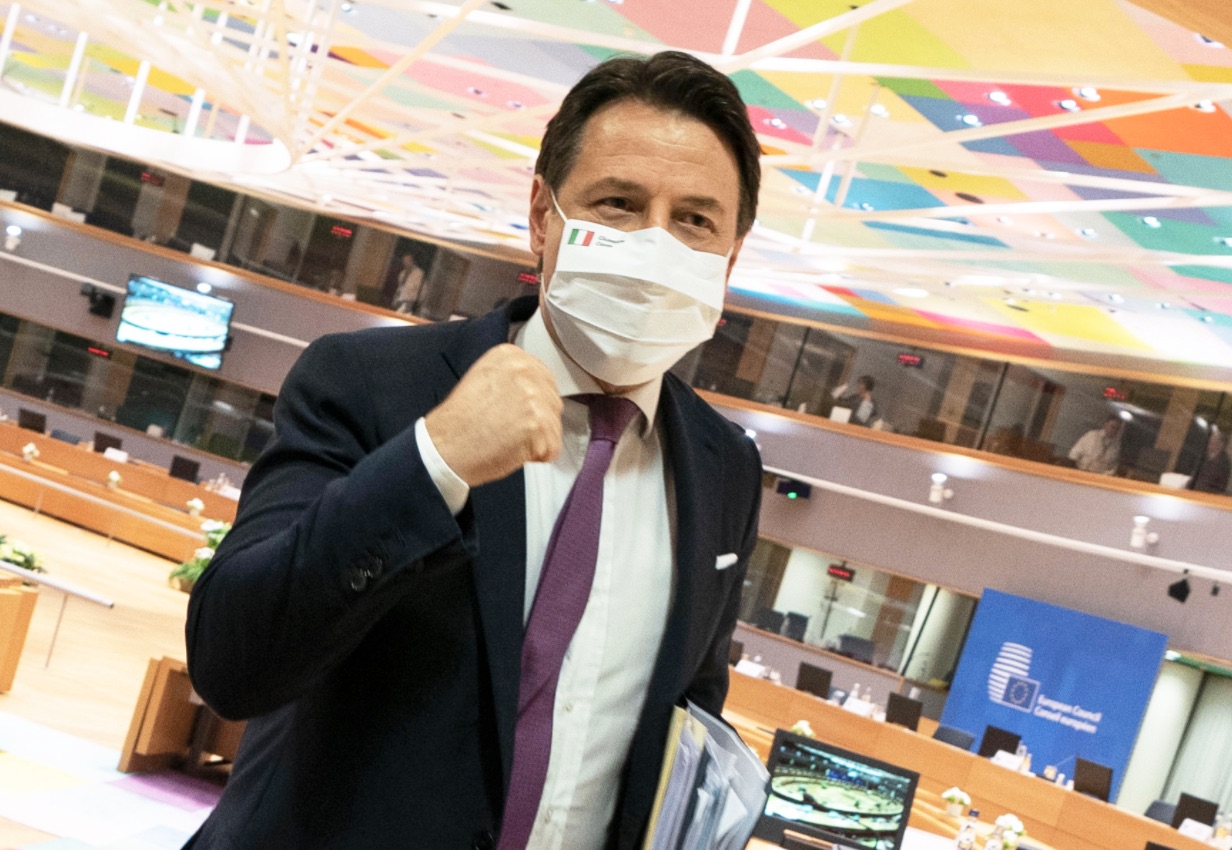

Italy and Spain gained on NextGenerationEU funds, having focused all the negotiations on this aspect, instead leaving out the Multi-annual Financial Framework (on which it will instead be necessary to deepen the evaluation on the benefits and losses).

According to Italian government sources, Italy would now have 208.8 billion euros (81.4 billion as grants and 127.4 million as loans). Compared to the Commission’s May proposal, Italy earns around 34.974 billion (more loans than grants).

As either a twist of fate or of diplomatic mastery: in terms of loans, Mr. Conte takes home the sum of the ESM – on which so far there have been a lot of quarrels at home – but without the ESM control mechanism.

In the eye of the public and of some EU Capitals, the Netherlands and Austria have earned the reputation of “bad boys”, but the Frugal4 – which together represent just over 10% of the population of the Union – managed to influence choices that affect all Europeans: they forced the President of the European Council Michel, the President of the Commission Von der Leyen, Angela Merkel and Emmanuel Macron, to fall below the psychological threshold of 400 billion grants; to close the deal on the governance of the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) they obtained the super emergency brake, increased their rebates on contributions to the European Budget and showed their voters that they know how to cope with the Franco-German axis.

The countries of the Visegrad block bring home successes on the distribution keys of the Cohesion policy (the structural funds) and on guarantees on a soft application of the clause that binds the disbursement of EU funds to the respect of the Rule of Law principle.

The President of the European Council Charles Michel was able as a flexible and indefatigable negotiator (while the Franco-German axis – weakened but not defeated by the Frugal4) of giving a precise direction to the EU integration process through the creation of the core of a true budgetary function, the decision on its own resources (European taxes to finance the multi-annual budget), a common guarantee, and the mutualization of responsibilities, albeit in an atmosphere of great distrust.

Now, in every capital city of the EU the game of “nationalizing the victories and communitarianizing the defeats” of this negotiation will begin and the EU will appear even more intergovernmental, a political organization in which national interests continue to prevail to the detriment of the general interest.