Last night, Massimo Sarti, cultural attaché at the Italian Cultural Institute in NYC hosted Neapolitan writer Angelo Cannavacciuolo and his American translator, Gregory M. Pell, professor of Italian at Hofstra University. They were joined by Alane Salierno Mason, the vice president and executive editor of W. W. Norton and founder of Words Without Borders, and Joseph Luzzi, the Asher B. Edelman Professor of Literature at Bard University and author of many books, including My Two Italies, and, most recently, Botticelli’s Secret.

Cannavacciuolo has crafted a body of work that is highly praised in Italy but not so well-known in the United States. That should change with the translation and publication of this novel, Le cose accadono, as When Things Happen, by Rutgers University Press’s new series OVOI, Other Voices of Italy: Italian and Transnational Texts in Translation. This is a cultural initiative that is as welcome as it is necessary. It now gives English readers an opportunity to read one of Italy’s leading contemporary writers.

The Italian edition was published to glowing reviews. La Repubblica noted Cannavacciuolo has created “a whole universe governed by the iron law of truth.” Il Mattino wrote that “Cannavacciuolo’s narrative engine is marked by his obsession with the presence of suffering in the world and by the moral obligation to portray it – to translate it into words.” For Il Manifesto, this is an “incandescent book that offers a ruthless examination of the same Neapolitan reality in which it directly participates.”

Protagonist Michele Campo has managed by force of will, a difficult marriage to Costanza, and fortuitous circumstances, to escape the working-class environs of Naples. But a chance (or foreordained) encounter with a strange child in the foster care system of the city will force his career and very existence into crisis.

Cannavacciuolo opened the evening reading with an excerpt from the original Italian, in which the protagonist, a speech pathologist, reflects on the strange trajectory of his life, from the working-class quarters of Naples (and the shame of his scarpe bucate), to the rarified precincts of wealth and culture, first when his father becomes doorman to an elegant apartment house in the Vomero district, and then in his relationship with Costanza, who has always lived in that world.

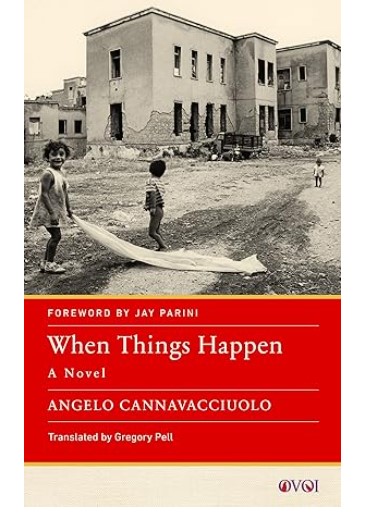

Themes of class, identity, culture, and violence were the thread of the discussion for the evening. Beginning with Mimmo Jodice’s searing photo of three children in a squalid and degraded neighborhood for the cover. But look closely and you will see a radiant smile from the young girl. A visual contradiction that is mirrored in the novel.

Translator Pell posed and answered the question of, “Why translate and publish this particular novel of Cannavacciuolo?” For Pell, the original Italian text is “touchingly sublime, yet realistic,” full of invented metaphors that required a collaborative effort with the author to translate accurately. Pell read an extraordinary excerpt from his translation in which Michele Campo recounts the sensual and psychological pleasure in crafting a pair of trousers from a bolt of linen under the tutelage of his mother. The English text successfully captures the different linguistic and psychological registers of the protagonists and their social setting.

Alane Salierno Mason recalled her own personal history, with her father’s family from Salerno, and his insistence on the proper pronunciation of the family surname. She and Joe Luzzi noted the depictions of culture between the classes in Naples in the book and how Michele Campo aspires to the world of cultural capital for the status it would bring him, not for its intrinsic worth. Cannavacciuolo remarked how the novel was in some sense a story of family origins in general but also autobiographical. This begins with a consciousness that one doesn’t have the necessary “tools” for life but that “one could build your tools by yourself to change your reality.”

And it is a harsh reality. Cannavacciuolo does not shy away from brutal depictions of shattered families and shattered neighborhoods, each continually reproducing the other. Pell noted the title is an existential reality but also an imperative. Cannavacciuolo insisted “I’m convinced things happen and our will is to change our lives.” Michele is at first resigned to his life, but a chance encounter with 5-year-old Martina, who requires his expertise as a speech pathologist, changes his life. She also represents the danger of pulling Michele back into the former life he seemingly has successfully left behind. And indeed, the dénouement ties Michele to Martina, not by his and Costanza’s attempt to adopt the girl, but in an even more fundamental way.

Discussion with the audience turned to the seemingly never-changing nature of the city. Cannavacciuolo pointed out that although the story unfolds in 2005 (the original Italian was published in 2008), the social pathologies are still current. (He gave three disturbing examples, ripped from headlines.) Salierno Mason noted, for example, how the terremotati (those displaced by the 1980 earthquake) were still living in “temporary” housing a decade later.

When Luzzi asked Cannavacciuolo about his relation to the city of Naples, the author replied that it was both concrete and ambiguous. “You can create another Naples,” Cannavacciuolo told the audience. “There are as many Naples as you can create.”