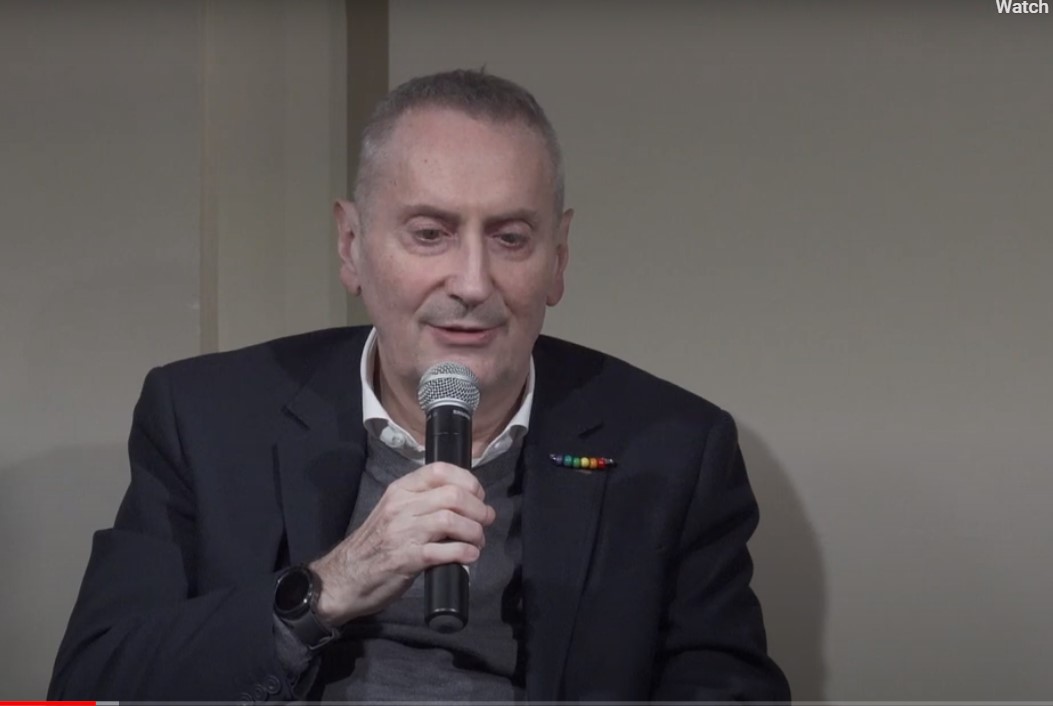

Franco Grillini hardly looks or sounds like a revolutionary firebrand. But Grillini, 68, has been one of Italy’s most prominent radicals for forty years, a gay rights and leftist activist working outside and, as a member of parliament, inside the Italian state. Grillini is the subject of a recent documentary film, Let’s Kiss: Franco Grillini, The Story of a Gentle Revolution. The film, which won Italy’s Nastro d’argento award in 2022 for best documentary, was screened on April 17 at Casa Italiana in New York. Grillini, along with the film’s director, Filippo Vendemmiati, attended the screening and spoke about the film, his political activism, and the current state of Italy’s gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender movement.

Written by Vendemmiati, a longtime friend of Grillini’s, and his wife, Donata Zanotti, Let’s Kiss is loosely based on Grillini’s book Ecce Omo. The film incorporates interviews with Grillini and footage from his many media and public appearances over the decades. At eighty-five minutes, it is a compact account that is always engaging and often moving. But it also too often skims the surface of Grillini’s remarkable life.

Let’s Kiss begins with his childhood; he was born in 1955 in Pianoro, a town near Bologna, his parents proletarianized former peasants. The film touches on his early years as a communist militant, his coming out as gay, his central role in forming Italy’s major gay rights organization, Arcigay, the AIDS epidemic, his years as a parliamentarian, and his current status as an eminence grise who remains politically active. Grillini, who graduated from university with a degree in education, seems more like a professor than a militant; throughout the film, he is a serene, appealing presence. There is no narrator and no interviews with anyone other than Grillini. That he comes through directly and unmediated is the film’s strength but also its weakness; a narration could have provided greater detail and context. This limitation is particularly evident in the treatment of Grillini’s political career, which was more substantial than the film lets on.

Grillini notes that in the ‘80s, there was a “complicated” relationship between Italy’s gay movement and the Communist Party, which hadn’t integrated sexuality into its class-based politics. In a film clip, Grillini tells an audience of nonplussed factory workers that there indeed are gay people among their ranks. What’s not mentioned is that Grillini entered politics in the 1970s as a member of the far-left Proletarian Unity Party. (He also was a journalist, which is briefly noted.) He ran for political office in 1985 as an Italian Communist Party candidate in the Bologna province. He was elected to the Bologna provincial council in 1990 and re-elected twice. After the Communist Party dissolved in 1991, he joined the Democratic Party of the Left and was elected to the Italian parliament in 2001 and re-elected in 2006.

There had been a gay movement in Italy during the 1970s—the film includes footage of a 1978 rally—but it was small, limited to a few cities, mainly in the north. Grillini, who had heterosexual relationships and, at one point, was engaged to a woman, was a late bloomer as a gay man and activist. He didn’t come out until 1982, but he made up for lost time. That year, Grillini helped found the Circolo Omosessuale Ventotto Giugno in Bologna; in 1985, the Circolo evolved into Arcigay, Italy’s national gay organization. Grillini became president of Arcigay in 1987; a year later, he called a special session to recognize the presence of lesbians in what then was a male-dominated organization. The Bologna-based movement grew to the point that the city became known as Italy’s gay capital. Still, the movement was hindered by societal homophobia and the fear of most gay and lesbian people to be publicly identified. In the film, Grillini remarks that even now, most gay people in Italy live a “hidden life” and “still have to lie” because Italy is “sexophobic” and hypocritical about sex.

Grillini’s coming out coincided with the beginning of the AIDS epidemic; as in the United States, public officials in Italy ignored or denied the seriousness of the issue, while the Vatican and political conservatives stigmatized people with AIDS and opposed condom use to curb HIV transmission. (The government’s AIDS campaigns didn’t mention condoms until 2007.) In the mid-‘80s, Carlo Donat-Cattin, the Christian Democrat health minister in Bettino Craxi’s administration, opposed condoms and rejected sex education campaigns in schools, claiming they would encourage anal sex. He refused to speak to gay organizations and declared, “Only people who go looking for it catch AIDS.” The film includes a clip of Grillini taking on the homophobic minister, with irony and cutting wit.

Arcigay distributed condoms publicly in Bologna before the militant activist group ACT UP, a point of pride for Grillini. He says that from 1983 to 1996, he went to many funerals. “I wonder how we made it through that period,” he somberly remarks.

Let’s Kiss moves between Italy and New York, with footage of Grillini at the Stonewall 50–World Pride NYC celebration in 2019. Grillini joined the Arcigay contingent at Stonewall 50 but didn’t march. He participated in a wheelchair because of a life-altering crisis in 2016, when he was diagnosed with multiple myeloma, a cancer affecting plasma cells. Although the disease is incurable, Grillini has benefited from an experimental protocol and is now in remission. He has mobility problems but gets around with a cane these days. Filippo Vendemmiati remarked that when production was about to begin on Let’s Kiss, Grillini stressed that he didn’t have much time. “Now,” the director happily noted, “he’s much better than when we started this project.”

In the film, Grillini expresses the hope that his work “will be useful to the next generations.” He “can’t stand to hear, from gay activists and straight people, that nothing has changed.” Italy’s LGBT movement has won civil unions (the law grants most marriage rights, except adoption, to same-sex couples), but attempts to enact comprehensive LGBT protections have repeatedly stalled. Grillini told the audience at Casa Italiana that the state of the movement in Italy is precarious, with the community under attack by what he called the “para-fascist” government headed by Giorgia Meloni. The Right currently pursues two main lines of attack: demonizing transgender people and what conservatives and the supposedly liberal Pope Francis call “gender ideology” and opposing gay couples having children through surrogacy, a practice the Right condemns as “wombs for rent.”

One hopeful sign Grillini mentioned was the recent election of Elly Schlein as the secretary of the Democratic Party. Schlein, who is partnered with a woman, is the Democratic Party’s first woman and LGBT leader and, at thirty-seven, its youngest. An outspoken leftist who has been compared to the American democratic socialist politician Alexandria Ocasio- Cortez, Schlein doesn’t shy from taking on Italy’s conservatives. At the start of her electoral campaign, Giorgia Meloni proclaimed her social conservative bona fides: “I am Giorgia, I am a woman, I am a mother, I am Italian, I am a Christian.” Grillini quoted Schlein’s response: “I am a woman. I love another woman, and I am not a mother, but I am no less a woman for this.” When the audience cheered, Grillini, smiling, said he would contact Schlein to tell her that her reply to Meloni had an audience cheering in New York.