**/***** (two stars out of five)

Of all his plays, Shakespeare’s histories tend to be the most inaccessible and less compelling for those who are not intimately familiar with the canon. That notwithstanding, a couple of those works have become fan favorites, notably Henry V and Henry IV Part I (which introduces the beloved Falstaff). And Richard III, despite its complexity and exhaustive length, is recognized as one of the greatest pieces of theater ever conceived. So, it is understandable that fans could barely contain themselves when it was announced that The Public Theater’s iconic Shakespeare in the Park at the Delacorte in Central Park would kick off its season with a production of Richard III starring none other than the beloved Danai Gurira (best known for her enigmatic role as Michonne in the hit AMC TV series “The Walking Dead”). O, were it able to live up to even a fraction of that enthusiasm! (Spoiler: it doesn’t come close.)

As one of Shakespeare’s earlier plays, Richard III relies on a great deal of bloody action and melodramatic displays of evil. Richard comes right out and tells us how hideous and despicable he is. “Cheated of feature by dissembling nature/ deformed, unfinished . . . that dogs bark at me as I halt by them,” he tells us, implying that this is his excuse for being “false and treacherous,” as he goes on to reveal his plot to murder his own brother as well as many, many others so that he might wear the crown. With one of his few deft moves of the production, director Robert O’Hara starts the play with a late scene from its predecessor, Henry VI, Part III, in which Richard viciously murders King Henry VI, stabbing him repeatedly, relishing the endeavor. An auspicious beginning that promises fast-moving, slasher film-style murder and mayhem.

Sadly, that promising pace disappears almost as quickly as it arrives, and the breakdown of O’Hara’s disappointing production begins to reveal itself just a couple scenes later. Most notably when Henry VI’s enraged daughter-in-law, Lady Anne confronts Richard, who interrupts Henry’s sparsely attended funeral procession. The usually excellent Ali Stroker (who won a Tony in 2019 for her delightful Ado Annie in Oklahoma!), doesn’t appear to have the proper training for Shakespeare, and her Lady Anne seems more suited for a college production, her line readings having the sing-song-y cadence of someone who hasn’t been properly trained to perform Shakespeare. When she argues with Richard and spits in his face, it comes off more as a Kate/Petruchio spat than the seething rage of, say, Titus Andronicus’s Tamora, bent on revenge for her son’s murder.

Apart from Robert O’Hara appearing to have no directorial facility with Shakespeare—his 2018 Henry V with the Public’s otherwise excellent Mobile Unit could only be described as excruciating—he has proven both a strong playwright (2015’s excellent Barbecue) and capable director (having turned the dull and poorly constructed Slave Play into something of a blockbuster). In Richard III he’s immediately hobbled by a series of very poor casting choices. In a recent interview with NPR, O’Hara revealed that while he didn’t want Richard played as “disabled” (despite his being clearly and repeatedly described as such in the text) he was struck with the idea of “open[ing] the entire play . .. to disabled actors . . . Any actor can play any of these parts.” True, and that sort of openness has created great theater in recent years. Stroker is wheelchair bound; fellow actor Gregg Mozgala (King Edward IV) has cerebral palsy; and the Duchess of York is played by Monique Holt, a deaf actress who signs her lines to one of several actors who appear to know ASL, and relevant lines are repeated by an aide (at which point the play’s momentum grinds to a halt—perhaps supertitles might have solved this conundrum).

These casting choices truly reflect the spirit of the Public Theater’s historic dedication to integration and inclusiveness. It was founder Joseph Papp who cast the [soon-to-be] legendary James Earl Jones as King Lear in 1974 when Black actors were simply not being considered for such roles. But inclusive casting does not necessarily lead to great acting, and there is no James Earl Jones, Raul Julia or Morgan Freeman in this play. Great acting stands on its own, and is generally aided only by great directing. And in Richard III one might look more cynically at O’Hara’s bending over backwards so far to cast “disabled” actors, rather than focus on skill and appropriateness for the role.

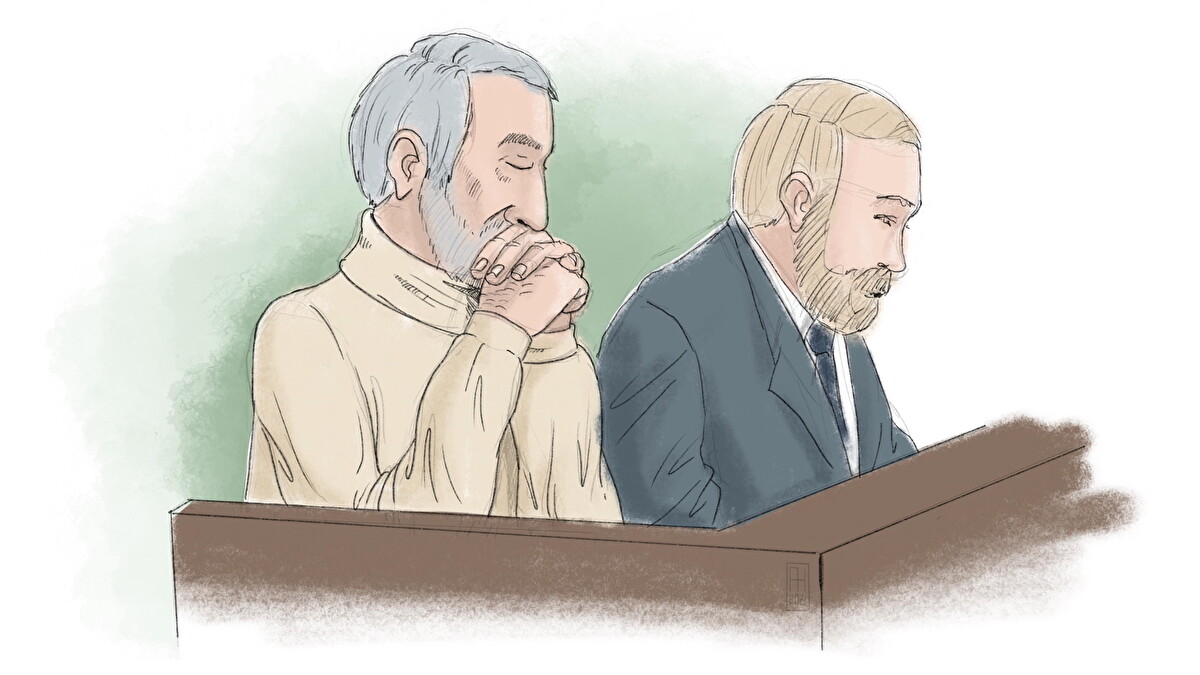

This isn’t to say that there are not a handful of quality performances, existing on their own island within the play. Despite her tremendous acting skills, Gurira’s Richard comes off as more of a silver-tongued and deadly bureaucrat than the Machiavellian cutthroat he actually is. She is less a terrifying Pol Pot (who committed genocide openly and indiscriminately) and more Francisco Franco (who smiled and played the statesman while secretly enabling his Guardia Civil and other confederates to slaughter “enemies” by the thousands). But that’s not the Richard we know and love to loathe. And it’s less interesting to watch on stage. O’Hara seems to feel that having Richard played by a woman changes perspective, which it simply doesn’t. Gender-swapping is nothing new in Shakespeare and rarely does it significantly change the story or meaning. It generally comes down to the power of the actor’s portrayal and gender is practically immaterial.

In addition to Gurira’s fine, if misguided, performance, Daniel J. Watts’ Catesby Ratcliffe is a wonderful toadie to Richard; Michael Potts, as always, is a reserved and noble Lord Stanley; and Sharon Washington’s doomsaying Queen Margaret is utterly wonderful, but likely a mystery to those not intimately familiar with the text, as her character seems to float about the circumference of the play. Direction, once again, is to blame.

It’s a pity the key elements of the play are so lacking, for the production design itself is magnificent. Myung Hee Cho’s beautiful set of long, narrow gothic arches (almost resembling portions of canoes set on their ends) gorgeously lit in variable colors from within (Alex Jainchill) and Dede Ayite’s stunning period (or possibly Tudor, with occasional touches of modernity thrown in) costumes set the stage for what could have been a dramatic and entertaining night of theater.

Nonetheless, Shakespeare in the Park remains a meaningful and iconic part of a New York summer, so there are those who enjoy the productions no matter their quality. The evening I attended, it was a beautiful day in the park and people were clearly excited to return to normal life and sit in a theater without being required to wear a mask. But about 20 minutes into the play I noticed something I had never witnessed at a Shakespeare in the Park performance. Audience members (some of whom had likely waited in line for hours for their free ticket) began quietly leaving the theater. Not just one or two, but dozens. And after intermission the theater emptied even more. This is not supposed to happen in New York’s beloved Shakespeare in the Park, but one could hardly blame those who’d rather have been anywhere else at that moment.

Richard III. Through July 17 at Central Park’s Delacorte Theater (enter from Central Park West at West 81st Street). www.publictheater.org

Photos: Joan Marcus