Joseph Sciorra, author of the 2015 monograph Built with Faith: Italian American Imagination and Catholic Material Culture in New York City, is a storyteller, a folklorist by trade. His book begins and ends with a story, and features many throughout, as if to cede his acquired wisdom to those characters within them. I will thus begin in the same way: Gino Vitale emigrated to New York in 1977 at age five from Sicily. Now, as the president of a development company, he is one of the forces promoting and profiting from the gentrification of the Brooklyn neighborhoods of Red Hook and Carroll Gardens. A typical story with a twist: he inserts arcuated niches with Catholic statuary in the facades of all his buildings. As he explains it: “You know, we’re religious people. It’s like the house is blessed.”

Sciorra has spent more than 35 years “in the field” of New York City researching and experiencing Catholic Italian American vernacular art. Stefano Albertini of NYU’s Casa Italiana, where the book was presented, called him one of today’s few “militant intellectuals.” Sciorra is interested in how New York City’s Italian American Catholics have creatively appropriated those areas of the city in which they live, proclaiming them their home through the additions and enhancements of the built environment around them. Such additions include grottos, altars, nativity scenes, Christmas house displays, neighborhood processions, and more. Most importantly, he is at pains to emphasize that these appropriations have a layered and very dynamic relationship with the present moment and place, alongside their relationship with memories and imaginations of the faraway past, which however never take the form of passive nostalgia.

Sciorra has spent more than 35 years “in the field” of New York City researching and experiencing Catholic Italian American vernacular art. Stefano Albertini of NYU’s Casa Italiana, where the book was presented, called him one of today’s few “militant intellectuals.” Sciorra is interested in how New York City’s Italian American Catholics have creatively appropriated those areas of the city in which they live, proclaiming them their home through the additions and enhancements of the built environment around them. Such additions include grottos, altars, nativity scenes, Christmas house displays, neighborhood processions, and more. Most importantly, he is at pains to emphasize that these appropriations have a layered and very dynamic relationship with the present moment and place, alongside their relationship with memories and imaginations of the faraway past, which however never take the form of passive nostalgia.

Sciorra is trained as an anthropologist, and his approach demonstrates this. He believes in the necessity of experience and interaction with the “subjects” of his interest – the necessity of ethnography, participant observation, strategies that have very rarely been used in the field of Catholic art. Sciorra explains that the “burden of elite art,” which can easily be found in the Catholic tradition, has resulted in scholars’ focus on aesthetics and symbols at the expense of lived and vernacular forms of creativity. Layers upon layers of images of the saints and other holy figures, mixed with objects such as stuffed animals, as in the case of Joseph Pezza’s shed, are often dismissed with terms such as “kitsch” or “unofficial,” rather than being considered deserved objects of beauty and study in of themselves. A member of the audience at the book presentation claimed that the devotional creativity of the Italian Americans studied did not really qualify as art because when they would look at their own shrine to the Madonna, for example, they would see the Madonna, not a work of art. Elite cultural production for decades now has, indeed, perhaps only been identifiable through its own self-identification as art – however that should not stop us from giving art a wider, perhaps more organic, territory, as Tolstoy does in this particular quote referenced by Sciorra: “life is filled with … art of various kinds, from lullabies, jokes, mimicry, home decoration, clothing, utensils, to church services and solemn processions.”

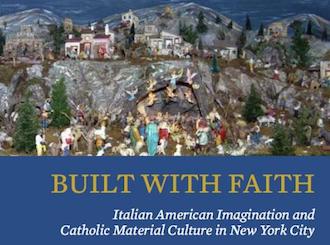

Sciorra’s perspective comes from his deep engagement with his theme: he has assembled his own presepio (Nativity creche), for example, in order to better understand the motivations and emotions that emerge from it. Importantly, Sciorra places material culture at the center of his analysis and conclusions. The attention to material culture, which regards objects as carriers, symbols, and producers of culture and meaning, has enabled several things. For one, it has allowed Sciorra to identify a style particular to Italian Americans. Sciorra uses Dick Hebdige’s definition of style, as “the process whereby objects are made to mean and mean again,” and he then defines the elements of Italian American style according to him: a respect for crafts and skills done well, the inclusion of concrete and stonework, the enjoyment of accretion and the interplay of contrasts, the appreciation of exuberance and festivity, and the inclusion of the human figure. “More is better,” is another way Sciorra describes it, visible, for instance, in the image below, where instead of one image of Our Lady of the Snow, there are eight hanging all over each other. In more modernized examples, Dyker Heights is alight around Christmas as some inhabitants swamp their houses with Christmas lights.

The material culture of Catholic Italian Americans also plays a role as an anchor for the community, both the local one and the wider “paese-affiliated ethnoscape of global piety.” Altars, such as Angela Rizzi’s magnificent one donned with vases of cut flowers and loaves of blessed bread in Sheepshead Bay, became gathering points for the local community, with neighbors and guests, both Italian American and otherwise, appearing only when the presepi, altars, or other devotional pieces are installed. The objects, the art, enable the sociality. On a larger scale, practicing Catholics of the Italian diaspora, who are dispersed from Canada and Brazil to Australia, feel a sense of community when they visit each other and are able to partake in similar festive processions dedicated to similar saints.

Most importantly, however, according to Sciorra, is how physical manifestations of Italian American’s Catholic devotion function as the “embodiment of the sacred” in their daily lives and built environment. They are not mere decoration, tradition, or even lived creativity – they are sacred presences that can be prayed to, that enable miracles in the lives of their many creators. Such a view and embodiment of Italian traditions were revived after World War II, when an influx of working-class Italian immigrants stabilized and redefined New York City’s Italian American community and its relationship with Catholicism and religious expression. As Gino Vitale said in respect to the miraculous occurrences in his life, “I could tell you a hundred stories.” This is why all the actors in Sciorra’s book identify as Catholics – it is important that they are enacting their devotion in part through the material culture they create.

Sciorra is an engaging and accessible speaker and writer. He is erudite and non-judgmental, allowing people and their stories to have the space to justify themselves. The book is simultaneously an intimate portrayal of a relatively small community engaging in personalized acts of creativity and religious devotion, and also a wider analysis of the vernacular motivations behind the changes in and meanings of urban landscapes. We are accompanied throughout the book with engaging stories of genuine individuals emerging from the particular context of Italian heritage, New York upbringing, Catholic religiosity, and changing urban dynamics.

Sciorra’s research, and specifically the presepi he studies, were just featured in a New York Times article. This attention is in many ways a positive sign for the scholar and his work, evidencing that it is being appreciated and sought out. We may want to ask ourselves, however, how much the mainstream chronicling of and attention to such “cultural” activities contributes to their advancement, and how much threatens their dynamism instead. Sciorra speaks of the relatively new “gentrifying gaze” at long-practiced processions that threaten to change the nature of the events from a chance to engage with the neighborhood to a piece of rehearsed theater for external onlookers. Could these onlookers, with their appetite for the exotic and their tendency to take photographs, be a force that fixes in place the currently active Italian American traditions in New York? This may be a question for future research, or observation. Gino Vitale, with whom I started, is spreading his understanding of Catholic tradition through gentrification. This example reveals how necessarily complex any understanding of Italian Americans and their religious and cultural understandings of themselves in space must be. Sciorra’s personal and thorough approach encourages us to apply such a complex understanding to any group and its own unique attempts to come to terms with its current time and place.