They say I lived in Italy until I was four, in the farmland around a small village called Vallemaio. When I recall Vallemaio, the macere always materialize first, those hand-made dry rock terraces found all over the Mediterranean. They say I ran along the macere ever since I could walk, and stomped around the soil and the tops of the rock walls against all the efforts of my young aunts to keep me away from the sheer edges. I played in the dirt, chasing chickens, putting everything in my mouth, low hanging grapes, plum tomatoes, apricots, lots of figs, and the occasional insect. Then my brilliant brother was born in a stone house in the valley. Then my mother took me to l’ameriga and the long process of forgetting began.

Over the years, memories of Vallemaio softened and nearly dissolved, but the macere survived, a fretwork for my imagination, along which sounds and images play. Things along the macere come into view but I can never predict when or how. Sometimes I see materialize the trees, the olive, apricot, plum, and pear planted along the edges, the grape vines looping in between, and clusters of green translucent fruit hanging like lanterns. At times there are figures along the macere, men in vests and baggy pants, and women with the headscarves and stiff canvas skirts of the ciociara culture of latter days, chatting, stooping down to plant, to scythe, or climbing up to pick fruit and prune. The dusky orange sun lights their hair, makes their ruddy brown cheeks shimmer darkly. Before World War II, the ciociara women had been better known in Italian literature and lore, and the subject of hundreds of Romantic-era paintings and poems. To depict certain atrocities during the war, Alberto Moravia wrote his great wartime novel La Ciociara, a title that was immediately recognizable in Western Europe. There was the film by Vittorio DeSica with Sophia Loren, which is known in the States as Two Women. Being the son and grandson of ciociara women, and a former toddler among the macere, I can say that the people of Vallemaio, right in heart of the old ciociara region stretching from around Rome to just north of Naples, have a substance and vigor that takes time to get a feel for. The movie, and Loren, are great, though.

When my mother and I came to the United States, we shifted between the Italian-American enclaves of those days, Corning, Camden, Bensonhurst, Saugerties – wherever there were cousins in other words – and then we settled in Coney Island in our own place, a grand, leaning three-story wooden structure that used to be a boarding house. Then my vigorous sister was born. At the age of ten, I gradually mastered this new terrain, the ghetto Coney Island of 1970s New York, burned out houses on every block, gangs of all stripes, and mazes of fences everywhere, by the huge subway terminal yards, along abandoned parking lots, around the school basketball courts, and behind everyone’s back yard. These were the macere now for me. With my scruffy friends, I climbed over them, slipped under them, negotiated barbed wire when necessary.

The whole neighborhood was our playground. We marked the street with paint we “found” at the yards and, like the Brooklyn kids we were, we played skelly, punch ball, touch football, and stick ball right there on the asphalt. We moved to the side when the rickety B60 bus came through. Skelly was especially fun but treacherous, because you had to crouch over your wax-filled bottle cap as you aimed for the numbered boxes, so you might not see the bus right away. We ranged far and wide, too. In the stinking slime of Coney Island Creek we caught horseshoe crabs. They say that in the times of the Revolution, the Creek used to separate the “Island” from Brooklyn, but now it just sputtered along behind the factories, the car repair garages, and the Pathmark supermarket, full of dumped oil, rusted machines, and some chemical brew. I liked imagining Coney Island one hundred, two hundred, even four hundred years ago when it was given its name by the Italian explorer, Giovanni da Verrazzano, “Island of Rabbits.” When I was growing up there were still wild rabbits on the northwestern side of Coney Island, and I’ve heard they are still there today. The Creek ends at the highway, and on the other side is Sheepshead Bay, the deepwater harbor where fishing boats leave for Long Island Sound around dawn. On the gaudy south side of Coney, we played in the damp, deep sand under the boardwalk, went on the Wonder Wheel or Cyclone roller coaster for free if someone’s uncle was running the booth, and ran along the glorious stretches of Atlantic surf, the only thing in our neighborhood clear of garbage, rubble, bricks, and weeds.

My sense of being of Vallemaio eroded bit by bit, a bit by the child’s fierce love of the now, a bit by my Brooklyn playmates, whose families had left Italy behind long before we did, and the biggest bit by my parents, who were ashamed of their origins and avoided speaking Italian at home, let alone dialect. But then a miracle – my grandparents came to live with us. My grandfather, who had been a farmer and landowner for much of his life, immediately started working at low-paying jobs. He worked by day at a machining and plating factory, and by night as a dishwasher. My grandmother babysat us while my mother waitressed all week. My grandmother never gave up the headscarf and knee-length skirts of the ciociare, and she defended me as necessary in that tough neighborhood. At 11 years of age I began working, too, first in the gold-plating department of the factory, and then as a butcher’s delivery boy, and later for a TV and air conditioner repairman. I dutifully and proudly contributed cash to the family every week – sometimes as much as $30. My grandparents had brought aid and solace, and some desperately needed income, but for me they had brought a bigger treasure, the dialect of their town, in which I found (and still find) endless delight.

I understand my parents’ avoidance of Italian now. There was a double stigma for them, one imposed by the nation of Italy, desperate to leave behind its agrarian and fascist past, and one by our new country, where the settling of waves of immigrants was unsettling to others who had come before us. Being from the South in Italy meant you were tainted with associations of poverty, backwardness, and hints of racial inferiority. On the other hand, in the United States we were subject to the lingering prejudice against “wops,” and associations of organized crime, tawdry clothing, and some vague implication of swarthy sneakiness.

Later in the twentieth century, popular American conceptions of Italy and Italians shaded into more benevolent forms of stereotyping – land of the Renaissance, land of glorious food, romance, and wine, and a neat place to bring the kids. None of these by the way corresponded to the reality of Vallemaio, nor to the thousands of small Southern Italian villages where most Italian-Americans can trace their ancestry. Still, Italian-Americans benefited from the shift in attitudes; we had something called “passion” and the cute habit of speaking with our hands. The Italian accent is still mimicked in a sort of good-natured way, and many Italian-Americans play along. But what had been nearly wiped out in the meantime was something that was neither high culture, nor the generic images of the family-loving, hugging, food-crazed immigrant dynasties. What was almost completely lost, though, was something special, and much more fragile, the culture of the Southern mountain villages, their unique languages and wit, and most of all the toughness and resourcefulness of the prewar generation. Growing up in Coney Island, and on occasion visiting my great grandfather in New Jersey, I knew nothing of this history, and my family wasn’t all that forthcoming in explaining it to me – or, more likely, I didn’t have ears to hear. But there was a deeper yearning I was barely conscious of, until one day I decided to go see for myself. When I returned Italy at the age of 19, I sensed there was so much more to know, and I came with a huge hunger.

First, I saw the great cities of Italy, the great sights, with my untiring and brilliant uncle Luigino, who dressed impeccably, and drove an Alfa Romeo. He could also read Latin and explain the history behind the incredible architecture we saw everywhere. At home, in the town of Cassino, I was welcomed by his wife, my aunt Angelarosa, the sister of my tough immigrant mother. That summer, I realized there were two main branches in my family there in Italy, those who embraced the new Italy, modern, chic, educated, and classy, and those who lived more or less in the old style. I finally made my way up into the hills of Vallemaio, which the villagers called by its old Norman name. It was then I remembered my grandfather in Coney Island saying, “sono vallefreddano,” I am of Vallefredda. As I approached the “cool” valley among the hills, I smelled the woodsmoke, and passed a carozzella, one of the very few painted horsecarts still on the road in those days. The new Italy faded behind me, and I found my appetite for Vallefredda desperately, desperately sharp. I stepped out of the car amidst the macere of my great uncle’s farm, the wiry ancient, Zio Ferdinando. My well-dressed cousin sped away in his own Alfa Romeo. The sound of shifting gears faded along the curves of the road that descended towards Cassino.

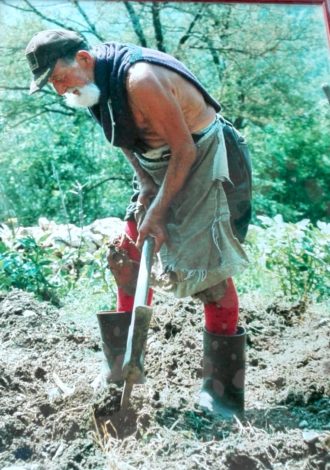

Zio Ferdinando immediately enlisted me into a completely different rhythm of life, which challenged my body and mind more than anything I have ever experienced. He put me to work carrying pails of water up the slopes, hauling steaming manure, pruning olive trees, tending cows deep into the evening, and scything grass crouched low to the ground. It seemed to me like I was always hauling manure. But that was just the first week, building callouses on my hands, and scar tissue up and down my legs from the bushes and sharp rocks of the macere, and in the meantime hearing stories of the village, the family, and the war, and memories of memories until we were lost somewhere in the 19th century and beyond.

Zio Ferdinando’s stories had a sense of forever to them, and each tale felt absolutely necessary to me. I heard of the roaming briganti of the late 19th century, those sandbaggers and thieves who frightened the inland villages in the chaotic and sometimes lawless period after the Unification of 1865. I heard of the crafts and technologies of subsistence, such as scraping grains of sugar from drying figs, but most of all I learned about the characters and lifestyles of Vallemaio before la Guerra, the great war. There was Michele, born before Unification, a distant uncle of mine, who was arrested and sent to prison in Gaeta, which was then in the Papal States. My Coney Island mind tried to grasp this phrase, “papal states,” a country run by a pope. At that time, the southern border of the Papal States was 30 kilometers from our land. Michele came back in 1860 or so, reading and writing in Italian and able to make shoes. There was my great-grandfather who would fearlessly meet wanderers on the road and get them to work on the land for a week. Their payment? Food and accordion music. Through Ferdinando’s words, I felt rooted, and connected to a group of people who were physically strong and funny. And Ferdinando never just told a story – he yelled it, and I can still hear his voice whenever I want. On the 6 train during a New York City rush hour, pressed against other sweaty New Yorkers, I can close my eyes and there it is, Ferdinando’s lusty mountain holler in the open air. Ferdinando’s tales, heavily marked with shouts, imitated accents (which he was so good at), and extravagant details opened a vista for me. In school and in my many solitary hours in libraries all over Brooklyn, I had read about “peasants,” “farmers,” “villagers,” but these words were hollow, and no matter how I tried to grasp the drama of history, I had no handhold. Now there was this brilliant medium between me and the past, this man, this cyclone of pure energy and passionate recollection. He offered me history and hard work. This was the formula I’d been missing.

And I continued to work, from the earliest morning to just before midnight, barely keeping pace. I pruned olives, bathed the sheep, collected hay by hand, and brought the cows down into the dark valley at night. I had never done this work before. He just threw me into the work, and I learned through my senses and muscles first, and only then through my mind. When I scooped and scraped the manure out of the cow barn, Ferdinando was there by my side, talking, always working and talking, this time about the Romans. Romans loved manure, he said, because their Empire depended on farmers, and farmers needed to fertilize their fields. They used to call it l’oro romano, Roman gold, said Ferdinando. “Enough. Now shovel it into that wheelbarrow there and haul it down the hill and dump it where I showed you, Fiore.”

There could have been no passing down of any knowledge without the physical work. I found this to be true in later years, when I spent time with other women and men of Vallemaio. If you just talked, you learned little, but if you worked alongside them, you learned everything, and a forgotten world would start coming into view.

At Ferdinando’s house I was given a room on the second floor to sleep in. The room was painted eggshell blue up to your chest and then a papyrus white the rest of the way up. My mattress was so old it was basically a huge doughy pillow. The sheets were gray and smelled of oak. The window frame was two feet deep. Two slatted shutters swung out, hinged onto the outside wall, painted dark green and peeling graciously. When I opened these for the first time, there was Monte Calvo, taking up three quarters of the frame and a high, turquoise sky above, wisps of clouds. The night fell gently. Somewhere in the house Zio Ferdinando was sleeping the sleep of the strong, as the English poet John Milton says. My aunt, Zia Dosolina, was in her fragile sleep on the old sofa in front of the fireplace, and my cousins Adriana and Silvana were somewhere, too, breathing in the air of the valley. I had come very far from Coney Island. In a world patrolled by bullies, you can get your occasional and delicious revenge, but there’s always the next challenger. And no one had to tell me how to be Italian, what kind of Italian to be. Here in ancient Vallefredda, I had found a new way to be powerful, and to build the roots of memory day by day. A rusty bell tinkled in the night. That was the ram on the slope behind us, among the flock settling to sleep on the grassy terraces of the macere. The sweet breeze came in through the window, along with the smell of wild sage and maybe a whiff of chicken poop. My eyes closed. I was home.