Every morning millions of people reach for their eyeglasses even before getting out of bed. With the world in focus, their day can begin. Nonetheless the history of eyeglasses remains blurry even if with a strong Italian connection from Ancient Rome to this day.

So, it’s no wonder a feature article, “The Power of Big Ideas” published in Newsweek on January 11, 1999, reported that reading glasses, Gutenberg’s printing press, and the atomic bomb, had changed the course of history more than all inventions during the last 2,000 years. Of course, that was before the internet.

Seneca, the Roman statesman, orator and tragedy writer (4 BC-65 AD), wrote that “thin, muddled writing looks larger and clearer through a glass bowl full of water”. The historian Pliny the Younger 62-113 AD) reported that the blue-eyed Emperor Nero watched games at the Circus Maximus through an emerald monocle.

A millennium later the British philosopher and scientist and Franciscan friar Roger Bacon (ca. 1214-94) in his Opus Majus asserted that segments of glass can enlarge the characters of writing, rendering them legible even for people with weak sight. Although Bacon never traveled to Italy, to test his theory, he sent to Rome some magnifying lenses for reading to French-born Pope Clement IV (r. 1265-1268).

Perhaps because of this, Bacon is often considered the inventor of eyeglass lenses. However, another contender is the Florentine naturalist and physicist Salvino D’Armati whose tombstone reads: “Here lies Salvino D’Armati of Florence, inventor of spectacles. May God pardon his sins, 1317 AD.” D’Armati had impaired his vision performing light-refraction experiments and sought a personal remedy. In 1280 he and Alessandro da Spina, a Dominican monk at the Convent of St. Catherine in Pisa, found a way to enlarge objects by using two pieces of glass having a specific thickness and curve. A few years later da Spina supposedly invented eyeglass frames, although many scholars insist that eyeglasses originated in China and were brought back to Venice by Marco Polo.

Although we’ll never know for certain because he neglected to identify himself, another monk from Pisa named Giordano, who coined the word occhiali, may have been referring to da Spina, when he declared in a sermon he gave in 1306 at the church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence: “It’s not yet 20 years since the art of making spectacles, one of the most useful arts on earth, was discovered. I, myself have seen and conversed with the man who made them first.”

The earliest surviving documents about making eyeglass lenses were written in Venice in 1284, thus earlier than Giordano’s remarks, but they confirm the chronology. These regulations for the crystal workers guild state that lapides ad legendum, or magnifying glasses, must be made of rock crystal, not inexpensive glass. Another document dated June 15, 1301 mentions vitreos ab oculis ad legendum, or reading glasses, for the first time.

Even if their earliest documents are Venetian, Florence was definitely the first city to mass-produce eyeglasses. Documents reveal that between 1413 and 1562 there were 52 spectacle makers there and list the locations of their shops. Thus, even if we can’t put a face on the inventor, the first European eyeglass craftsmen lived in Tuscany and Venice, and, at least in Europe, eyeglasses were first used in Italy.

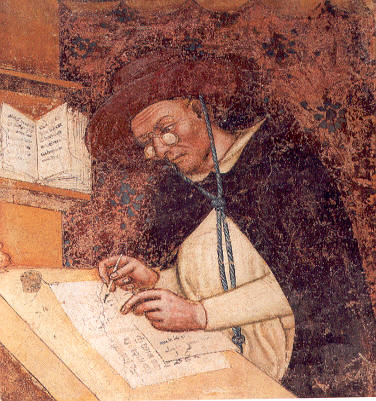

Like many medieval inventions, eyeglasses were first greeted with suspicion. Dominican friars played a decisive role in their dissemination because so vital to their daily needs as scribes. The Franciscan Order, already widespread throughout Europe, also made spectacles and disseminated the art outside Italy. The earliest record of spectacle-making outside Italy is a Nuremberg town council decree passed in 1478.

Naturally, thanks to Gutenberg and his invention of the printing press, the translation and circulation of the Bible and of works by ancient Greek and Roman writers, and the foundation of numerous universities, the literacy rates rose steadily throughout Europe and greatly stimulated the demand for spectacles, although it remained the privilege of a few: mostly clerics and scholars.

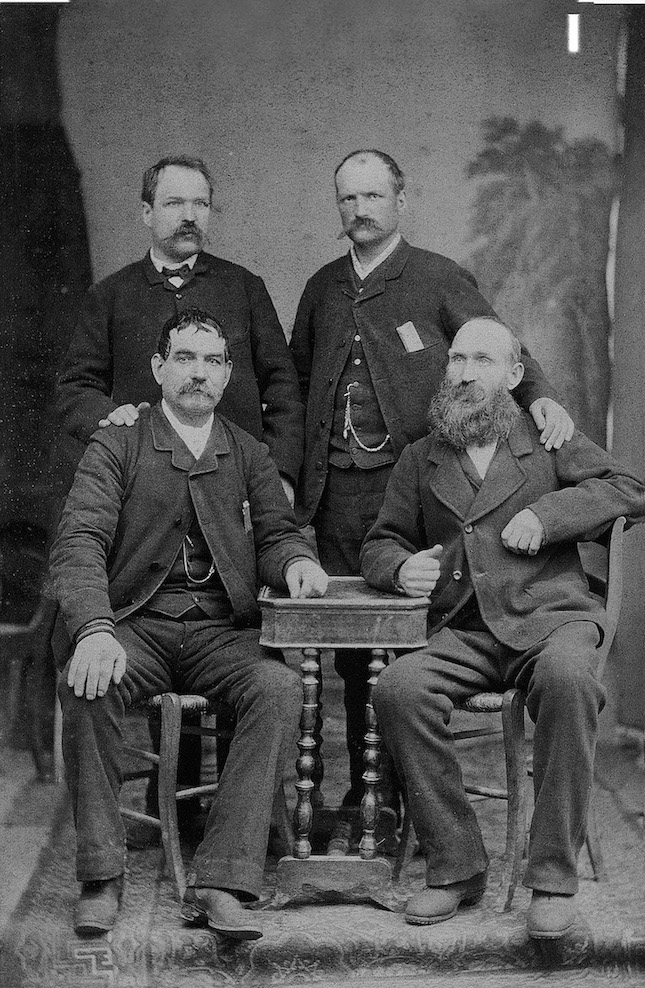

In Italy artisans continued to make eyeglasses until Angelo and Leone Frescura and their partner, Giovanni Lozza opened their first factory in 1878 in Calalzo di Cadore, a remote mountain town in the Veneto not far from Belluno. Still one of Italy’s most important industries, more than 80 percent of the eyeglasses manufactured in Italy continue to be made nearby, also meeting 69% of the European market.

To learn more about Italy’s historical connection to eyeglasses and other vision correctors, visit the Fondazione Museo dell’Occhiale Onlus with its 4,000 artifacts, Via Arsenale, 15, 32044 Pieve di Cadore, tel. 0435-500213.

Next door to the birthplace/now museum of the Renaissance painter Titian, you will find all types of eyewear on display on the first floor; on the second, a library and photographs, machinery and utensils illustrate their local manufacture.