On until May 28 at Rome’s Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea is the whimsical, quirky, and unique exhibition: Food Age: Food as Influencer, curated by the German photographer Inga Knölke and Spanish-born designer Martí Guixé, who divides his time between Berlin and Barcelona.

Food is essential for our survival, necessary for our daily life. We cannot live without eating. Recently food has also become more “in”, the center of our attention, than high-fashion and travel, on the tip of everyone’s tongue even without reaching anyone’s digestive system: daily TV interviews with chefs, food magazines full of recipes, blogs, juxtaposed with stories warning of climate change, droughts, famines, food waste, and politic supply interference, the most recent being the Russian blockage of Ukrainian ships carrying grain to nations in Africa risking starvation.

In Food Age: Food as Influencer Knölke and Guixé have changed the emphasis of food’s edibility and its nutrition to its artistic and reflective importance, a ubiquitous influencer, that can actively reshape the present and hint at numerous still unpublicized design projects and experiments for the future.

On display are some 100 artworks; four: Pie Poster, SPAM, Scaled model of a crisp, and Food Design Models 1997-2015 are by Guixé, who interprets food design as a way to re-evaluate and re-design the structure around food, the industry and the consumer. He sees food as an edible designed product, an object that negates any reference to cooking, tradition, and gastronomy. “I am only interested in food,” he says, “as I consider it a mass consumption product and I like the fact that it is a product that disappears—by ingestion-and is transformed into energy. Most of my food design projects are not commercial, but are a way of defining a new perception of this kind of product. They follow a clear conceptual line: they have nothing to do with cuisine.”

Elsewhere Guixé’s works have been exhibited at MOMA, MACBA in Barcelona, Triennale in Milan, MART in Rovereto, Centre Pompidou, and Mudac in Lausanne. The only work, a photograph, on display here by a famous multi-starred chef, Ferran Adrìa, owner of the now-closed El Bulli, voted the world’s best restaurant 2006-2009, is Capuchino de habitas a la menta Menù El Bulli (2003) owned and on loan here by Guixé.

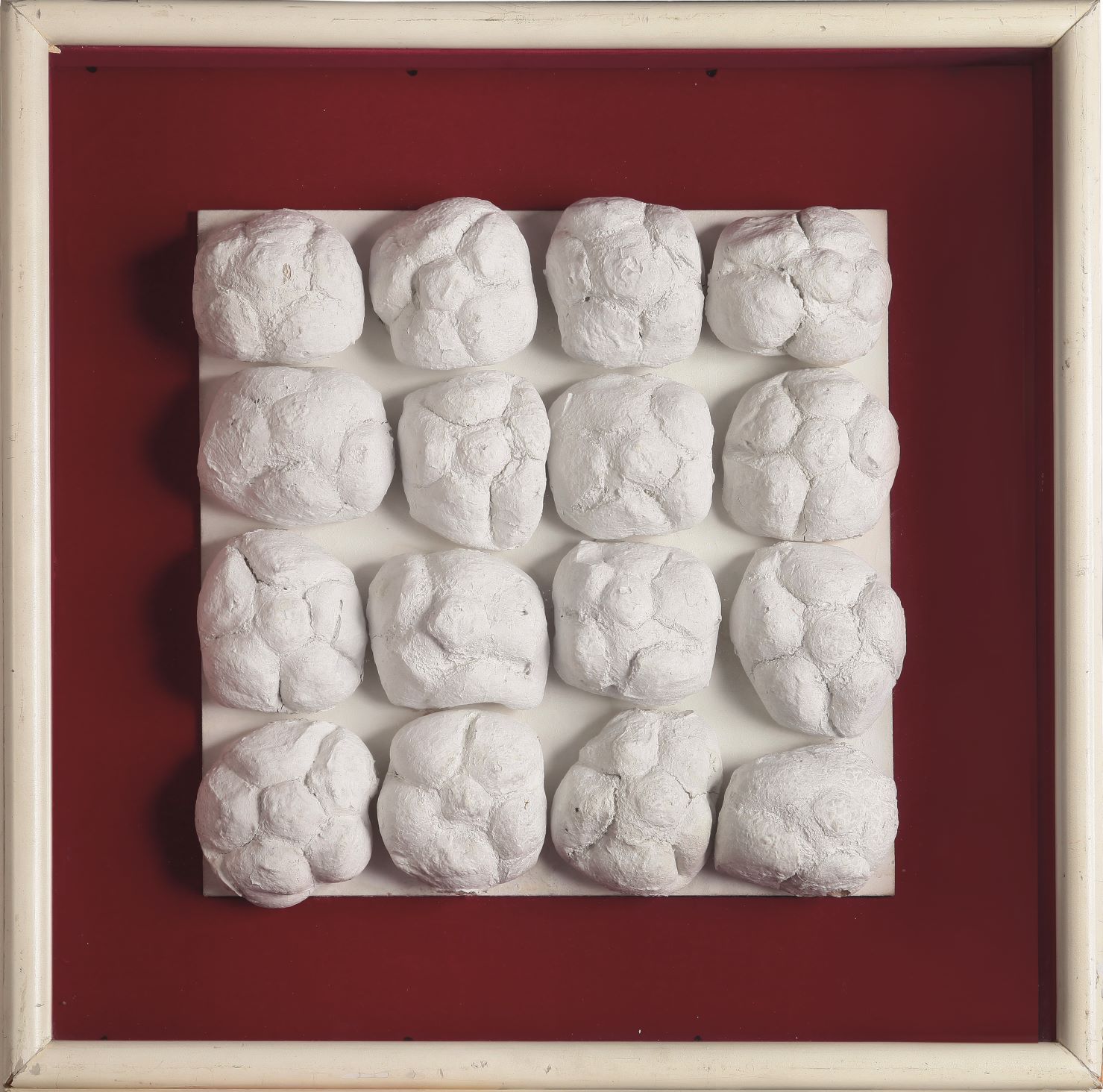

Food Age: Food as Influencer presents a wide range of re-elaborations of the theme, representative of the many ways in which artists look at food. In the exhibition there are works directly linked to food: drawings, prints, products or artifacts made with edible materials, such as Paul McCarthy’s Chocolate Nose Bar (2000) or multi-media works by Antoni Miralda (1973) made with bread, pasta and rice. By changing the color of these ingredients, he transfers them from their daily use to the world of art. Another example is Piero Manzoni’s alteration–also of bread: 16 rosette or hard-crusted Roman rolls. By painting them with white he solidifies them into a sculpture entitled Achrome (1962). Similar is Antje Dorn’s Quality Street Box (1996), where models of food bars, formally unfinished, construct non-textual phrases.

Abstract works, the press release tells us, are “Raquel Quevedo’s polymeric and dystopian aggregates (2022-3) which show an original way of manipulating matter to create a hybrid and somewhat unprecedented process, close and distant at the same time from the culinary method, while new technologies lie at the basis of the works (2023) by the Swedish duo Wang & Söderström, who investigate the space of intersection between living matter and nature.” Johanna Schmeer’s Bioplastic Fantastic series (2014) was created with the intent of raising questions about the future of food and the applications of biotechnology and nanotechnology that could become part of our daily lives. On display are her objects made of enzyme-enhanced bioplastics, halfway between objects and living organisms.

Less abstract and more practical is a large didactic poster by the Japanese botanist, philosopher and author of The One Straw Revolution (1999) about so-called natural or non-intervention agriculture, a return to the authentic relationship between soil and food production. Also on display is his Seedballs (also 1999) more specifically hands-on about this natural method of farming that requires no machines, no chemicals, and very little weeding.

Probably the most eye-catching artworks here are Rubén Verdú’s Heliospora (2022), a lollipop made of gold, diamonds, and sugar meant to encapsulate all the energy of the sun, Serbian-born, naturalized American Marina Abramovic’s 10-minute multi-media video The Onion (1995), of an elegant woman munching a raw onion complete with skin, and Agnieszka Polska’s photograph, A Glass of Petrol (2015).

Also on display are a conspicuous selection of late-19th-century/early 20th-century still lifes of food by Italian artists such as Casorati, Cassinari, De Pisis, Gentilini, Maffai, Morandi, Pascali and Vedova, to name but a few, all from the Galleria’s permanent collection.