At Rome’s Museum of Etruscan Archeology, Villa Giulia, I saw an intriguing documentary by Dario Prosperini, a video-journalist for Corriere della Sera and cineaste. L’anello di Grace tells the story of a unique archeological find, the 6th-century BC tomb of an Etruscan high-ranking official containing the skeletons of a man and wife, bronze and terracotta pots, two drinking cups, perhaps a gold ring, and a ceremonial “chariot”.

The story, which still has no ending, begins on February 8, 1902, when a farmer from near Monteleone di Spoleto in Umbria, Isodoro Vannozzi and his son Giuseppe unearthed the tomb. On March 28, 1902 instead of reporting their finds to the authorities, the Vannozzi sold the chariot to Benedetto Pietrangeli, an antique dealer in Norcia for 900 lire.

On May 14, 1902 Carlo Fiorilli, an official of the Ministry of Education, sent a telegram to the Prefect of Florence asking him to locate the chariot because it had disappeared from Norcia. Two days later, when questioned by the carabinieri, Pietrangeli admitted he’d bought it and then sold it in Rome without asking permission, but didn’t know to whom. The “unknown” buyer Cavaliere Ortensio Vitalini was the King of Italy’s numismatist, and therefore, untouchable, even if a month later the Italian Parliament passed a law making it a crime not to report finding archeological artifacts, and worse still, to export works of art abroad.

No action was taken against Vitalini even after Count Giuseppe Tornielli, Italy’s ambassador to Paris, wrote author-of-the-law Minister of Education Nunzio Nasi that the chariot the Government was looking for was in Paris. Tornielli added that a certain Pitt & Scott Company (we now know was Vitalini’s fictitious intermediary) offered to sell it to him for 300,000 francs.

The next we know, is that the chariot arrived in New York on February 16, 1903; that it was amply publicized in New York Tribune’s illustrated supplement on October 26, 1903, and that the Metropolitan Museum of Art first put it on display on November 28, 1903.

We also know that Archeologist/Senator Felice Barnabei, also the first Director of Villa Giulia, immediately attacked the Government for not preventing the theft of Italian art. He was the only politician to do so for over 100 years—that is until 2004 when the Municipality of Monteleone consulted a lawyer from Atlanta, Georgia, but with Monteleone origins, Tito Mazzetta, for advice about extraditing the chariot. The Met refused to budge, rebutting that the thirty-year limit for returning works-of-art was long over and that Italy had no document proving that the chariot hadn’t been bought legally.

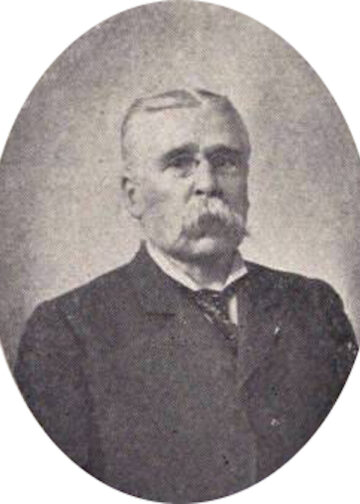

In 2018 the story about-faced. Guglielmo Berattino, a historian from Ivrea, on a vacation in New York, went to the Metropolitan, where he saw the chariot. He was pleasantly surprised to discover that it had been bought by Luigi Palma di Cesnola, who had been born in 1832 in Rivarolo Canavese near his hometown of Ivrea. Berattino had grown up knowing of Cesnola who was a local hero, especially after he moved to New York in 1858, thanks to his brilliant career first as a soldier in the Civil War, then as the US consul in Cyprus (1865-77) and lastly as the first Director of the Met (1879-1904).

Home again, Berattino decided to research Cesnola in Ivrea’s Municipal Library. There the director gave him a recently purchased binder filled with papers concerning a Count Gioachino Toesca Caldora di Castellazzo, a childhood friend of Cesnola. Among its hundreds of letters Berattino found 16 signed international bombshells: accounts of how the chariot had been stolen including the sum of 250,000 lire paid for it by the Met via a wire transfer to Vitalini. The letters, dating from 1902 before the sale and during the sale’s negotiations until 1904, are between Vitalini and Cesnola; between Toesca, the intermediary, and Vitalini; between Vitalini and Luigi Roversi, Cesnola’s assistant at the Met, and between Cesnola and Toesca.

In one of the last two letters Vitalini orders Cesnola and Toesca not to tell anyone how the chariot had reached the Met. Vitalini writes that in Italy the Government is investigating the matter so that, if any journalist, Italian or American, asks about the chariot, the two must remain silent. In the second letter Cesnola writes to Toesca saying, how dare Vitalini tell him what to say and not say? This is clearly damning evidence of a theft “Made in Italy” with Italian accomplices on USA soil.

In the latest development, on November 9th the Ministry of Culture requested a copy of the documentary that relates the entire story of the chariot, “L’anello di Grace”, which Prosperini gladly donated free-of-charge on December 2nd, and that certainly provides the Italian Government with the necessary proof for the return of the chariot.

With the British Museum negotiating with the Greek Government about returning the Elgin Marbles at least partially or temporarily, it now remains to be seen if the Met will follow suit and return what is undoubtedly Italian cultural property.