The Monument Men was a group of 348 men and women from 14 nations in the Allied Forces who worked in the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives (MFAA) section of Civil Affairs during World War II to recover and restitute cultural treasures looted by the Nazis. The major part of their work was post-War.

Italy had its own similar version of Monument Men. Art historians, archeologists, librarians, museum directors, and superintendents and officials of the Fine Arts Administration, but not soldiers, they worked clandestinely after the signing of the Rome-Berlin axis (1936), first-of-all before and during combat, to protect Italy’s monuments from war damage, to hide Italian art treasures from the Nazis seeking to steal them for Germany, then keep them hidden from German looters and from bombs after the 1943 armistice, and finally to retrieve the works-of-art taken to Austria for Hitler’s Führermuseum in Linz and Göring’s private collection at Carinhall, his hunting lodge near Berlin.

The temporary exhibition Arte Liberata 1937-47, masterpieces saved from the war, on at the Scuderie in Rome until April 10th, tells this little-known Italian story for the first time. On display are some 100 works-of-art out of the some 12,000 rescued and returned home, mostly paintings but some sculptures, ceramics, tapestries, and manuscripts (including Rossini’s correspondence and scores) on loan here from some 40 churches, museums and libraries in Ancona, Ascoli Piceno, Bologna, Cassino, Civita Castellana, Fabriano, Florence, Gaeta, Jesi, Lucca, Milan, Naples, Palermo, Pesaro, Rome, Turin, Urbino, Venice and Viterbo, and never before exhibited together. Also on display are photographs, inventories, correspondence, diaries, photographs, films, and maps of the hiding-places.

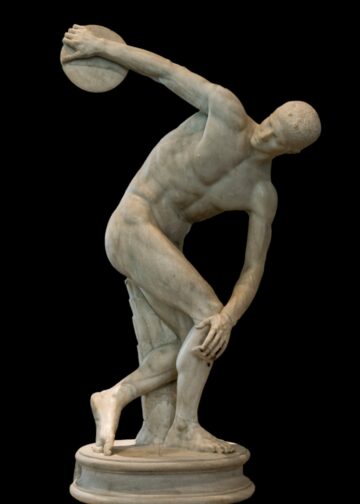

After the Rome-Berlin Axis Hitler was confident that he could display the Discobolus Lancellotti, a first-century A.D. Roman marble copy of Myron’s original bronze as the centerpiece of the 1936 Berlin Olympics but a 1909 law clearly stated that the statue he coveted couldn’t leave Italy. Nonetheless, in 1937, thanks to the intercession of Prince Philip of Hesse, the cultured husband of Mafalda, Italy’s King Vittorio Emanuele III’s second daughter who died at Buchenwald in 1943, Galeazzo Ciano, Mussolini’s son-in-law and Italy’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, agreed to “sell”-a new but pathetic Nazi tactic-the statue to Hitler for a pittance-5 million lire. The first of Arte Liberata’s three sections, Forced Exports and the Art Market, opens with this statue.

Also on display here are photographs of models for the self-aggrandizement Führermuseum (which was never built), a first-century A.D bronze statue of a baby deer from the Villa of Papyri at Herculaneum that Göring confiscated and put in his garden at Carinhall displayed here in front of an enlarged photograph of him with Hitler admiring the statue. Nearby is Göring’s ledger with his meticulously handwritten numbered list of the many Italian artworks Hitler planned to “buy” for Germany. The purchase of the Discobolus was the writing on the wall for Giuseppe Bottai, Italy’s minister of Education and Italy’s intellectuals and museum directors.

Section 2, “Displacements and Rescues”, includes many photographs, which document monuments and museums being covered in scaffolding, sand-bagged and fire-protected and artworks being crated and then being driven at night, with no lights in private cars and trucks at great personal risk and no funds for fuel, to hiding places. The protagonist of this tour de force was Pasquale Rotondi, the young superintendent of the Marche, who in June 1940 set up a national depositary for some 6,000 masterpieces from Urbino, Venice, Milan and Rome in the cellars of the Palazzo Ducale in Urbino, and by 1943 for another 6,000 in Sassocorvaro and Carpegna.

The third section, “The End of the Conflict and Restitutions“, is divided into two sections. The first tells the story city by city of Rotondi’s courageous colleagues and how, after there was no more room in the Marche’s depositories, thanks to Rotondi and art historian Giulio Carlo Argan–later mayor of Rome (1976-9)– and to Giovanni Montini, Pope Pius XII’s Secretary of State, later Archbishop of Milan and still later Pope Paul VI (1963-78), the artworks were hidden in Vatican City and the Benedictine Abbey of Montecassino. Ironically, when the Abbey became the frontline, the Nazi troops stationed there persuaded Abbot Gregorio Diamare to let them drive the Abbey’s treasures and the hidden artworks to safety in the Vatican.

The second part concerns the Italian officials’ collaboration with the Monument Men in particular for the recovery and return to Italy of some 6,000 artworks stolen by the Nazis. A panel explains that 98% of the artworks in the Italian inventories, those hidden in Italy and the Vatican and those taken to Germany, have been returned. Among the most famous displayed in Arte Liberata are: Titian’s Danae, which Göring hung in his bedroom, Guercino’s Santa Palazia, Hayez’s portrait of Manzoni and Holbein’s of Henry VIII, Signorelli’s Crucifixion, Piero della Francesca’s Madonna of Senigallia, which Rotondi hid under his bed with Giorgione’s Tempest. Only the Italian Jewish artifacts and the contents of Rome’s Jewish Library were never found. The last artifact, Matteo Civitali’s 15th-century terracotta Bust of Christ from Lucca, discovered for sale in an auction catalog and worth over 1 million euros, returned from Germany in December 2017.

I had a personal reason for wanting to see Arte Liberata. My great-grandmother Florence Bernheimer Walter was a cousin of Otto Bernheimer, the owner of Bernheimer-Haus, a world-famous antique store at Lenbachplatz 3 in central Munich. Göring was a client. During the Nazi dictatorship, the business was initially protected because Otto was the Honorary Consul of Mexico. However, in 1938 when he refused to relinquish the store and its contents, Göring sent him and his two sons to Dachau until they agreed to exchange it for a coffee plantation in Venezuela and take with them Göring’s aunt and her husband, who

was Jewish. Göring was condemned to death at Nuremburg but killed himself by swallowing a smuggled cyanide pill on November 15, 1946, hours before his execution. That same year Otto had returned to Munich and received Bernheimer-Haus again as Wiedergutmachung (reparations).