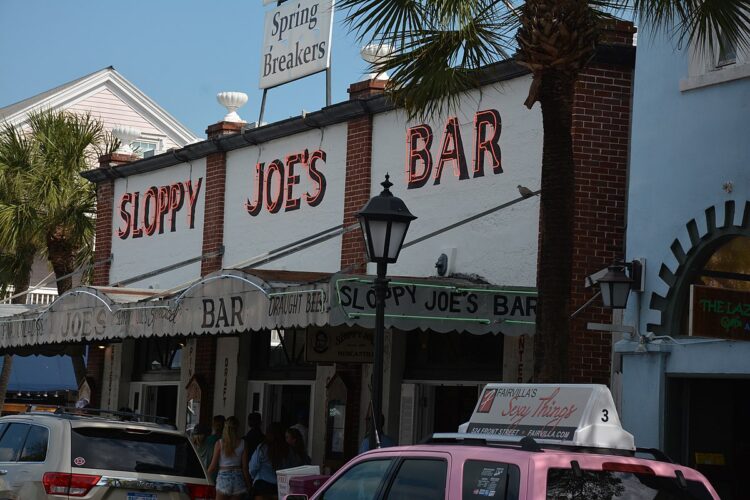

Hemingway scholars and fans are salivating at the prospect of scrutinizing, or simply enjoying, a “new” Hemingway novel or short story—more than 60 years after his death by suicide. In 1939, after his second marriage, to Pauline Pfeiffer, crumbled, Ernest Hemingway, who was known to hang on to everything he ever wrote, left his belongings in the storeroom of Sloppy Joe’s Bar, his favorite hangout in Key West, Fla. He never returned to collect them and there they stayed until 1961.

After Hemingway’s death, his fourth wife, Mary Welsh Hemingway, went through the material, packed up what she wanted, and gave the rest to longtime friends, Betty and Telly Otto Bruce, known to his friends as Toby. Toby Bruce was part of Hemingway’s inner circle for years, not only as his right-hand man, but also as his contractor, mechanic and sometime chauffeur.

The trove of materials spent decades uncatalogued in cardboard boxes and storage containers, surviving hurricanes and floods—basically, forgotten by the Bruces and by Mary and unknown to the public.

Then, years ago, Betty and Toby’s son, Benjamin Bruce (known as Dink) and a local historian, Brewster Chamberlin, began creating an inventory of the haul in consultation with the Hemingway scholar Sandra Spanier. It was here, amid bullfighting tickets, checks, newspaper clippings and letters from his lawyer, family members and friends like the writer John Dos Passos and artists Joan Miró and Waldo Peirce, that they discovered a stained brown notebook. Inside was Hemingway’s first known short story, about a fictional trip to Ireland, written when he was 10 years old.

The items, part of the most significant cache of Hemingway materials uncovered in 60 years, are in a new archive recently opened to scholars and the public at Penn State University. The stash includes four unpublished short stories, drafts of manuscripts, hundreds of photographs, bundles of correspondence and boxes of personal effects that experts say are bound to reshape public and scholarly perception of an artist whose life and work defined an era.

Carl Eby, the president of the Ernest Hemingway Foundation and Society, said he was “truly floored” by the bounty of material from an artist best known for the taut, understated writing of works like “The Sun Also Rises” and “The Old Man and the Sea,” dispatches from World War II and the Spanish Civil War and his larger-than-life persona as a hard-drinking, hard-working outdoorsman. An image that took “Papa Hemingway” a lifetime to create and that then devoured its creator who could no longer live up to what had always been mere mythomaniacal hyperbole.

“Hemingway reinvented modern American prose and the short story. His best work is deeply moving and rich in meaning and psychological complexity,” Eby, who is a professor of English at Appalachian State University, said. “He seemed to live on an epic scale, in fascinating times, in fascinating places, and because he was mythologized during his own lifetime, his public image to this day — for better or worse — retains all the allure and power of the mythic. There’s enough new material here to generate new biographical and interpretive insights for years to come.” It remains to be seen what new facets of the man and the writer will emerge from this new material and fans and critics are waiting with bated breath.