This June 16th will be the 100th anniversary of the publication of James Joyce’s infamous novel, “Ulysses”. The book was first serialized in parts in the American journal The Little Review from March 1918 to December 1920 and then published in its entirety in Paris by Sylvia Beach on February 2, 1922. James Joyce is a writer who is known for being difficult. The average reader who picks up one of his books will read a couple of pages and put it down, scratching his head in confusion. Starting with the relatively “easy” Dubliners (1914) and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916), he went on to write Ulysses (1922), a reputedly impenetrable book that retells the story of the Odyssey as the new Ulysses, Leopold Bloom, makes his way around Dublin on one famous day, June 16.

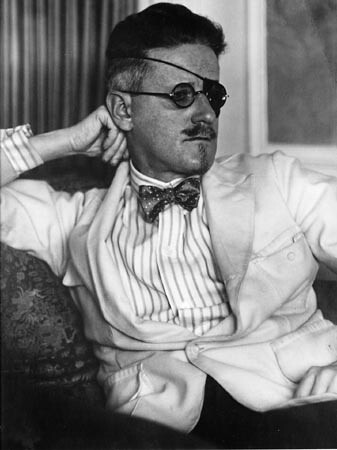

Every college professor teaching the weighty works of James Joyce–iconic Dubliner and narcissist–loves to repeat the story that Joyce proudly claimed having put in enough puzzles and conundrums in his Ulysses to keep one hundred professors busy for one hundred years.

Most likely the story is apocryphal, he probably never actually said those words, but every student who has agonized through Joyce’s literature thoroughly believes it. And knowing how Joyce suffered from a bad case of ‘the arrogance of genius’, he may not have said the actual words, but the sentiment was genuine. He really did pride himself on writing for the intellectual, on being the master of obscurity. If you want to get to the bottom of the Joycean well of literary genius you’ll need patience and commitment.

By the time that he had gotten to writing Finnegan’s Wake, (1939) he had not only abandoned almost all usage of punctuation, but created his own language, an amalgam of all the Romance languages, plus more. Here is one representative line: “What clashes here of wills gen wonts, oystrygods gaggin fishy-gods!”

James Joyce’s literature is a cult for many, and a love-hate relationship for some. Mostly, it’s a question of hate for the students who–like me decades ago–at first study the text as unequipped undergraduates, and frustration for all those–again like me at a later date–who have to teach it to the next batch of unequipped students. But equally, for millions worldwide, and most of Dublin’s population, the pain is worth the reward: he is a god. But let’s get back to “Ulysses” and June 16, “Bloomsday”.

On that day, thousands revel; they read Ulysses aloud, celebrate it in drama and song, “and above all, get drunk” (Scott Huler in “No-Man’s Land”). It’s been compared to a science fiction convention that is spread out all over Dublin, where people walk around all day with their noses in the book, following Leopold Bloom’s itinerary street by street, door by door. This is where reality and fiction rub up against each other with no discernable boundaries. For some, the book is an obsession–even a cult– for others, pretentious, and for many others, unreadable.

Yet Dublin (and to a lesser extent Trieste, where Joyce lived for 15 years) is the mecca of the Joycean cult: thousands gather to enact scenes from the book, engage in panel discussions about the book’s opacities and retrace the steps through the Dublin of Leopold Bloom’s day.

I would venture to guess that the thousands who celebrate Bloomsday don’t know and don’t care about the intricacies and merits of the literary work, but know plenty about the book’s celebration of life. Sensuality, sex, passion, joy, these are the traits that caused the book to be banned as obscene in the UK and the US when it came out in 1922.

Molly Bloom incarnates these universal and eternal passions in Ulysses, and they never go out of fashion; for these have nothing to do with ideas, rationality and the intellect. They are embedded in our DNA—they are the very stuff of life. Without them there would be no you or me because humanity would have never survived through the millennia. Like Thornton Mellon, the character played by Rodney Dangerfield in the hilarious movie, “Back to School”, who is blown away by the super-erotic recitation by the sexy professor of Molly’s famous monologue, let’s celebrate James Joyce’s Ulysses and embrace Molly Bloom’s passion for love, sex and the positive forces of life; and like her, say “yes I said yes I will Yes” (original punctuation).