From antiquity to the Middle Ages, humans had a conflicting relationship with nature, seeing it as representing either divine or satanic forces. In the vanguard of a change in perspective toward the natural world was St. Francis of Assisi (ca. 1181–1226) who is now, thanks to his pioneering work, a patron of ecology and Earth Day. He set forth the revolutionary philosophy that the Earth and all living creatures should be respected as creations of the Almighty.

St. Francis’ affinity for the environment influenced the artist Giotto (ca. 1270–1337), who revolutionized art history by painting figures which were three dimensional and including natural elements in his religious works. By taking sacred images away from Heaven and placing them in an earthly landscape, he separated them definitively from their abstract, unapproachable representation in Byzantine art.

Giotto’s works are distinctive because they portray daily life as blessed, thus demonstrating that the difference between the sacred and profane is minimal. Disseminating the new ideas of St. Francis visually was very effective, as the general populace was illiterate. Seeing frescoes reflecting their everyday lives in landscapes that were familiar changed their way of thinking. The trees, plants, animals and rocky landscapes were suddenly perceived as gifts from the Creator to be used, enjoyed and respected. Furthermore, Giotto recognized that the variety of dramatic landscapes would provide spectacular visual interest in the works.

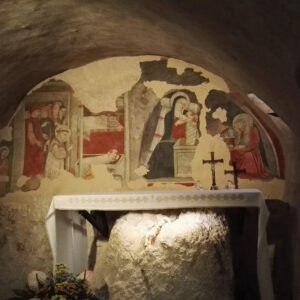

Francis staged the first living Nativity scene or presepe on Christmas in 1223 in a limestone grotto at his monastery at Greccio. Interestingly, Francis had to obtain papal permission to use an ox and an ass in the manger scene to avoid the charge of novelty. Once approved, he invited the local townspeople, along with their animals, to participate in a recreation of the holy event. He situated the participants, including livestock, in the grotto and then placed a newborn in a manger cushioned with hay. After, Francis stepped forward and lead a celebratory mass. The altar was a block of limestone, still visible today. This brought the message of Jesus’ birth down to Earth so that the lowliest person could identify with the humble manner in which He was born.

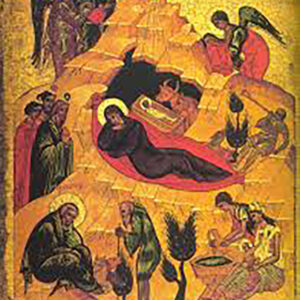

If we look at a Byzantine representation of the Nativity (first part of the 14th c.) we can see Jesus’ birth depicted in a cavern in a landscape complete with rocks, mountains and trees. The Byzantine style, lacking perspective and scale, portrayed the figures and landscape elements one-dimensionally, configured in a single plane. In religious art, this effectively created a psychological distance between the sacred events and the viewer, evoking a reverential experience.

Giotto revolutionized art by taking Byzantine iconography and humanizing it. Following Francis’ lead, the Nativity thus became a natural event.

Using elementary perspective techniques, he was able to compose a sacred scene that appeared similar to a person’s daily life.

In this way, the viewer had a direct experience with the miraculous, allowing him to internalize the supernatural event and ultimately transfigure his human consciousness into a vessel for the divine.

In “St. Francis receiving the stigmata” (1318) Giotto uses a rock, which has been sliced open, to imitate the wounds in St. Francis’ hands and feet. The Franciscans used this location, the monastery at La Verna, and this divine occurrence, to demonstrate that mountains were vital in the sacred ritual, thus promulgating the idea that they would provide a nearness to God and a source of divine inspiration. In fact, today thousands of pilgrims arrive at the monastery, built on a mountainside, to visit and pray at the sacred grotto.

In “St. Francis gives his mantle to a poor man”, Francis demonstrates his commitment to refuting worldly goods by giving his mantle to a poor man. He has abandoned his fine clothing and is now dressed in the simple sackcloth emblematic of the congregation of friars. It is said that Francis walked from one village to another, where he would preach. Giotto places him on a solitary path out of town. In this way, out of sight of anyone, he practiced his charity—anonymously and in the midst of nature. A scene like this would resonate with any viewer as they would understand the landscape and could recognize the local cities with their houses, churches and towers.

They could see familiar mountain paths and remember their own difficult journeys, be them psychological, spiritual or corporeal. And so, through Francis’ example, and ultimately through their own actions, seen or unseen, they could become saints as well.

The frescoes, altar panels and paintings reflecting the new naturalistic style also provided visual accompaniment to the popular preaching approach practiced by St. Francis– not in Latin, but in the spoken language (Umbrian form of Italian). Together, the visual and the audible messages centered on the mystery of the Incarnation and on the need for repentance. But oral discourses were ephemeral and the written word was accessible only to the elite. Therefore, Giotto’s technique of integrating sacred images into the Earthly landscape was the most powerful form of proselytization as illiteracy was widespread.

And so, St. Francis and Giotto, who never knew each other, were linked by history and art. Unbeknownst to them, their legacy would ultimately change Western piety, art and natural history. Much of today’s ecological movement has embraced the tenets espoused by St. Francis. Giotto not only immortalized Francis’ idea of the sacredness of nature by carefully placing and configuring natural elements realistically in his frescoes, he provided the visual record which, after 800 years, is with us today.