The director Alex Proyas reminds us in the movie “The Crow”–that was curiously fatal for the young Brandon Lee—that, “Childhood’s over the moment you know you’re gonna die”. Since the very beginning of the development of consciousness, every human being starts to face the problem of death. The urgency of finding an answer to what is clearly the biggest question in everybody’s life becomes stronger the closer we feel to be to the inevitable epilogue. Under particular historical circumstances death becomes such a common companion that we are able to free our vision from fear and start considering it from a different point of view. This particular level of super-consciousness has often been the center of philosophical and artistic researches producing a vast array of documents and images.

The “Danse Macabre” or Dance of Death, in particular, is a pictorial allegory born around the 15th Century of the concept of death. This kind of image is typically associated with similar symbolism common during the Middle Ages such as the legend of the “Three Living and the Three Deaths” and the most common “Triumph of Death”. They are often represented together as is the case with the fresco in the Oratorio Dei Principi in Clusone, Italy, attributed to Giacomo Borlone (1485).

This notable example of coexistence of the three major representations of death is particularly interesting in relation to their significance. This fresco is an ideal representation of the transition from a spiritual and Catholic idea of death to a more secular and pragmatic vision. During the Middle Ages, death starts to be represented as a state of physical decadence (Three Living and Three Deaths), then as an unstoppable destroying power (Triumph of Death) and, finally, as the ultimate social leveler (Danse Macabre).

The latter can be considered as the evolution of the classical definition of “Memento Mori”, from which it inherits the formal idea of the acceptance of death, developing a cynical and almost humoristic approach. All the drama of the Grim Reaper spreading fear and suffering with its sickle suddenly disappears just to become a paradoxical dance. Screaming figures leaving the floor to lute-playing skeletons while terrorized faces are replaced by almost bored expressions. The affliction typically associated with death is surpassed and the subsequent stage of acceptance emerges in the form of sarcasm.

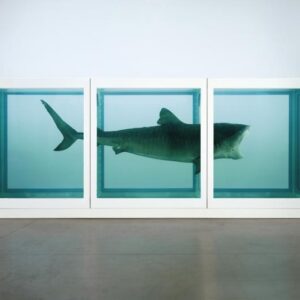

Interestingly this is the same attitude we find in contemporary artworks like the seminal “The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living” by Damien Hirst (1991). The entire bouquet of reactions inspired by the sculpture, ranging from fear to fascination, overlooks the fact that the subject is actually a dead animal. The subconscious fear generated by the idea of a living shark is strong enough to obliterate the simple truth that the animal is dead and, presumably, unable to harm the viewer.

The radical change in the popular idea of death, represented by the Danse Macabre, corresponds to the end of the great Plague that decimated the European population in the 14th century. What was left from one of the worst pandemics in the history of humankind was the notion of the substantial democratic nature of death. Such a statement, apparently obvious to the modern man, was almost anarchic in the context of a pre-Reformation society.

The simple idea that death could subvert every human hierarchy, temporal and religious, was the real turning point behind the Dance of Death. The living figures depicted in these allegories are not only dancing with the death but they’re most notably dancing together. Nobles and cardinals share the floor with peasants and wounded and they all dance to the same death symphonies. The relevance of this statement for medieval society is the equivalent of the abolition of forced perspective in ancient Egyptian art.

The Plague made the vision of death so common that even a strong imaginary like the one developed in the “Triumph of Death” was unable to create any reaction. The almost morbid vision behind such an allegory was only able to recall sad memories instead of existential fear and this corroded its evocative power.

Painters like James Ensor, who embodied the Flemish imaginary with his 19th century Bohème, would have later shared such a vision. In his paintings, monsters and skeletons join uninterested crowds in what appears to be a post-apocalyptic party.

No one cares about the peculiar nature of these guests and the play of life simply goes on without paying any particular attention to feral context.

Under certain circumstances, like a global war or a plague, death becomes so common as to be almost generally accepted, as it happened with the idea of the nuclear apocalypse during the Cold War. Right after the 14th century, the primordial fear connected to the unpredictability of death was over and this made it possible to start a new investigation on the social implication of the “final” event. This is when death stopped being considered only as a menace and suddenly became the opportunity to equalize a society based on social differences. Suddenly what was considered to be the tragic epilogue started to get a positive acceptance from a social, and not just a religious, point of view.

Death is fair and its appearance cancels every injustice. This leads to a vision that considered the impact of death on a human being proportional to the inequality he suffered (or benefited from) during life. The higher you’ve been flying in your life, the greater will be your fall to the ground after your death.

Such a scenario, predicted in the medieval Danse Macabre, founds its contemporary climax in the artistic research of Jake and Dinos Chapman. The feral images they create with their monumental sculptures are among the closest representations of the Dance of Death in modern days. The English duo applied the same concept of proportional justice to the symbols they identify as the pinnacle of evil for contemporary society: Nazism and Consumerism. In the series of works known as “Fucking Hell” (2008) they created 9 glass cases on the model of museum display cabinets showing a dystopian diorama of hell.

Merciless skeletons under the collapse of McDonald’s symbols torture thousands of Nazi soldiers in a macabre and paradoxical gore fest. The Chapman brothers actualized the mocking attitude of medieval dancing skeletons to an era of taboo destruction. What the viewers experience in front of this sculptures is the same sense of uncertainty and fascination that the medieval peasant had in front of a Danse Macabre fresco. The image is not just unexpectedly captivating, but it is even covered by a positive trait of supreme and ineluctable justice.

The estranging view of the Danse Macabre might have been conceived in the Middle Ages, but it maintained its strength over the centuries. The scenario we are living in, dominated by the first global sanitary crisis of the communication era, is totally unprecedented and will inevitably produce a great effect on artistic expressions, in particular those related to death. Art talks about life but artists need time in order to process the inputs they get form the world. For sure, the approach that our over-informed society developed towards the Covid-19 assumes a great significance in relation to the post-truth society. But the reality is that a few years will need to pass before we can get a full awareness of what will be left from the pandemic, and so art will need time before metabolizing the event. The evolution that the representation of death in art, and the Danse Macabre allegory in particular, will have after the Covid is still far away, but it is obvious that something will happen. After all, the imaginary that pushed Giacomo Borlone to paint his fresco is the same that lead Walt Disney to draw the Skeleton Dance in 1929, and is the same that will drive contemporary over this event. Like Ingmar Bergman’s film, “Seventh’s Seal”, the Danse Macabre is an ideal interaction between a man and his fate that will forever produce the most interesting of the effects. The end of fear and the nihilistic acceptance of the true and democratic essence of death: the end.