A mega-exhibition dedicated to Antonio Canova (1757-1822), generally considered the greatest Neoclassical sculptor of the late 18th and early 19th centuries is on in the Palazzo Braschi near Piazza Navona until March 15. There are 170 artifacts on display, many by Canova. The intent is of showing Canova’s deep attachment to Rome and the city’s ancient art, the inspiration for his sculpture.

They are on loan from the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, the Vatican Museums, the Gypsotheca and Museo Antonio Canova in Possagno, the Museo Civico in Bassano del Grappa, the Capitoline Museum in Rome, the Correr Museum in Venice, the Archeology Museum in Naples, the Accademie di Belle Arti in Bologna, Carrara and Ravenna, the Uffizi in Florence, the National Academy of St. Luke in Rome, the Musée des Augustins in Toulouse, the Museums of Strada Nuova-Palazzo Tusi in Genoa, and the Museo Civico in Asolo.

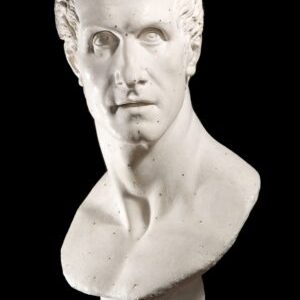

The exhibit, “Canova. Eterna Bellezza,” is divided into 13 sections: 1779: Canova to Rome; The Birth of a New Tragic Style; Canova and the Roman Republic 1798, when Napoleon imprisoned Pope Pius VI and took him to France, where he died a year later, and also when Canova left Rome for self-imposed exile in his birthplace to return two years later; during this period he dedicated himself more to painting because of a lack of marble for his sculptures; Hercules and Lichas; The Boxers; The Perfect Theorem: The Confrontation between Ancient and Modern; Canova and the Accademia of San Luca; Canova, the Inspector of Fine Arts; Canova and the Busts in the Pantheon; Canova’s Last Works for Rome; Canova’s Studio; “The Dancer” (Canova had a lifelong passion for dance. On display here is one of his three life-size sculptures of dancers. She has her hands on her hips and was created for Napoleon’s first wife, Josephine de Beauharnais; it arrived at the Hermitage in 1815. The other two are in the Museo Canova and in Berlin’s Skulpturensammlung.); and Canova’s Death and Glorification.

Canova was born in the Veneto in the small town of Possagno into a family of sculptors and stonecutters, including both his grandfather, Pasino Canova, and his father, Pietro. Nineteenth-century biographies of the artist suggest that Canova’s artistic talent revealed itself at an early age when, as a young child, he carved a lion made out of butter at a dinner party.

After five years of working in Venice, in 1779-80, 22-year-old Canova made a “grand tour” of Italy, during which he saw the great art collections of Bologna, Florence, Rome and Naples, as well as of Pompeii, Herculaneum and Paestum, experiences that he recorded in his travel diary. He noted, for example: “One must absorb ancient art into one’s circulatory system so that it becomes as natural as life itself”.

His aim was for ancient art to be born again in his contemporary sculptures and to model contemporary artworks through a filter of the ancient. “For this reason,” the press release says, “he can be considered the last of the ancient and the first of modern sculptors. He always refused to make copies of ancient sculpture, which he considered unworthy of a creator.” Therefore, he always refused to restore ancient sculptures, which he considered “intoccabili” (“untouchable”) so too perfect to copy. Some examples of the exhibition’s confrontation of the ancient vs. the modern are Canova’s Amorino (Cupid) on loan from the Hermitage vs. the Eros Farnese from the Archeology Museum in Naples and the Apollo Belvedere on loan from the Vatican Museums and the Louvre’s Borghese Gladiator vs. Canova’s Triumphant Perseus and his Creugante Gladiator, both from the Vatican Museums.

Besides the comparisons between ancient statues and Canova’s, the exhibition includes works by other artists, contemporaries of Canova’s also living in Rome, Gavin Hamilton’s paintings of The Legends of Paris from the Villa Borghese, portraits by Pompeo Batoni (his of Pope Pius VI on loan from the Vatican Museums opens the exhibition) and Jean-François-Pierre Peyron’s Belisarius Receiving Hospitality From a Peasant from Toulouse. Canova greatly admired this painting and called Peyron “il migliore di tutti” (“Best of All”).

In 1781 Canova opened his first studio in Rome, soon considered the center of modern as well as of ancient art, and he was proclaimed the new Phidias, the new Praxiteles. Therefore, his studio was a “must-see” stop for travelers on the official Grand Tour. His many VIP patrons throughout Europe included Popes Pius VI and VII as well as Napoleon and the Bonaparte family. To name a few commissions with Vatican connections: in 1783-1785 he arranged, composed, and designed a funerary monument dedicated to Clement XIV for the Church of Santi Apostoli, at the time acclaimed a new example of Classical perfection; in 1792 he completed another cenotaph, this time commemorating Clement XIII for St. Peter’s Basilica; in 1801 he sold to Pius VII his Triumphant Perseus, the first contemporary work-of-art to enter the Vatican Collections” and on display here in the section “The Perfect Theorem”: Ancient and Modern in Confrontation”.

The next year, in recognition of Canova’s stature, Pius VII designated him Inspector of the Fine Arts of the Papal States, a post formerly held by Raphael that gave Canova authority over the Vatican Museums and the export of works-of-art from Rome. Several years later, in 1815, after Napoleon was deposed, the same pope named Canova “Minister Plenipotentiary of the Pope” and sent him to Paris to recover the art that Napoleon had carried off to France. The mission was a success and in 1816, as a reward, according to Wikipedia, “Canova was appointed President of the prestigious Accademia di San Luca, inscribed into the “Golden Book of Roman Nobles” by the Pope’s own hands, and given the title Marquis of Ischia, alongside an annual pension of 3,000 crowns.”

On his own initiative Canova also started to sculpt his statue, Religion, its plaster-cast models from the Academy of St. Luke and the Vatican Museums are now on display, as are his clay models of his George Washington Monument and of his statue of Leopoldina Esterhazy Lichtenstein. The monument was a marble statue of George Washington portrayed as an ancient Roman general. Commissioned by the State of North Carolina in 1815, it was completed in 1820 and installed in the rotunda of the North Carolina State house on December 24, 1821. The building and the statue were destroyed by fire on June 21, 1831. The only work by Canova in the United States, it was replaced by a marble copy sculpted by Romano Vito in 1970.

Now at the height of his fame, in 1817 Canova designed his Stuart Memorial, its plaster-cast mold on display here, for St. Peter’s Basilica. It commemorates the last three members of the Royal House of Stuart: James Francis Edward Stuart, Pretender to the throne of England, his elder son Charles Edward Stuart, better-known as “Bonnie Prince Charlie” and his younger son Cardinal Henry Benedict Stuart, all three of whom died in exile in Rome. Ironically, King George III of England covered the expenses of this monument to his rivals.

In January 1818 Canova opened a new studio in Rome, at Via del Babuino 150/A-B, on the corner of Via del Babuino and Via dei Greci, in the neighborhood traditionally animated by artists’ workshops and home to many foreign visitors, thus potential clients. He intended to favor his most gifted student and certainly his only spiritual heir, Adamo Tadolini (1788-1863). Canova allowed Tadolini to copy his works, including his most famous statue of the Reclining Pauline Borghese today in the Galleria Borghese, and their collaboration on numerous commissions was intense until Canova’s death in Venice, in 1822. His funeral was held in Rome’s Church of Santi Apostoli.

Afterwards Tadolini, whose most famous works are the statue of St. Paul in St. Peter’s Square and another of St. Francis de Sales in the Basilica, kept the studio, where he worked with his sons Tito (1828-1910) and Scipione (1822-1892), who took over the studio and passed it on to his son Giulio (1849-1918), who passed it on to his son Enrico (1888-1967), who sculpted the Tomb of Pope Leo XIII in St. John in Lateran.

At Enrico’s death his heirs sold the studio to the Benucci Antiquarian Gallery. Its artistic heritage consisted of about 400 works-of-art, between sketches, plaster casts, documents, and tools, which the Italian Government decreed could not be sold or moved. The studio remained closed for 36 years until it opened again in October 2003 as a bar/restaurant/and museum with all the “immovable” art, Museo Atelier Canova Tadolini.

The atmosphere here is similar to the nearby and older historic Caffè Greco on Via Condotti, but it serves full, reasonably-priced and delicious meals from a very varied menu of local and international specialties, as well as cocktails and snacks. I can heartily recommend the tonnarelli cacio e pepe served in a little basket made of baked cheese and the lobster Catalonia-style. There are also several rooms of various sizes decorated with yellow silk upholstery that are appropriate for private parties. Ask for a table under the gigantic plaster cast of Leo XIII Giving a Blessing in the Salone Giulio.