To talk about camp is therefore to betray it. […]

For no one who wholeheartedly shares in a given sensibility can analyze it; he can only, whatever his intention, exhibit it.

Susan SontagCatalogue: Camp: Notes on Fashion, Yale University Press, 2019

Andrew Bolton with Karen Van Godsenhoven and Amanda Garkinkel,

Introduction by Fabio Cleto

Fashion exhibitions have proliferated in many museums around the world, testimony to the growing audience interest for clothes, and the imaginary and real bodies that have worn, exhibited and performed them, and the attraction for those who have created and still create them. This proliferation is also testimony to a growing attention and interest towards Fashion Studies, a multidisciplinary field that is gradually affirming itself as a privileged platform to examine in depth the dynamics of identity, gender, race and class, and the impact fashion has had on culture, economics and aesthetics.

Among the spaces where fashion is exhibited, some museums have had a special role, for both the history of the city in which they are located and for their international context and role as transmission belts for the way fashion is looked at, interpreted and displayed. The Metropolitan Museum of Art and its Costume Institute have, of course, a very special and prominent role in this complex and multilayered history. And above all, its blockbuster annual exhibitions, which open new windows not only on how to look at fashion, but also on how to exhibit and receive it, are much awaited and visited. I think, in fact, that it is crucial to add this level of accumulated experience when one considers fashion and fashion exhibitions.

We can find several points of contact that unite the experience of an urban space, public or private, a visit to a museum, and worn fashion, lived and imagined. At all these levels, we need to consider certain qualities that have something to do with experience which, as the film theorist Francesco Casetti suggests, in referring to the filmic experience, are “embodied”, “embedded,” and “grounded.” There is a parallel between the filmic experience mediated by the camera and the fashion experience mediated by an object, a garment that literally dresses our body. In other words, the fashion experience cannot be separated from the body (embodied), from culture (embedded), and a situational context (grounded). To this, we must add the level of imagination and utopian fantasy. In the cognitive act determined by experience, the imaginary garment or “mental garments” are not less real than those that are actually worn.

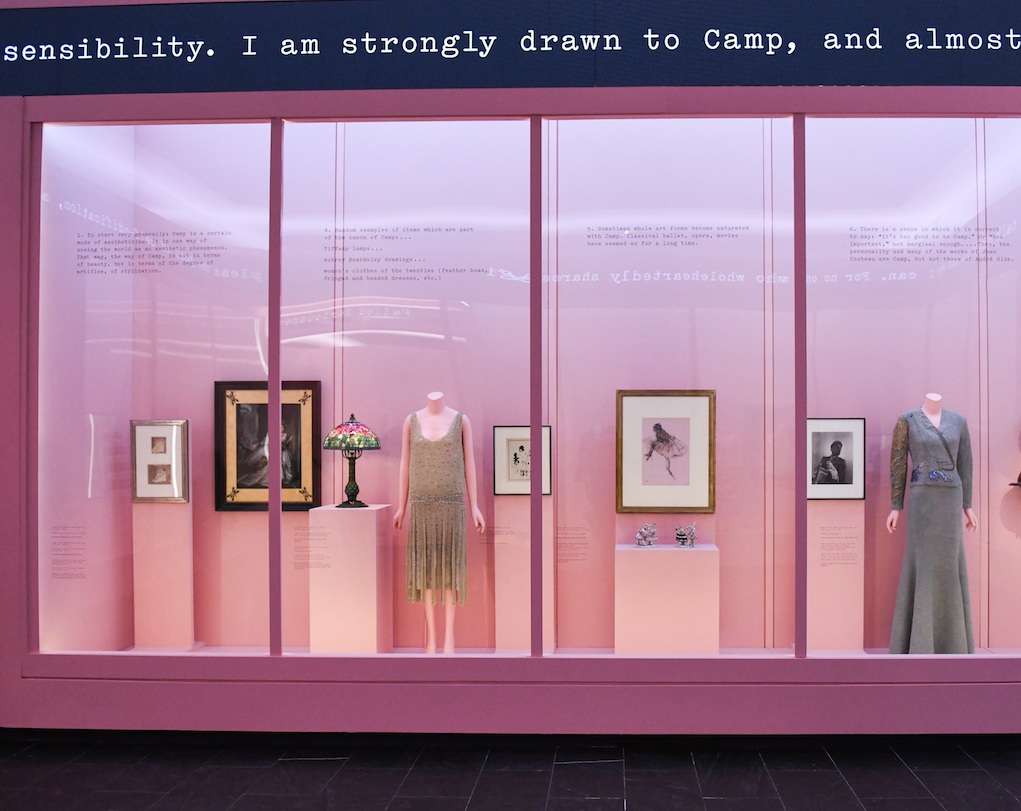

This preamble is the threshold that leads me to reflect on “Camp,” the current exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum, curated by Andrew Bolton, which poses a number of important questions for our contemporary culture. The exhibition is more “food for thought” in an everyday in which we are bombarded by social media and fast-consuming images and words.

Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, BFA.com/Zach Hilty

The best, most worthwhile exhibitions are challenges to definitions, although what underlies them is always a strong concept. In this case, the concept feeds off and is grounded in, both a challenge and an interrogation. But let us go step by step. The exhibition reopens the debate on “Camp,” that started with the well-known and controversial essay by Susan Sontag. The essay, although at times making contradictory statements, poses important questions for both the time it was published–the early sixties–and for our present cultural and political climate.

The neuralgic points that are addressed and translated in the exhibit reside in the impossibility of defining Camp, and therefore incapsulating it in a box or giving it a clear-cut definition as if in a dictionary. Although Camp can de declined as a verb, a noun and an adjective, as is underlined by the exhibit, it does not have a tangible definition. By nature, the term itself escapes definition, inscribing itself rather as a space of tension, of encounter, of clash and of a theatricalization of reality and even of gender and identity, as they are commonly received by societal and normative expectations.

In her essay, Sontag introduces the concept of “Camp sensibility.” In the volume containing her camp essay, in fact, the essay on Camp is followed by one “On culture and the new sensibility,” an important essay that examines in depth the questions posed in “Camp”: namely, the distinction between: “’high’ and ‘low ’(or ‘mass’ or ‘popular’) culture, which is based partly on an evaluation of the difference between unique and mass-produced objects.[…] The works of popular culture (and even films were for a long time included in this category) were seen as having little value because they were manufactured objects…” (297).

Sontag emphasizes not only this feature of Camp, but also the fact that it had manifested itself in high culture and literature, as shown in the cause célèbre of Oscar Wilde, included, of course, in the MET exhibit along with his wonderful literary references. It was Oscar Wilde, affirms Sontag, who had formulated an important feature of Camp sensibility by embracing the idea that all objects could have similar value, but adding to this concept the important role of lived experience: “He [Wilde] announced his intention of ‘living up’ to his blue-and-white china, or declared that a doorknob could be as admirable as a painting. When he proclaimed the importance of a necktie, the boutonnière, the chair, Wilde was anticipating the democratic esprit of Camp” (289).

“Camp” is a self-reflection, an act of rethinking the objects, including those of the everyday that may seem devoid of color, bringing them to the fore within discourse and enabling a performance that is attentive to details and artifice. In this way, objects are perceived under a magnifying lens. Sontag mentions in her essay the work of Federico Fellini in La Dolce Vita, where he transforms the character of Anita Ekberg into a self-parody of her role as a Hollywood actress in Rome. But we must say that probably, there are many other instances in which Fellini translated Camp aesthetic at its best. This happens in his parodic and grotesque moments and in the ways he treats costumes and bodies. In fact, as Sontag tells us, Camp sees everything in quotation marks.

Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, BFA.com/Zach Hilty

But this practice also extends to the concepts of gender and identity, as well as to the act of quotation, assemblage and the bending of forms. In doing so, the very concepts of normality and accepted aesthetic codes are undermined by pointing at a redefinition and interrogation of the forms of objects and bodies. Camp does not exclude beauty. Rather, it interrogates it along with the experience of the gaze and the body. Following these lines, it is not surprising to find Balenciaga and Moschino in the exhibition– a kind of an odd couple; or the Ferragamo 1938 rainbow shoe and a Gucci sneaker.

This process of transvestitism, which is also typical of fashion, although maintaining its features of joy and innocence, has a political connotation that is embraced by Bolton, but it is a connotation that Sontag rejects: “Camp sensibility is disengaged, depoliticized—or at least apolitical.”

In this process of re-definition of style and form, Sontag does not see a political dimension, whereas Bolton’s interpretation underlies the political aspect and potential of Camp. In her essay, Sontag does not go in depth, for instance, into the homosexual culture that had expressed the Camp sensibility–one of the points that emerges most strongly from the MET exhibit. Although there are several presences including Andy Warhol’s factory, the 1960s New York Avant-garde and the underground experiences of artists such as Jack Smith, Kenneth Anger etc. are absent from the show.

In another essay contained in the same volume, Against Interpretation, Sontag defends the Avant-garde film by Jack Smith, Flaming Creature, from censorship. Here she states that, “The texture of Flaming Creatures is made up of a rich collage of ‘camp’ lore. […] The vocabulary of images and textures on which Smith draws includes pre-Raphaelite languidness; Art Nouveau; the great exotica styles of the twenties, the Spanish and the Arab; and the modern ‘camp’ way of relishing mass culture” (Sontag, 1964: 31). Indeed, it is well worth watching these films again–Normal Love by Jack Smith, shot after Flaming Creatures, or Chulum by Ron Rice, or Lupe by Rodriguez- Soltero.

This past Spring, I included Normal Love in a course I taught at the CUNY Graduate Center, along with others I saw at the Miami edition of the Fashion in Film Festival. They are some of the most sophisticated renditions of the challenge offered by Camp in creating a layered aesthetic dimension that plays joyfully with the borders of identity, gender and its masks. Film critic Ronald Gregg is right when he says that Jack Smith, Mario Montez, Kenneth Anger and their group of friends and collaborators appropriated Hollywood excesses in order to construct and perform their utopian camp phantasies (Gregg: 2016). Certainly, their costumes were invented and made in their thrifting tours because they did not have a budget or even enough money to live sometimes.

And yet as artists they did not give up on making themselves visible, inventing a new cinematic language and playing with excess and glamour even to the point of glamourizing their sordid reality. They also offered a parody of so-called normality. But they have left, of course, no trace of their costumes and veils, present now only in the films that have survived.

So, anyone who wanted to find in the MET exhibit a clear-cut definition of Camp will be disappointed. However, what they do find is a rich repertoire of clothes, costumes, accessories, art objects, books, manuscripts, recorded voices of scholars discussing the theme; including the Italian philosopher Fabio Cleto, who has also contributed to the catalogue. In the room dedicated to Sontag, we can hear the sound of the typewriter that mimes the process of writing, of its rhythms and of the thought that beats the tempo.

I would like to conclude these reflections with a detail that was for me a nice discovery. I am not sure it has any value, but it certainly captured my curiosity and enriched my own experience of visiting the exhibit; indeed, my two visits. I went when the exhibit opened and while I was walking through the rooms, a few people in front of me were complaining that they could not read the black captions on the transparent surface of the glass cases. On my second visit, always with many visitors, I wanted to spend more time reading the captions and by mere chance, because there were people in front of me, I moved and positioned myself diagonally to the case. Magically, I was able to clearly read the captions. Then I tried to take a few steps moving to different angles and noted that looking at the caption from the front the view was blurred, but if you move into an oblique position, it was possible to read everything clearly. I have no idea if this was done intentionally by those who worked on the exhibition, but I must say that this detail was a lot of fun and a witty engagement with the body of the visitor. It reminded me of Sontag’s words: “Not only is there a camp vision, a Camp way of looking at things” and “Camp sees everything in quotation marks,” it was a “hidden” suggestion to abandon the familiar perspective and try to acquire another angle that allows us to rethink the strategic nature of identity and its constant process of re-definition.