I’d like to say here and now that even to be a “mere background” singer to a Pavarotti is exhilarating, and to become the diction coach of the chorus that supported the stars of the Metropolitan Opera House–such as James McCracken, the great baritone Dmitri Hvorostovsky, Maria Guleghina, Samuel Ramey, Carlo Bergonzi and Salvatore Licitra– is a memorable life experience. How was I fortunate enough to enjoy these experiences? My love affair with opera started when I was 6 years old and watched my first opera, Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci, on television. I was immediately enchanted and hooked forever. At the time, I watched, completely mesmerized, never imagining that one day I would have such a central role in the production of world class operas. From my living room to the stages of Carnegie Hall and Lincoln Center, my path, both musically and linguistically, was richly paved.

I’d like to say here and now that even to be a “mere background” singer to a Pavarotti is exhilarating, and to become the diction coach of the chorus that supported the stars of the Metropolitan Opera House–such as James McCracken, the great baritone Dmitri Hvorostovsky, Maria Guleghina, Samuel Ramey, Carlo Bergonzi and Salvatore Licitra– is a memorable life experience. How was I fortunate enough to enjoy these experiences? My love affair with opera started when I was 6 years old and watched my first opera, Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci, on television. I was immediately enchanted and hooked forever. At the time, I watched, completely mesmerized, never imagining that one day I would have such a central role in the production of world class operas. From my living room to the stages of Carnegie Hall and Lincoln Center, my path, both musically and linguistically, was richly paved.

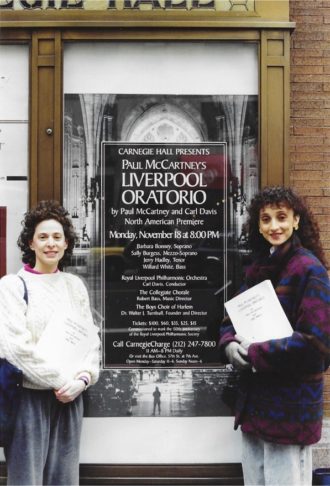

Some years ago, I was a member of the famed Collegiate Chorale (now called MasterVoices). Our conductor, the late Robert Bass, transported us from the realm of the standard choral repertoire to the majestic world of theatre at its best – opera in concert on the stage of Carnegie Hall. From Respighi to Ponchielli to the quintessential Verdi, the walls of Carnegie resounded with the voices of 150 strong, supporting a stellar cast.

Knowing that I had a solid musical preparation and spoke Italian as well, Robert Bass invited me to be the Italian diction coach. Although I felt elated at the mere prospect of this, I was initially too intimidated to accept immediately but agreed to review the text. Once I held Verdi’s Nabucco in my hands, I immediately knew that this was something that I simply had to do; this journey was the marriage of the two subjects I love most, music and the Italian language.

For several years afterward, eight to be exact, each chorale season included one opera in concert. I would receive the score at the end of the prior season, which would usually give me approximately eight months to study and prepare before rehearsals would officially commence. During that time frame, I literally lived, ate and breathed opera, listening to the designated work every single day and carrying the score with me at all times, so I could glance at the pages and continue memorizing the lines even in the midst of some brief, quiet moments during the course of a work day.

My own preparation was only the first step. In the next stage I would have to pass on the fruit of my study to each section and member of the chorale (sopranos, altos, tenors and basses), by creating a recording that would then be distributed to each individual. During these recording sessions, I would read the text to the rhythm of the music, as my voice was superimposed over it. This then became sacred as a bible to the chorale members, and they would frequently say such things as, “I listen to your voice every day as I drive to and from work and do my errands.”

While immersed in the learning process, I was gradually developing a methodology that I would implement once rehearsals would begin. One thing was certain. There was a lot more to it than imparting the correct pronunciation of Italian words. Of course, it had to be that, but there was so much more! Rehearsals would always begin with vocal warm up exercises, which incorporated the five important elements of any Italian word – the vowels (a, e, i, o, u). By adding a consonant before each vowel, the essential sounds produced (ma, me, mi, mo, and mu) prepared them for virtually all of the Italian sounds they would have to produce as they sang the opera. I would then continue by speaking the text of the musical sections that Robert would be covering that evening, delivering each phrase as if I were in a theatrical play, to have the chorale members understand the flow of the language and the correlation between the spoken and sung verse. After, I would take the phrase apart to emphasize the vowel pronunciations of the words so that they could make markings in their score to guide them when practicing on their own. All this, plus the use of the study tapes proved most beneficial and fruitful.

Once they were confident in the pronunciation, I would begin coaching them on the plot. They were, of course, all musically savvy, but revisiting the storyline through intent, tonality, phraseology, and dynamics broadened their perspective and brought it to life. I knew that the mere mimicking of correct pronunciation would long be forgotten, whereas the comprehension of it would not only enhance it to perfection but lend theatrically to the performance, and this was essential in my teaching process. I wanted them to realize that although they were a collective entity, each one was an integral part of the performance, as were the soloists.

The intensity of this process educated me to the brilliant structure of opera libretti and the poetic form they embrace. As I read and committed to memory, words, phrases and passages, I discovered that the music was already in the text. The truth of this is proved by the fact that Verdi himself always demanded a perfect libretto first, over which he would then drape the music with the most exquisite orchestration of notes, culminating in a body of work that perfectly melded the musical and dramatic components.

My method of coaching Italian diction in the context of dramatic interpretation was validated many times, as in one memorable case when, while preparing the chorale for Verdi’s Macbeth, the conductor asked me to take over, out of sheer frustration, when he wasn’t getting precisely what he wanted out of the singers. When he resumed, he paid me the highest compliment as the chorale was finally able to bring together clear diction and dramatic moment. When he turned to me and asked in disbelief, “How did you do that?” was a great moment in my life and I knew then that my love of the Italian language and opera was indeed a marriage made in heaven.