If you ask even some experienced art historians about the identity and works of Jacopo Comin (September 29, 1518-May 31, 1593), they might conceivably draw a blank and yet he was one of the Venetian School’s greatest painters and probably the last great painter of the Italian Renaissance. His huge works are characterized by their liberties with traditional iconography, muscular figures Michelangelo-style, dramatic gestures, perpetual motion, energetic brushstrokes, spectacular use of perspectival space in the Mannerist style, and special lighting effects making him a precursor of Baroque art, while maintaining the colors of the Venetian school. Due to his phenomenal non-stop drive this prolific artist, for he painted over 600 mostly huge canvasses, was called “Il Furioso”.

In his youth he was also called “Jacopo Robusti”, because his father had defended the gates of Padua in a rather robust way against the Imperial troops during the War of the League of Cambrai (1509-1516). Somehow his real name “Comin”, meaning the spice cumin in Venetian dialect, was only recently discovered by Miguel Falomir, the curator of the Prado in Madrid, and made public during the only retrospective until then of Tintoretto’s work, held there in 2007.

The eldest of 21 children, this hot-tempered ambitious non-conformist genius, incapable of love except for his work for he closed all but one of his daughters in convents and banished all but two of his sons, was born in cosmopolitan Venice and scarcely ever traveled elsewhere. His father Giovanni was a dyer or tintore; hence his son was also nicknamed Tintoretto, little dyer or dyer’s boy, by which he is known today.

Tintoretto was a born painter. His father, noticing his precocious gift, took him to Titian for training, but, according to legend, the great master, jealous of his student’s talent, sent him home after only ten days and from then on gave him the cold shoulder, although Tintoretto, otherwise self-taught (most unusual for his time he was never apprenticed to a workshop), always remained a professed and ardent admirer of his first and only “teacher”, whose contempt he ignored. Tintoretto’s haughtiness, audacity, and willingness to work for little money so as to get commissions, however, made him unpopular in the fiercely competitive Venetian artistic community. According to his biographical article in Wikipedia, Tintoretto’s “noble conception of art and his high personal ambition were evidenced in the inscription which he placed over his studio Il disegno di Michelangelo e il colorito di Tiziano (‘Michelangelo’s design and Titian’s color’).”

If we ignore the thematic exhibition of his portraits held in Venice in 1994, the last previous exhibition in Italy of the great Venetian master’s work had been held in 1937…” until the splendid one held in Rome’s Scuderie’s in 2012 and curated by the controversial art historian Vittorio Sgarbi. In all fairness the reason for this “oversight” is the impossibility to transport his enormous canvasses.

For his 500th birthday museums in Venice, Washington D.C. and New York seem to be apologizing for this past inattention. His birthplace is celebrating with two major exhibitions from September 7, 2018 to January 6, 2019. The exhibition at Venice’s Gallerie dell’Accademia, (Il giovane Tintoretto or The Young Tintoretto) includes some 60 works from the first ten years of the artist’s activity, from 1538 when documents report he was working independently at St. Jeremiah until 1548, the date of clamorous success of his first public work Il Miracolo dello Schiavo or The Miracle of the Slave painted for the Scuola Grande di San Marco, but now in the Galleria. Twenty-six of the exhibit’s some 60 works belong permanently to the Galleria; the others are on loan from the Louvre, The National Gallery in Washington, the Prado in Madrid, the Galleria Borghese in Rome, the Kunsthistorische Museum in Vienna, the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest, the Fabbrica del Duomo in Milan, the Courtauld Gallerry in London, the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut as well as from private collections.

On display in chronological order the works here attempt to investigate Tintoretto’s artistic development since he did not have a mentor or learn in a specific workshop. Rather Tintoretto acquired and transformed his models to develop his own dramatic and revolutionary style thanks to the suggestions of fellow painters, a generation older: Titian, Pordenone, Bonifacio de’ Pitati, Paris Bordon, Francesco Salviati, Giorgio Vasari, Jacopo Sansavino, whose works are also on display here to illustrate their influence on Tintoretto’s development. Also on display are paintings and sculptures of Tintoretto’s contemporaries, also working in Venice: Andrea Schiavone, Giuseppe Porta Slaviati, Lambert Sustris, and Bartolomeo Ammannati.

The masterpieces by Tintoretto on display in “Young Tintoretto” include “The Conversion of St. Paul”(c.1544) on loan from the National Gallery in Washington and “Apollo and Marsia” (1543-44) on loan from the Atheneum in Hartford, both displayed in Italy for the first time, “Christ among the Doctors” (1540-1) from the Veneranda Fabbrica del Duomo di Milano, and the “Supper in Emmaus” (1537-47) from Budapest, not to overlook ceiling from the Palazzo Pisani (1541-2) in Venice, now in Modena’s Gallerie.

Venice’s second exhibition, “Tintoretto (1519-1594)” held in the Doge’s Palace, the permanent home of several of his monumental canvases, “focuses on the most fruitful period of his art,” recounts the exhibition’s press release, “from his full affirmation in the mid-1540s to his last works.

“With fifty autograph paintings and twenty drawings by Tintoretto”, continues the press release, “together with the famous cycles painted for the Doge’s palace between 1564 and 1592-visible in their original position-the exhibition showcases all the visionary, bold and wholly unconventional painting of Jacopo Robusti… ‘Like a single peppercorn capable of overcoming ten bunches of poppy’ as his playwright friend Andrea Calmo described him, Tintoretto knew how to challenge the tradition embodied by Titian, overwhelming it and choosing to innovate, not only with daring technical and stylistic solutions, but also with iconographic experiments that marked an important turning point in the history of Venetian painting in the sixteenth century.

“An extraordinary storyteller, skilled director of painted actions and sophisticated colorist—he who used the full range of pigments available in the Venice of his time—Tintoretto reveals himself as a fascinating interpreter of all the different genres he explored, from religious subjects to great history paintings, and from portraiture to profane and mythological themes.” Loans come from private collections and museums all over the world: London, Paris, Ghent, Lyons, Dresden, Otterlo, Prague, and Rotterdam, Chicago, New York, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C..

Of special note are five extraordinary works from the Prado which include “Joseph and the Wife of Potiphar” (c. 1555), “Judith and Holofernes” (1552-1555), and the recently restored over 5 feet long “The Rape of Helen” (1578), painted for the Gonzagas; from London’s National Gallery’s “The Origin of the Milky Way” (1575); from the Staatliche Museen in Berlin “The Portrait of Giovanni Mocenigo” (1580); from the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna perhaps his greatest masterpiece “Susanna and the Elders” (1577).

“Among the religious masterpieces,” explains the press release, “a renewed quality stands out, revealed by the recent restorations [18 of which and not to mention the artist’s tomb are thanks to Save Venice], of the altarpieces of San Marziale and of the Ateneo Veneto. And likewise for the large canvases of his last years, in which the hand of his son Domenico and of his workshop can be discerned, but which preserve intact the whole visionary approach of the great Tintoretto in the conception of the composition.”

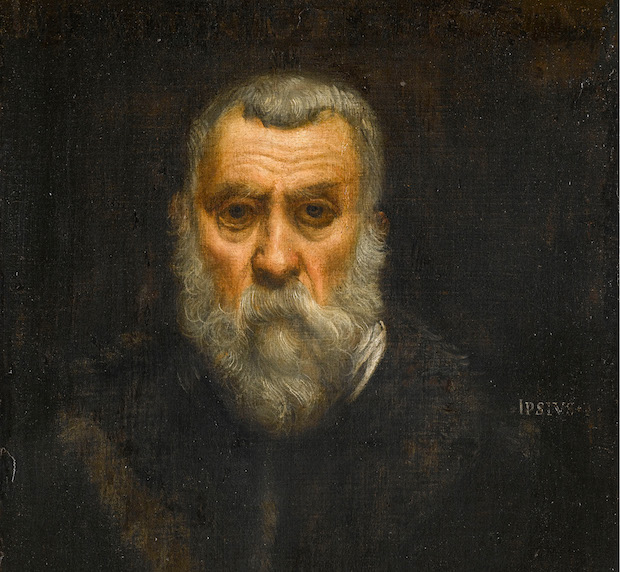

The Doge’s Palace exhibition opens and closes with two self-portraits. One was painted at the beginning of Tintoretto’s career and is on loan from the Philadelphia Museum of Art; it has been defined by the curators as the first “autonomous” self-portrait in European painting. The other is on loan from the Louvre.

From March 10-July 7, 2019 many of Tintoretto’s works on display in the Doge’s Palace will be on display in the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C, the very first overseas blockbuster exhibition dedicated to this Venetian genius: “Tintoretto: Artist of Renaissance Venice”. The curators of both these exhibitions are two American scholars, great connoisseurs of Tintoretto, Robert Echols and Frederick Ilchman who, again the press release tells us, “for years have concentrated their research on drawing up a catalog raisonnée of Jacopo’s work.

There are more than 700 permanent works by Tintoretto spread all over Venice. Aside from the Galleria and the Doge’s Palace, other Tintoretto venues include the Scuola Grande di San Marco, the Scuola Grande di San Rocco, Museo Correr and many churches: San Cassiano, San Geramaia, San Giorgio Maggiore, Santa Maria Mater, Santa Maria della Salute, and Santa Maria dell’Orto, Tintoretto’s Parish Church, where he, his son Domenico, and his daughter Marietta, both talented artists in their own right, are buried, not to mention Tintoretto’s house nearby on the Fondamenta dei Mori, also in the sestiere (neighborhood) of Cannareggio.

Thus there are many works by Tintoretto in Venice all the time, but being able to admire those on loan from so many faraway locations is special as is the exhibitions’ catalog published by Marsilio (53 euros), a souvenir of a unique unrepeatable event.

“It seemed to me that I had advanced to the uttermost limit of painting”, wrote Henry James, after seeing Tintoretto’s paintings in San Cassiano, “that beyond this another art-inspired poetry-begins, and that Bellini, Veronese, Giorgione, and Titian, all joining hands and straining every muscle of their genius, reach forward not so far but as far as they leave a visible space in which Titoret alone is master […]. No painter ever had such breadth and such depth… Titian was assuredly a mighty poet, but Tintoret, well, Tintoret was almost a prophet.”

To learn more about this phenomenal artist read the novelist Melania Mazzucco. She wrote a well-documented prize-winning biographical novel of Tintoretto, La Lunga Attesa dell’Angelo (2008) (The Last Confession of Tintoretto) and a second profile of his whole family, Jacomo Tintoretto & I Suoi figli (2009) featuring his favorite oldest daughter Marietta (1556-90), who, born-out-of wedlock from a German prostitute, became a skillful portrait painter and musician.