First presented in Florence at the Uffizi Gallery from May 8 to July 29, the small (only 7 artworks) exhibition “Pontormo: Miraculous Encounters” is on at the Morgan Library & Museum until January 6th, 2019. From here it will travel to the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, where an expanded version (10 artworks) will be shown from February 5 to April 28.

Although not a household name like other artists of his times, Jacopo Carucci (1494-1557), nicknamed Pontormo after his birthplace Pontorme in Tuscany, was one of the most extraordinary Mannerist painters, portraitists, and draftsmen of 16th-century Florence, where most of his works still remain. Many consider his large altarpiece canvas for the Brunelleschi-designed Capponi Chapel in the Florentine church of Santa Felicità, portraying The Deposition from the Cross (1528), to be Portormo’s surviving masterpiece. As the exhibition’s catalog tells us, it is believed that the old man who observes the scene from an almost hidden position at the painting’s far right is a Pontormo’s self-portrait in the guise of Joseph of Arimathea. Also on display here is the self-portrait’s red-chalk preparatory sketch.

Wundram.

“[Pontormo’s] work represents,” Wikipedia recounts, “a profound stylistic shift from the calm perspectival regularity that characterized the art of the Florentine Renaissance. He is famous for his use of twining poses, coupled with ambiguous perspective; his figures often seem to float in an uncertain environment, unhampered by the forces of gravity.”

In his biography of Pontormo in his Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects, a second edition copy (1568) of which is on display opened to Pontormo complete with portrait, Vasari describes him as withdrawn, disheveled, and neurotic, if not paranoid. Except for a trip to Rome, to see Michelangelo’s work especially the Sistine Chapel, which afterwards certainly influenced his art, Pontormo spent most of his life in Florence, often supported by Medici patronage. Haunted faces and elongated, seemingly floating bodies are characteristic of his works. By the end of the 1520s, he had created one of his most moving and groundbreaking paintings, the Visitation. The focus of Pontormo: Miraculous Encounters, this recently restored (2013-14) masterpiece, has traveled to the United States for the first time.

Pontormo painted The Visitation for the Pieve dei Santi Michele e Francesco, a small parish church located in Carmignano, a small picturesque town some 20 miles west of Florence. Until this exhibition it was only accessible by visiting the church. It was probably painted between 1529 and 1530 when Florence was besieged by the armies of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (1500-58), who sought to capture Florence, overthrow the newly established Republican government, and return the Medicis to power. So instead of his usual Medici patrons, the Pinadori family, supporters of the Republic, who owned a villa in Carmignano, probably commissioned the Visitation.

“Standing over six feet tall,” Morgan’s press release tells us, “[the Visitation] depicts the intense moment of encounter between the Virgin Mary, shown at left, and her cousin Elizabeth, who reveal to each other that both are pregnant…According to Catholic tradition, the visit, recorded in the Gospel of Luke [1:39-45], was believed to bring divine grace to both Elizabeth and her unborn child, who recognized the presence of Jesus.”

“Breaking with traditional iconography,” continues the press release, “Pontormo created a deeply personal version of the miraculous encounter…[He] eliminated most of the narrative details of the encounter and instead focused on the two sacred figures, accompanied by their female attendants, in fluttering garments and with their barefoot heels raised in motion…In this altarpiece, Pontormo captured both the human and spiritual elements of the encounter in a composition that has influenced artists from de Chirico to Bill Viola.” An engraving by Dürer of “Four Naked Women” dated 1497, which Pontormo had almost certainly studied and is on display here, probably influenced the artist’s layout of the Visitation.

During the altarpiece’s restoration, again continues the press release, “the removal of old layers of varnish and overpaint uncovered details that had become invisible over time, such as the two male figures [who, according to the exhibition’s splendid catalog ($40.00), are “likely intended to represent Joseph and Zechariah, the husbands of the pregnant cousins”] and the donkey on the left in the background. Technical analysis revealed that Pontormo had used a charcoal underdrawing to transfer the composition from the preparatory drawing on paper [the only one known, also on display here] to the surface of the panel.”

According the website www.visittuscany.com Carmignano’s Visitation is Pontormo’s third and last variation of this theme. “The first was made for the Carro della Moneta which depicts the womens’ embraces [1514] and is conserved in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence, while the second is located in the church of the Santissima Annunziata, also in Florence. It’s a fresco, also from Pontormo’s early period, painted between 1514 and 1516.

Exhibition highlights include the Portrait of a Young Man in a Red Cap and the Portrait (c.1530) of a Halberdier (only at the Getty) for, besides his religious subjects, Pontormo was a much-admired portraitist (only 15 survive today, 13 being in Italy). Although known to scholars through documents and engravings, the first-mentioned was thought lost until its rediscovery in a private collection (the Earl of Caledon’s) in England in 2008. It was bought by J. Tomlinson Hill, a New Yorker, generous philanthropist and partner in the asset management group Blackstone, in 2015 for $48 million dollars. On public display here for the first time, it was recently restored. Its subject is believed to be Carlo Neroni, a young aristocrat who was a volunteer in the Republican army against the Medici. Its date may coincide with his marriage to Caterina Capponi, daughter of a rich merchant for he is wearing a ring and holding possibly a love letter in his right hand. More likely, however, since Carlo Neroni would have been only 19-years-old in 1530, and also because of the terrified and worried expression on his face the letter in his hand is connected to his Republican politics and could contain a secret message. Unfortunately, its text is mostly hidden or illegible.

The Portrait of the Young Halberdier was bought by the J. Getty Paul Getty Museum in 1989 for $32.5 million. Besides the finished portrait on display is a red chalk preparatory drawing on loan from the Uffizi Gallery (only at the Getty). The halberdier’s identity is contested. “Is he the young Francesco Guardi (1514-1554), who in a Florence besieged by the imperial troops who came to restore the Medici to power, had himself portrayed as a vigorous defender of Florentina libertas?”, questions the catalog, “Or is he the young Cosimo de’ Medici(1519-1574), son of Giovanni delle Bande Nere, who from scion of a cadet branch of the family was unexpectedly elevated to the rank of Duke after his cousin Alessandro was assassinated? Both hypotheses are based on passages from Vasari’s Life of Pontormo.” The catalog then goes on to cover the attribution of several art historians, but the Halbedier’s likely date and its several stylistic similarities to the Portrait of a Young Man in a Red Cap favor Francesco Guardi.

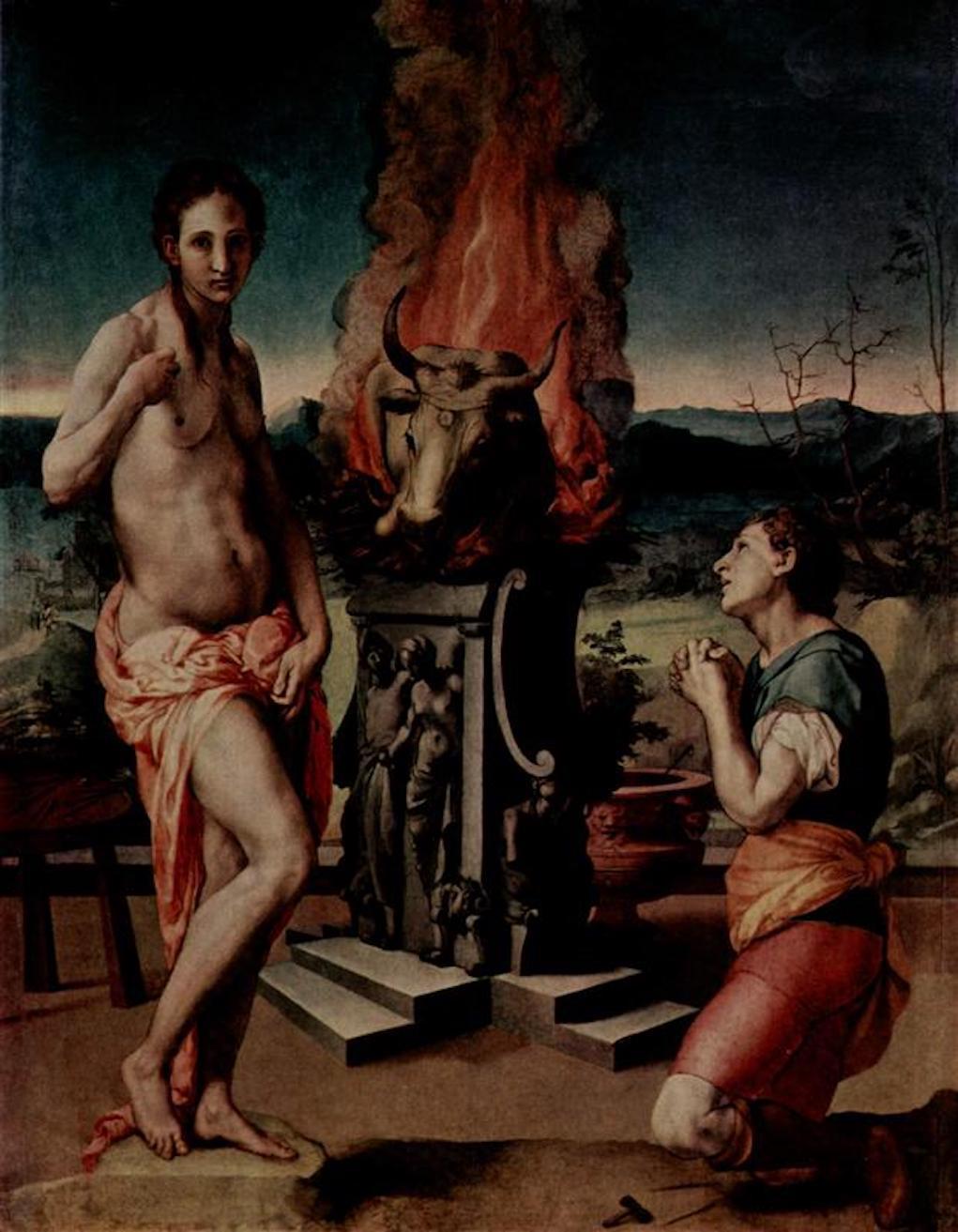

According to the catalog, regardless of the halberdier’s true identity, this portrait by Pontormo “was a key model for later paintings by his pupil Bronzino…[ (1503-72, who] was quite familiar with the Halberdier, since he had painted the “cover” depicting the myth of Pygmalion, [only at the Getty)]… Although initially [it] was considered to have been completely or in large part painted by Pontormo, in 1955 [art historian] Craig Hugh Smyth persuasively made the case for Bronzino’s authorship.” Nonetheless Venus’s face bears a strong resemblance to that of Pontormo’a Halberdier as does the kneeling Pygmalion to a drawing by Pontormo of a kneeling St. Francis in the Uffizi Gallery. For it seems that Pontomormo often gave his student Bronzino drawings that he then rendered in paint.