Click. I rewind the tape; a decade, perhaps more. My first year of high school, the sleepy hinterlands of the Po Valley, and our first dinners without parents. My best friend and classmate telephones to invite me to a birthday party. She senses that I am cold and distant, as usual. You can’t tell us no again… not this time!, she yells, clearly annoyed, into my prehistoric Panasonic phone, which is covered with punk stickers. Do you remember that outburst, Caterina? And my embarrassment, my wavering voice? I dodge the invitation by feigning the sort of aptly-timed illness that no one believed from me any more and I go back online, free from bothersome social commitments. I was fourteen years old and I loved Alice Cooper and Overend Watts. My geeky provincial adolescence felt barren. Only in isolating myself with my Beatles and my Stones would I find an oasis of happiness. My schoolmates were childish and immature and considered me a freak of nature; I was a glam rocker over three decades past its time, surrounded by fans of Rihanna and Shakira. There was no room for me and my suspicious eccentricity; not for my hair curls or my outmoded top hat, nor my exaggerated stage make-up that hid my insecurities. I paid a very high price for my differences.

David Bowie and Marc Bolan were heroes for me and for Jude, a Finnish transgender boy whom I had met on a now-defunct social network. We loved to dress up – me with unlikely leopard jeans hugging my boyish hips, him with multicoloured fur coats and platform boots that were so out-of-place in Helsinki. We would joyfully sing hits by our favourite artists with carefree abandon. I could have loved, girl, like a planet… Jude crooned, his voice sweet enough to break one’s heart. We knew all of them and Tony Visconti, the skillful and limelight-shirking producer able to stem the excesses of his prime donne, was a point of reference for us. Jude and I knew we did not have a place in the world – that we were freaks – yet a voice inside us kept telling us that our music would keep us alive. We spent hours on the telephone, our English already fluent and vaguely cockney despite our age. We swore to ourselves that we would never betray our rock roots. With one blue and one green contact lens to simulate the appearance of Bowie’s eyes, a bold Bolder forelock and a small silver spider on one finger, I faced daily life with constant anxiety. There was no redemption for us and there was nothing cool about listening to T. Rex in Italy. The subdued sniggers in the school corridors come to mind.

And there I am just a few months ago, an adult now – it’s the day before my 26th birthday. I make a somewhat banal comment on a Facebook post of a mutual contact of ours and Tony accepts my friend request, which had been lying dormant for years among those from his tens of thousands of fans. Unexpectedly, given the difference in time zones, he is the first to wish me happy birthday. The sense of surprise makes me blurt out an uncertain, almost silly response. The English language does not distinguish between informal and formal you, so any set phrase that I try to come up with seems impudent. A few weeks later, in a small second-hand bookstore in Reykjavík, I discover an issue of Life magazine in a display cabinet off to the side, with a then-Princess Elizabeth radiant on the cover. The date of publication of the magazine, the 24th of April 1944, is the birthday of Tony. I don’t think twice about it, and give my remaining kronur to the bookseller, cramming the magazine into my handbag. Will I ever meet him? I doubt it, but I know I will always take the issue with me. I spend what remains of that Icelandic afternoon free from tours and excursions, instead meandering through the various vinyl stores in the city centre. A copy of Electric Warrior on the bookshelf catches my sight. Visconti is everywhere – in every album of my adolescence, in those magical lyrics and notes and arrangements.

It is not long after my return from Iceland that work serendipitously brings me to Manhattan. Tony graciously agrees to meet me for an interview. In the taxi, heading towards my appointment with him, I relive those tormented teenage years. I am not sure if I want to laugh or to cry – perhaps I just want to flee. Stuck in this mental plight as I was stuck in the traffic on 5th Avenue, I put in my EarPods and took refuge with the Smiths. When I arrive at the Japanese restaurant for the meeting, the door seems very heavy, and like the morituri, I have a big lump in my throat. I gaze inside; Tony is only a few metres from me, wearing the smile of a boy. He has a delightful way of smiling with his eyes, which I was already familiar with from weeks of studying his past interviews online. He seems glad to see me. I hug him awkwardly and together we wait for a table to free up. As an interviewer, I try to mask my emotions while I eat ramen, all without taking my eyes off him. We get to his studio, but in the few steps that separate us from the main entrance I manage to stumble into him. His strong hands catch me and stop me from falling to the pavement. Maybe it’s not real, maybe it’s only a dream.

We listen to Bowie together for an hour before waving goodbye. I brought a proper camera, but I only take a few pictures with my iPhone. I wish in hindsight I had taken more photographs, but perhaps my subconscious jealousy did not want to share the afternoon with anyone else. We talk of Morrissey, Mick Ronson and Holy Holy and their upcoming tour in the UK – the band performs Bowie’s work and includes Woody Woodmansey, the only surviving member of the original line-up of the Spiders from Mars, alongside Visconti on bass. Tony has anecdotes about everyone; a fifty-year career has made him an encyclopaedia of rock, yet he is still humble and laidback – the Italian-American Brooklyn boy that sought and found fame and fortune in England in managing some of the greatest of all time. Before parting ways, he autographs my copy of his biography with a lovely dedication. A few days later, in the airplane, unexpected turbulence starts to give me a panic attack and I clutch the book to my chest to relax myself. How many lives you have changed, Mr. Visconti!

Tony, thank you for the opportunity to interview you. Having you with us is a real honor for our publication. We Italians love to consider you one of us. Like many Italian-Americans of your generation, you have helped to make the USA great, and by reflection the land of your grandparents. What is your relationship with Italy, and in particular Naples and Rome – the cities from which your maternal grandparents and your paternal grandmother departed for Ellis Island? How much of you, of your character, would you attribute to your Mediterranean roots?

“I grew up in Brooklyn, New York. Many people on my street came from Southern Italy – Naples, Apulia, Calabria, Bari and Sicily. My mother, Josephine, spoke Italian with a Neapolitan dialect that she learned from her mother Rachel. My mother was born in Brooklyn, NY too while my grandmother was born in Afragola. Her father, Gennaro, was a tall, handsome man and was in the Army. My grandmother fell in love with him when she saw him in his uniform. He was also a farmer.

In Brooklyn, my mother and my grandfather only spoke Italian. He never learned English. My father, Anthony, never learned Italian and neither did I. We ate Italian food about five days a week. Fish on Friday, of course! My grandmother Rachel brought the recipes with her and my mother was an excellent student. She could easily cook a Sunday dinner for twelve to sixteen people if she started the sauce on Friday night.

The glue that held our family together was music. Both my parents could sing. My father had an average voice but he sang with gusto. He played the accordion. My mother had a beautiful contralto voice. About ten years ago I found recordings of her singing. O Maria, Torna a Surriento and O’ marenariello – and I wept! I phoned her and told her she could have been a professional. Her emotion was very real and her vibrato and intonation was perfect! Her reply was, “Oh, all Italian women can sing like that”!

Our little family moved in with my father’s parents, Nicholas and Elisabetta, in their three-storey house in Bay Ridge. Nicholas was born in New York in the late 1880s. He never learned Italian. You could call him a New York wise guy, but he was very lovable with me. He was a businessman and sold wholesale fruit and vegetables and paper bags. Gennaro was one of his clients. Nicholas played violin with Jimmy Durante, an Italian-American singer, actor, comedian and he met Al Capone when he worked in nightclubs. Elisabetta came from Tursi, in the province of Matera, Basilicata. Her father was a judge. Her mother was Albanian. In Brooklyn, my grandmother’s four Albanian cousins used to come to her house and sit around a table making gnocchi by hand, speaking in Albanian. My grandmother spoke Italian, Albanian and Greek in Italy. She leaned Spanish and a little bit of Yiddish after she came to New York. Her father sent her to school until she was fifteen years old. In Brooklyn, she used her education to write letters to be sent to Italy for illiterate Italians. She was a very colorful person – very direct and funny. She feared no one. My family’s culture was 50% Italian and 50% American. The best of both worlds”.

You were born in Brooklyn in April 1944 – more specifically Dyker Heights, the Italian-American neighbourhood. In what borough of New York do you feel most at home? How much have the areas of your childhood – Ocean Parkway, Red Hook – changed since then?

“When we lived in Ocean Parkway, we were the only Italian family on the street, I think. Most of the families were of Russian-Jewish descent. I was asked to light their stoves for cooking on Friday night, the beginning of the Sabbath. I haven’t been there since but I don’t think many Italians live there. There are still Italian families in Red Hook and Dyker Heights, but a lot of them moved to Long Island and Russian immigrants moved into those neighborhoods. When Italians became affluent they migrated to Long Island, Westchester County. Today you will find large groups of Italians in the Bronx and Staten Island. There is still the culture of Italian restaurants, mainly southern cuisine. Some are very authentic and the staff and their families always speak in Italian. I had never tasted northern style cuisine until I moved to London, where most Italian immigrants are from the North”.

England is your second home. The encounter with Denny Cordell, manager of Procol Harum and your mentor, changed your life. In this way the young bassist from Brooklyn became a producer. Was this due to skill, good fortune, or a bit of both?

“I was told by a psychic that I would meet an Englishman who would offer me a job in London. I had to go there – the music of the Beatles was a clarion call telling me to get to London as soon as possible! I met Denny Cordell by a water cooler in my publisher’s office. He said hello to me and I said, “You’re English!” – I knew he was the man! He was a successful producer in London. He played A Whiter Shade of Pale by Procol Harum to me, his production. I was blown away!

Then he played a demo of a song he was going to record in a hour, for Georgie Fame. He asked for a ten-piece band featuring Clark Terry on first trumpet. I asked to see the musical arrangements and he said he had none. I told him that there are strict union laws in New York and if he expected the band to write the arrangement it would take more time and money. He said in London they took all day to record one or two songs and it was very casual. I told him it was more formal in New York and sessions are only three hours long, with overtime penalties if it took more than three hours. I told him I’d help him and I wrote a one-page arrangement with the chords, the trumpet parts and the drum fills. The Xerox machine was a brand-new invention and we had one! I made ten copies and then we ran down West 48th Street arriving for the session a few minutes late. I handed out the parts and explained a few things to the musicians. Within a hour it all worked out just fine. Denny looked at me, very impressed, and offered me a job in London on the spot! He said he was going to interview a few more people to be his assistant, but in the end he picked me. It’s true I was at the right place at the right time – the water cooler – but I had the skills and American know-how he was looking for. A month later I was on a plane to London”.

Addiction saved you from the Vietnam War. Your blood tests revealed traces of drugs and a kind doctor with a German accent decided that you were not able-bodied. That day, as a young man, you decided to say goodbye to heroin. Do you believe in fate?

“Let me say first that addiction could have easily killed me. I experimented with heroin because all of the older jazz musicians I was hanging out with were using heroin. I overdosed twice, but luckily I was with people who knew what to do. Fate? Maybe I have a really good guardian angel. I managed to quit with methadone therapy which was very limited in New York at the time. Methadone was not used as it is now. Back in those days you could only get twelve tablets that would give you a week to kick the habit. It worked, but I got addicted again and went back to the same doctor for more pills. Heroin changes your blood chemistry, so you must take it to feel normal. It’s like a vampire needing blood!

Then I was drafted into the Vietnam War. The casualties were higher than World War II and the war was pointless. My best friend in high school died in the war. The USA was not under attack. I didn’t want to end my life this way, so I asked my older friends what I could do to get out of it. They said there are two ways. One was having heroin in your blood when you were being examined. The other was admitting to being a homosexual. I’m not a good actor, so I opted for heroin. I bought a small amount and injected myself the night before the examination. I was taken out of line after my blood test was positive for an opioid. It worked! I was interviewed by a psychiatrist with a thick German accent. He asked what drugs I took. I said, “All of them”. He looked at my long hair and asked me if I was a homosexual. I asked him, “Isn’t heroin enough”? He said okay, you are not Army material. Go see the social worker on the next floor. She was a very kind Jewish woman who liked me because I was honest with her. She asked me if I wanted to stop taking drugs and I thought to myself, “Is this a trick question? If I say no, will they call the police?”, so I said yes. I had to consent to going for group therapy which turned out beneficial for me. The group were young men and women. All the men were petty thieves stealing for drugs and the women were prostituiting themselves for drugs. Their stories were horrifying, especially the women’s stories. After six months of therapy, I met my first wife and brought her to see my group leader. I wasn’t sure if I was allowed to leave the group, but my group leader was convinced I was happy and safe with my sweetheart and wished us the best of luck. I never went back to heroin ever again”.

The premature passing of Marc Bolan, as sudden as it was senseless, brought an end to an era – one begun by the legendary Tyrannosaurus Rex with My People Were Fair and Had Stars in Their Hair… But Now They’re Content to Wear Sky on Their Brows. Nine years of world-wide success: the rise and fall of the glam icon par excellence. The timeless hits of T. Rex are still pillars of British rock. What memory do you have of Marc, forty years on from his death?

“Marc Bolan was a tragic figure. He was a genius. Music and poetry oozed out of him like nectar. He was a self-taught guitarist and developed a style all his own. You could identify his playing on other people’s recordings easily. He had one serious problem – his competitiveness. It would come out in strange ways, like exaggerating to the press about his successes. If we sold twenty-five thousand singles in one day, he would say we sold fifty thousand. When the press found out they made fun of him. He was short and this might have had something to do with it, possibly a Napoleonic complex. But I loved him like he was my brother. Together we took Tyrannosaurus Rex, playing very cheap acoustic instruments and small clubs, to the height of rock and roll fame and stadiums in three years. In the studio, it was always Marc and I controlling the recording process, he supplying the raw rock and roll. I wrote orchestral arrangements and sang backing vocals, and produced and mixed the recordings. Marc left an indelible stamp on rock. Today there is a little bit of T. Rex in every rock band. I miss him dearly”.

Almost everything has been said, written, and hypothesised of David Bowie. His private life often coincided with his public life. Everyone who knew him, even for a brief time, has since coughed up anecdotes on the man of a thousand faces and characters. Is there something that we don’t know about him and that you’d like to share with us? An “unedited” David Jones to whom you only had access.

“I met David Bowie in the same month I met Marc Bolan in 1967. I produced his second album, Space Oddity, and his last album, Blackstar, and a dozen in between. David had many professional faces giving him that awful name, chameleon, by the press. He was acting, those faces weren’t him. I can’t tell you much about him that you don’t already know. We can all agree that he was a super genius. In restaurants he often ordered food I would never touch, like brains, liver and kidneys. He said in Hong Kong, John Lennon dared him to eat monkey brains, but he stopped at that. He was a perfect gentleman. He wasn’t that wild! He knew lots of things about everything. I loved the long conversations we used to have. The day I met him in 1967 we talked and walked for at least six hours, then we saw A Knife in the Water directed by Roman Polanski. I miss David dearly. We spent a lot of his last year together in the studio”.

Which album among all those you have produced since the start of your career up to today is your favourite? And as the perfectionist you are, which doesn’t altogether convince you? Would you like to disavow any?

“My favorite album is probably Scary Monsters. Before starting a new album with David, we would joke about making our Sgt. Pepper’s. This meant a much bigger production than before that would stun the fans and critics alike. But with Scary Monsters we actually did that. I’m very proud of that production, all the crazy tricks we got up to, the great songs and musicianship. I love Heathen, The Next Day, Lodger and Blackstar. I’m so happy I remixed Lodger after more than thirty years. David and I never liked the mixes, which were done under bad conditions. I started remixing it in secret during breaks in Blackstar and played the first five remixed songs to him, which he loved. He didn’t live long enough to hear the rest of the album. I won’t disavow anything I produced but I would love to remix about thirty percent of my productions. I just like to keep trying to make music sound better”.

It’s impossible not to ask you about All the Young Dudes, the great present of Bowie to Mott the Hoople. It is of course the piece that saved the band and gave them a new direction, turning Ian Hunter into a star overnight. What made David gift such an iconic song to the boys from Herefordshire?

“It was a transitional time for David. He had just started to work with his new manager, Tony Defries, and Hunky Dory wasn’t the smash hit they were hoping for. When I heard the demo for All the Young Dudes, I couldn’t understand why David wasn’t doing it. Of course, he hadn’t invented Ziggy yet. Mott the Hoople had incredible good luck with this gift from David and they were able to sustain a successful career after that. They could have been a one hit wonder, but they weren’t! In later years David included All the Young Dudes in his stage shows. My group, Holy Holy, also plays it in our live set. It is a great song, a rock and roll anthem”.

New York has been the place of many tragic AIDS-related deaths in the musical world. Some of the more famous victims were Rachel, the beautiful transgender muse of Lou Reed in Coney Island Baby, or Jobriath and Klaus Nomi – the talented and tormented singers who passed away a few hours away from each other in 1983. Drugs were flowing everywhere and promiscuity was reaping its victims. Do the artists of today know better or is there still some tendency towards self-destruction? Can there exist genius and creativity without dissipation?

“I think most artists know better. There are less victims of AIDS in the music world. What I find disturbing is that there are more suicides in the music, theater and film worlds. This is, in many ways, a harder world to live in than it was in the Seventies. I think too much social media has something to do with it. A lot of young people also commit suicide for public shaming. This is so wrong”.

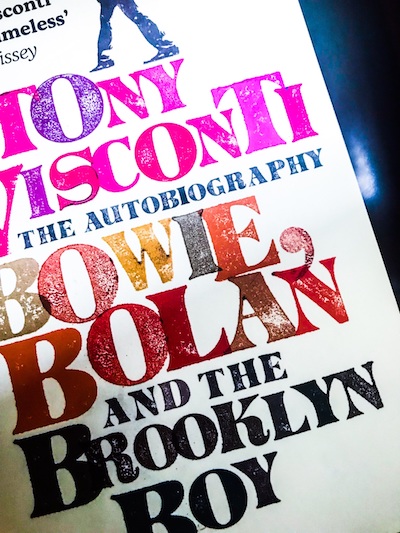

In your biography, Bowie, Bolan and the Brooklyn Kid, you recount various tales from your boyhood – the ukulele, afternoon guitar lessons, opulent Italian marriages at which you were playing for well-earned pocket money. Many boys today prefer talent shows and easy glory, disappearing after a couple of successful singles. What do you think of television programs like The X Factor?

“Although I loved rock and roll and I wanted to be the next Elvis or Buddy Holly, I was just so happy to be a working musician. At the young age of fifteen, I had a job and I loved my work. I didn’t want to play weddings and bar mitzvahs for too much longer, but for me it was a wonderful opportunity to become a better musician. Those old songs from the Forties were difficult to learn, especially Cole Porter songs. Listening to the orchestral arrangements of Frank Sinatra by Nelson Riddle was good training for me learning to arrange. I also read Beethoven scores like they were novels. In fact, The Beatles’ music helped me transition from a nightclub cabaret musician into a pop/rock record producer. Until I discovered George Martin I didn’t understand where it was I belonged in the music business. I don’t like programs like The X Factor. They are not about music, they are thinly-disguised reality shows. It’s all about the show, not the talent. They won’t pick a contestant unless they have a good backstory”.

Too many people tie the name of Tony Visconti to David Bowie and Marc Bolan, the two artists that have given you the most. But you have also produced albums of Iggy Pop, Morrissey, the Boomtown Rats, Richard Barone, a great artist who was never too popular in Italy, to name a few. Which has given you the most professional satisfaction?

“Apart from Bowie and Bolan, I love the work I’ve done with Esperanza Spaulding, Kristeen Young, Morrissey – I would like to work with him again, but there are too many obstacles. If you can find recordings of a group called Omaha Sheriff on Youtube, the two albums I made with them are my shining hours! I also loved working with the Flamenco Rock group, Carmen. In France I loved working with Les Rita Mitsouko, Louie Bertingac and Marc Lavoine. I love working in other languages. I can speak a little French and Spanish”.

What do you typically listen to for enjoyment – when you’re sitting at home relaxing, say? Who are your favorite artists past and present?

“I love jazz and classical music. We have two great radio stations in New York – WQXR for classical and WBGO for jazz. If I’m at thome I have one or the other playing all day long. My two favorite musicians are Beethoven and Miles Davis. In recent years, for pleasure, I listen to Kendrick Lamar and Mark Kozelek of Sun Kil Moon. David Bowie turned me on to both of them. I’m now friends with Mark.

I make playlists for my iPhone. I walk to my studio everyday. Because I’ve been rediscovering my Italian roots, I also listen to classic Italian pop songs. I adore Teresa De Sio. She is from Naples. I have two of her album. Toledo e regina is my favorite and I adore the song Catari’. She reworked classic Neapolitan songs with my old friend Paul Buckmaster as the arranger. His mother was from Naples and he could speak Italian. I also like Ennio Morricone, Nino Rota, Dalida and I even like a song by Sophia Loren, Che mm’ e’ ‘mparato a ‘fa”.

Some of us born in the Eighties and Nineties – the so-called Millennials – listen to the Beatles and the Stones, Genesis and Atomic Rooster, the Sex Pistols and the Clash, and we have nostalgia for those years we never lived through. For example, I am not ashamed to admit my ignorance, and I surround myself with biographies, textbooks, and vinyls that fill in the missed decades for me. Do you believe that today’s youth can fill the void left by their parents’ generation? In short, is there a future for rock music?

“I have to agree with you that the music today isn’t quite as good as it was in the Seventies until the Nineties. In the new millennium, something really went wrong. Record labels used to treat pop and rock music culture. They supported the arts! Now they have all kinds of financial advisors, systems, analyses charts – and do you know what? They are selling fewer records than ever before. They are strangling the system with ‘business first, music last’. A young David Bowie or Marc Bolan would never get signed – even a Radiohead-type group wouldn’t get signed.

On a happier note, I will never give up for the future. Many, many young people love my generation’s music and if they persevere then great music will flourish again. I’ve just produced two albums, one with Perry Farrell and the other with Damon Albarn. The quality of their music is just as good as anything made in those golden years. I think both albums will seem like a breath of fresh air”.