On Wednesday April 25th the American Director of the Holy See Press Office, Greg Burke, announced that on July 7 Pope Francis will travel to the city of Bari. For one day he will host an ecumenical gathering with the heads of the Christian communities and of other Churches present in the Middle East to pray for peace.

At the time of Burke’s announcement I was on my way to Bari at the invitation of BIFEST, an annual film festival held there every April. Since I don’t have an outlet for articles devoted to cinema, several days earlier I’d asked the festival’s organizers to set up an appointment for a tour of the majestic Romanesque gleaming white marble St. Nicholas Basilica. So Thursday morning I met with erudite Dominican Father Giovanni Distante, the Basilica’s recently-appointed (less than a month before) Prior. Instead of Greg it was he who, bursting with pride and anticipation, gave me the news of Pope Francis’ upcoming third visit to Puglia in five months.

For July’s trip to Bari will follow one to San Giovanni Rotondo in March to pray at the tomb of the much beloved, but also controversial stigmatist, mystic Franciscan Padre Pio (1887-1968), canonized by Pope John Paul II in 2002; and another to the towns of Alessano and Molfetta in April to recall the legacy of former bishop Don Tonino Bello (1935-68), a vocal critic of international conflicts such as the Gulf War. Bello’s beatification cause opened in 2007 and he became titled as a “Servant of God”.

To my question “Why Bari?” the Prior explained that “Bari is Europe’s window on the Middle East thanks to St. Nicholas, who was born on March 15, 270 AD at Patara Lycia in present-day Turkey and thus a Middle Easterner. Therefore the people of Bari and Puglia view the present dramatic situation of our brothers and sisters in the faith with the same eyes as St. Nicholas, who was a bishop and thus a living witness of Christian providence and God’s love which excludes no one.”

St. Nicholas is worshipped in more places in the world than any other saint. Only the Virgin Mary counts more worshippers. He’s venerated by Western Cahtolics, Eastern and Oriental Orthodox, Anglicans, Lutherans, Baptists, and Mehodists. Because of the many miracles attributed to his intercession, he’s known as “Nikolaos the Wonderworker”. He’s also the patron saint of children, coopers, sailors, fishermen, merchants, broadcasters, the falsely accused, repentant thieves, brewers, pharmacists, archers, pawnbrokers, virgins, students, and of the Duchy of Lorraine, Russia, and Greece, as well as of Aberdeen, Galway, Liverpool, Siġġiewi, Amsterdam, Moscow and of course Bari.

Wikipedia tells us that in his youth St. Nicholas “made a pilgrimage to Egypt and Palestine. Shortly after his return he became Bishop of Myra and was later cast into prison during the persecution of Diocletian. He was released after the accession of Constantine and was present at the Council of Nicaea.” He died at Myra on December 6 (one of his feast days), 343 according to the Gregorian Calendar and on December 19th according to the Julian calendar. Both dates are celebrated with great solemnity in Bari as are the dates of the Saint’s translation from Myra to Bari, May 9 for Western Christians and May 22 for the Russian Orthodox.

According to Western Christian tradition, after the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, Myra, a popular place of pilgrimage because of the Saint’s tomb, was overtaken by the Turks, so taking advantage of the confusion, some 62 merchants from Bari seized part of the saint’s remains and brought them for safe-keeping to Bari where they arrived on May 9.

Again Wikipedia reports: “There are numerous variations of this account. In some versions those taking the relics are characterized as thieves or pirates, in others they are said to have taken them in response to a vision wherein Saint Nicholas himself had commanded that his relics be moved in order to preserve them from the impending Muslim conquest.” Another justifying legend is that once the saint passing by Bari on his way to Rome, had chosen Bari, not Myra, as his burial place.

Almost for certain the sailors from Bari collected just half of St. Nicholas’ skeleton. During the First Crusade (1096-99) Venetian sailors collected the rest. Two scientific investigations in 2014 confirmed that the relics in both cities belong to the same skeleton.

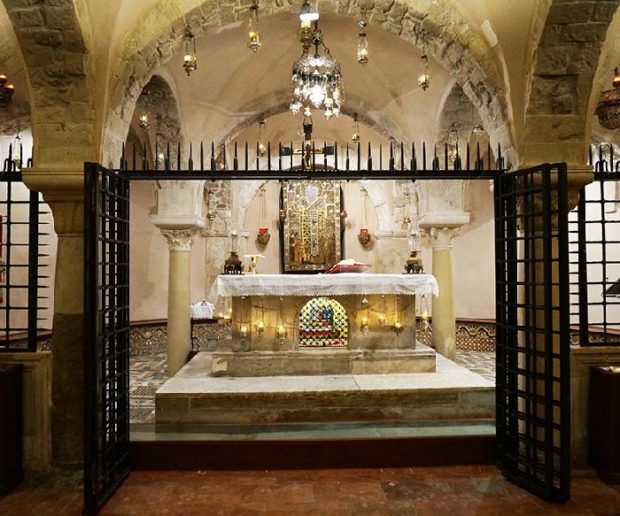

Speaking of relics, after the Russian Orthodox Patriarch Kirill made a specific request to host them during his historic meeting with Pope Francis in Havana, Cuba, in February 2016, Pope Francis lent several of their bone fragments (“from the left rib”, Father Distante told me “because it’s near the saint’s heart”) to Russia last summer in the hopes of building further bridges with the Russian Orthodox Church. Thus, for the first time ever in 930 years they left Bari. After being welcomed by the Patriarch Kirill, they were displayed at the Cathedral of Christ the Savior in Moscow from May 22-July 12, 2017, where they were venerated by over 2 million Russian Orthodox faithful, including Russian President Vladimir Putin. Now it is hoped that the Patriarch will accept the Pope’s invitation to Bari, but at the time of this writing he had not yet confirmed.

It is said that even while still in Myra the saint’s relics each year exuded a clear watery liquid

which smells like rose water, called manna (for myrrh). The faithful believed that it possessed miraculous powers if they were anointed with it. The relics continued to exude manna after they were brought to Bari. Wikipedia tells us that “vials of myrrh from his relics have been taken to his namesake churches all over the world for centuries, and can still be obtained from St. Nicholas Basilica. In fact, even up to the present day, a flask of manna is extracted from the tomb of St. Nicholas every year on December 6 and May 9 by the Dominicans there.

As St. Nicholas is the protector of children and virgins, another ritual celebrated on December 6th is called the rito delle nubili: unmarried women wishing to find a husband can attend an early-morning Mass. In the past they had to go around a column 7 times praying for a husband. Now the column is enclosed in an case of grilled iron for protection so the young ladies place their written prayers inside the case at the column’s base through a hole.

Instead on May 8th the saint’s relics are carried from the crypt of the huge Romanesque cathedral in procession to the port, put on a boat, chosen by draw, which goes out into the sea followed by many other boats. Over 250,000 pilgrims, some 50,000 are Russians, come to Bari every spring to attend this ceremony. The Russians also have their own chapel on the left side of the crypt. In 2007 Putin visited the Basilica and donated a larger-than-life statue of the saint which is in the adjacent square and in 2009 Italy donated The Russian Orthodox Church, which dates to the 20th century and is also dedicated to St. Nicholas, to Russia. It’s located on Via Benedetto Croce 130.

The Basilica of St. Nicholas was built between 1087 and 1197 when the edifice was officially consecrated and Elias, abbot of the nearby monastery of St. Benedict, was named its first archbishop. His Cathedra (bishop’s throne), one of the most noteworthy marble Romanesque sculptures in southern Italy, still stands in the Basilica The choice of the Basilica’s location is similar to that of Czestochowa’s. Instead of horses carrying of the icon of the Madonna to safety refusing to budge, here it was bulls carrying the relics who stopped. Sculptures of their heads adorn the main Romanesque door of the Basilica’s facade. Pope Urban II was present at the consecration of the crypt in 1089.

Besides St. Nicholas tomb in the crypt, that of two remarkable international ladies, mother and daughter, unhappily-married intellectual Isabella of Aragon (1470-1527), who became the Duchess of Bari in 1500 and Bona Sforza (1494-1557), the energetic, ambitious and hot-tempered second wife of Sigismund I the Old, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, who 8 years after her husband’s death returned, like her mother had, to her beloved Bari where she was poisoned, is behind the Basilica’s high altar. It was commissioned by Anna (1525-1596), the 4th of Bona’s six children, Queen of Poland and Duke of Lithuania in her own right.

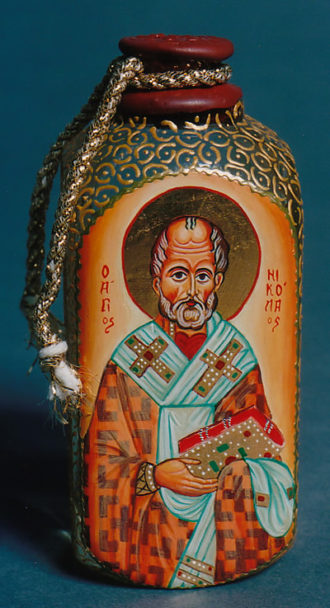

Across from the left side of the Basilica’s apse is the Basilica’s Museum which houses a collection of lamps, chalices, liturgical instruments and vestments, crosses, icons, and votive offerings given by prelates and Russian princes and pilgrims since the mid-19th century. A section of one of the rooms houses Bohemian glass ampullae for manna, many of which are decorated with scenes of St. Nicholas’ life. Downtownon on Via Dottula in the Bishop’s Palace there’s a museum of sacred art.