Research on the interconnectedness of fashion, objects, memory, and technology continues to flow from the Fabric of Cultures project, an interdisciplinary research and pedagogical series supported by Queens College and the CUNY Graduate Center.

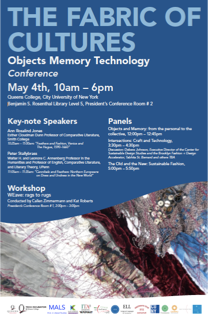

The most recent tranche of analysis was presented at a daylong Fabrics of Culture conference this May that showcased the thinking of academics, students, and experts in fashion, technology, and sustainability. More than 50 participants gathered at the Queens College campus in Flushing, NY to soak up the learning and take part in active dialogue with the presenters.

How it began

The Fabric of Cultures is the brainchild of Eugenia Paulicelli, Professor of Italian, Comparative Literature, and Women’s Studies at Queens College and a founder of the Fashion Studies program at CUNY Graduate Center. The project, now in its second incarnation, originated ten years ago based on Paulicelli’s notion that “clothes matter on account of their materiality, symbolic meanings, and the collective imaginary they engender.” That thought spawned the study of the relationships between textiles and clothing in eastern and western cultures, as well as an exhibition, a scholarly book, conferences, and seminars.

Fabric of Cultures 2.0 takes a fresh look at the evolving cultural sphere of fashion, with an eye to how the physical aspects link to the digital. “From whatever time it comes, the object is never silent or confined to a case in a gallery or museum,” says Paulicelli. “We explore in theory and practice how fibers, fabrics, and clothing, as well as texts, tell and have told the stories of people and communities across cultures, class, gender, race, and space.” One of the ways Paulicelli’s students are pursuing the digitization of their studies is through the Fabric of Cultures website and blog that showcases their work and experiences. The content and findings of the conference in May will be among the components of a multimedia exhibition in fall 2017 at the Queens College Art Center. In the upcoming exhibition, “The Fabric of Cultures: Systems in the Making,” the ongoing Fabric of Cultures project considers the new Made in Italy in a transnational context and in dialogue with other cultures and traditions. The exhibition will be accompanied by workshops and by a Made in Italy Festival: Arts + Cultures and a film festival (Italian Cinema CUNY) to celebrate Italy’s beauty, history, and cultural heritage.

Keynotes on feathers, Venice, and cannibals

The conference’s keynote speakers, Ann Rosalind Jones, Smith College, and Peter Stallybrass, the University of Pennsylvania, engaged the audience with research on an object that might appear to be a frivolous fashion embellishment but in fact carries enormous cultural weight–the feather.

They painted an enlightening picture of how the feathers of specific birds became objects of trade, fashion, fascination, and fashion in the 16th and 17th centuries, including their reference in accounts and renderings of the cannibalistic rituals of indigenous peoples of North and South America who prized feathers for ceremonial and ornamental use. Jones and Stallybrass have written extensively on a broad range of topics and co-wrote Renaissance Clothing and the Materials of Memory, published in 2008.

“Feathers and Fashion, Venice and The Hague, 1590-1660”, the topic of Jones’ presentation, centered on the feathers of the ostrich of Africa and the scarlet ibis of northwest coastal Brazil, including their trade and use in garments throughout Africa, Latin America, and Europe.

These birds and their feathers were “held in awe at their source,” she said. “Associated with the gods of the sky and the spirits of ancestors, birds conferred high status upon the elites entitled to wear their brilliant, light-catching colors–kings, warriors, and shamans–and they were central in religious and social rituals.” Their meanings shifted in “pathways that linked hunters, traders, kings and priests, colonized people, and shippers throughout the Mediterranean and the Atlantic.”

Trade in ostrich feathers was robust in the 16th and 17th centuries and continues to be so today. Trade in scarlet ibis feathers, which were woven into ritual capes or mantles by the Tupinamba tribes, was briefer, but far-reaching. These feathers, Jones said, “were sought after by French traders, Portuguese missionaries, and Dutch colonizers through the 16th and 17th centuries, and some were sent as far north as Germany and England.”

Exotic feathers quickly became fashionable throughout southern and northern Europe: Ostrich plumes adorned military headdress and kings’ capes, the regal women of Venice dressed their hair and themselves with plumes and held fans made of delicate ostrich feathers. The magnificent Tupi mantles painstakingly constructed of scarlet ibis feathers were draped like sashes across the torsos of aristocrats in portraiture.

Stallybrass shifted the focus from feathers as a European fashion choice to an eye-opening analysis of “Cannibals and Feathers: Northern Europeans on Dress and Undress in the New World”. Feather garments figure prominently in the dress of the native people of the New World, he said, as does their “undress” or nakedness, according to accounts by explorers like Amerigo Vespucci, missionaries, and others. Stallybrass argued that the obsession with cannibalism said to have been the focus of Renaissance accounts is exaggerated and is instead “a reflection of 19th and 20th century obsessions with the reality and cultural significance of anthropophagism.” The source, he said, is “over-emphasis on ‘first editions’ and ‘first images’ and by the endless reproduction of these ‘firsts’ that photography and the internet make possible.”

Stallybrass served up examples of how Renaissance explorers and missionaries had in fact “marginalized” cannibalism, giving more prominence, for example, to the importance of feathers. One case in point: Protestant clergyman Jean de Lery’s recounting of his voyage to Brazil in 1556, published in 1578. In the index of a 1594 edition, Stallybrass said “one finds no mention of cannibals or cannibalism. Where one might expect the word to occur, one finds instead “Canide, oyseau de plumage azure.” [‘canide‘, a bird with bright blue feathers.] And if one turns to “plume” or feather, one finds: ‘Feathers used for making garments, headdresses, bracelets and other ornaments of the savages. ‘” Feathers, it seems, trumped cannibalism.

Stallybrass talked about the brilliantly colored ‘canide’, the Tupi name for the blue and yellow macaw, and a coveted object of trade. By the 16th century the bird was kept as a pet throughout Europe and by the 17th century it adorned objects from “German stain glass to English embroidery to Dutch tiles.” The scarlet macaw, also prized for its feathers, was depicted in the earliest maps of the Americas “as the very emblem of this continent.”

He concluded with the observation: “What the feather trade both before and after the Conquest opens up for us is both a more interesting and a more profound approach to the material and social culture of the Americas than the misleading recounting of stories about cannibals and cannibalism–stories that reveal more about us than about early modern European accounts that are more preoccupied with feathers and brazilwood and hammocks and canoes.”

Students, faculty, and industry experts take the floor

The conference shifted to a contemporary view of the ever-changing world of fashion and culture. Queens College and CUNY Graduate Center students and faculty joined by industry experts presented research and observations on the current state of play.

Panel presentations and discussion on “Objects and Memory” featured Fashion Studies graduate students, Chy Sprauve, Iris Finkel, Carolyn Cei , and Cassandra Barnes, giving their viewpoints on the meaning of dress as a means to self-actualization, as a connection to the legacy of loved one, as the personification of cherished objects, and finally as it manifests in the the culture of neighborhoods.

“Intersections: Craft and Technology”, a panel moderated by both Ted Brown, Professor of Computer Science and the director of the Tech Incubator at Queens College and Eugenia Paulicelli, focused on the advances in technology in producing cloth and fashion and how incubator groups are supporting emerging businesses. Debera Johnson, executive director of the Center for Sustainable Design Studies and the Brooklyn Fashion + Design Accelerator was on hand to discuss the mission of her organization. Tabitha St. Bernard, an independent designer of a fashion line without waste and a user of BF+DA services spoke about her innovative solutions. Finally, Elizabeth Wissinger, a professor of Sociology at Borough of Manhattan Community College (BMCC) and the CUNY Graduate Center, presented her views on innovations in wearable technology.

“The Old and the New: Sustainable Fashion” convened graduate students Kat Roberts, Callen Zimmerman, Tessa Maffucci, and Dicky Yangzom, former CUNY Fashion Studies graduate and currently in the PhD program of Sociology at Yale, and Lawrenzo Lue, senior undergraduate student from Queens College, to present their research and views on why reconsidering and repurposing the old makes way for new advances, ranging from fabrics, to the fashion center district in NYC, to an examination of the pros and cons of “fast fashion.” Roberts and Zimmerman also conducted a workshop “WEave: rags to rags” in which participants took part in a collective weaving project to transform jeans into fabric.

Stay tuned for more reports on the fascinating world of the Fabric of Cultures.

Special thanks to Antonino Bonanno for the Italian translation of this article.