When interviewed by Eugenia Paulicelli, in June 2000, fashion designer Fernanda Gattinoni revealed that the advice she had for all her clients was “that they should never copy the dress of this or that actress or celebrity.” According to Gattinoni, a dress should instead match the personality of the individual. While Gattinoni’s words reflect her sincere desire to perceive clothes and accessories as means of creating a unique personality, it is almost impossible to deny the major impact and power that screen stars have had on fashion trends, through their dresses and costumes, from high society to the masses.

It was almost a hundred years ago now that the powerful femininity of the Italian divas fascinated women of all social classes: thanks to the revolutionary art form of cinema, the actresses’ movements, dramatic poses and gestures, while wearing stunning costumes, started to affect the imagination of the spectators and their desire for fashion. How did film and fashion evolve in the course of the 20th century? What impact did fashion in film had on the construction of Italian fashion? How, and when, did the idea of “Made in Italy” develop exactly?

Eugenia Paulicelli’s “Italian Style: Fashion and Film from Early Cinema to the Digital Age,” gives us the answers by shedding new light on the interrelation between cinema and fashion. In her latest work, the author shares her immense knowledge and vast academic research in a clear and sophisticated study that chronologically guides the readers to the discovery of a complex and fascinating world of garments and films. The text offers a deep examination of Italian divas’ strong individuality, and their innovative ways of performing their dress on and off the screen, which led to a first branding of the Italian style; it proceeds with the analysis of fashion and film under fascism, and continues with the exploration of major filmmakers from the fifties on, with a particular focus on Michelangelo Antonioni’s films. Opening with a chapter on Fellini and concluding with a short chapter dedicated to Paolo Sorrentino’s “La grande bellezza,” Rome becomes a central focus of this study, with its pivotal role as a major fashion city after the Second World War. It was only then, in the early 1950’s, that Italian fashion, as we know it today, was born. Paulicelli’s text offers a stimulating journey that painstakingly encompasses the story of Italian cinema and fashion, from its origins to our time.

The first chapter, “Fashion, Film, Modernity” presents an overview of the book, and offers theoretical references that introduce the connections between film, fabric, body, and identity, in the modern world of the early 20th century. Paulicelli refers to Baudelaire’s analysis of fashion, Walter Benjamin’s concern with the relationship between image and copy in the age of mechanical reproduction, as well as to Antonio Gramsci and Peter Wollen on the idea of mechanization of life. The author uses their theoretical approaches to examine, in particular, Massimo Bontempelli’s play “Nostra Dea,” and Pirandello’s first novel “Si gira!” and his short story “La marsina stretta.” Bontempelli’s and Pirandello’s protagonists, Dea and Professor Gori respectively, are seen as emblems of the “structural function” that clothes embody. In Bontempelli’s work, the naked Dea and the dressed Dea respectively symbolize the image and the copy, where the copy is to be intended as the costume, the technology of the body, and her several changes of dress exemplify the multiple perceptions and performances within the social space. In a similar way, Pirandello’s short story reveals the “transformative power” of clothes, and the effects that a dress may have on identity: in this case, the tight frock-coat with its unstitched sleeve causes the unexpected reaction of the professor, and frees him from his habit of conformity to sterile social norms. Paulicelli sees Pirandello’s metaphorical short story as the peak of cinematic discourse in narrative writing, highlighting the strong parallel between the stiches that hold the frock-coat together and the work of montage in cinema.

The book continues with a second chapter dedicated to “Italian Fashion and Film in the 1910s: From the Futurists to Rosa Genoni.” Paulicelli has previously written on fashion and futurism, and has dedicated an entire monographic study to Rosa Genoni. While this chapter echoes some of her previous writings, the analysis of two films serves the author’s objective to investigate the connection between fashion and film. Paulicelli examines “Amor pedestre,” produced in 1914 by Ambrosio Studios and directed by Marcel Fabre, and “Thaïs,” made in 1917 by Novissima Film, and directed by Anton Giulio Bragaglia. The former is not properly a futurist film but, according to the author, clothing takes “center stage,” and the unconventional technique of not revealing the faces of the protagonists, while focusing on their clothes and shoes, certainly inspired the futurists, in particular Marinetti, who staged a similar story in the theater a year later. The second film, “Thaïs,” performs a distinct visual aesthetic through the use of costumes and backgrounds that resemble the abstract art pursued by the futurists. It is fascinating to discover the legacy between some of the first experimental cinematic creations that utilize fashion as a means to stage spectacular performances and futurist art. The section dedicated to Rosa Genoni reiterates important parts of Paulicelli’s study “Rosa Genoni: Fashion Is a Serious Business,” but the pioneer fashion designer is too important to be left out. She is an essential tassel in the puzzle, especially for her understanding of how important it was to create an Italian fashion that could take a stand against the dominance of the Paris fashion houses. Her work planted the first seeds in the realization and conceptualization of a new Italian fashion, and can be considered the female counterpart of the futurists’ goal to reimagine themselves, their space, and their political bellicose projects.

delle sorelle Fontana

“From the Body of the Diva to the Body of the Nation,” the third chapter, investigates the pivotal role of the divas who performed their dresses. Paulicelli’s analysis of Mario Caserini’s “Ma l’amore mio non muore mai” (1913) and, in particular, Nino Oxilia’s “Rapsodia Satanica” (1915) gives critical force to this third chapter. The author examines Lydia Borelli as Salomè, and Caserini’s use of the mirrors to amplify the sense of performance of the actress. The subsequent analysis of Borelli’s role in “Rapsodia Satanica,” then, unfolds a critical discourse that stresses the powerful use of the veil that, as Paulicelli states, “acts as a mise en abyme of the will to live beyond imprisonment of one’s own body and moral constraints,” and examines the color effects achieved with the stenciling technique of pochoir that link “the cinematic and the sartorial.” The chapter continues with Oxilia’s innovative cinematographic technique utilized in “Sangue Bleu” (1914), featuring another diva, Francesca Bertini. Paulicelli defines Bertini’s costumes as a showcase of fashion, and strengthens this argument by showing how cinema and divas dictated the fashion at the time.

The fourth chapter, “Fashion, Film, Modernity, under Fascism” delves into the important aesthetic innovations and experimentation of both cinema and fashion during the fascist regime. Paulicelli demonstrates how the general tendency to perceive fashion and cinema as the main weapons used by the regime for political propaganda is too simplistic. Cinema and fashion were undeniably used as vehicles to construct a new glorious image of the Italian nation, as the desire to fascistize the country was a totalizing project aimed at permeating Italians’ everyday life. Reels and films, indeed, were utilized to stage fashion and make it appealing, in an attempt to advertise a new national fashion; they were educational tools to teach, for example, how to walk and parade properly. However, despite the governmental exploitation of fashion and cinema to consolidate the regime’s power, Paulicelli reveals the complex experimentation that characterizes the reels and films of the time. In her analysis of Alessandro Blasetti’s “Contessa di Parma” (1937), Paulicelli argues that Blasetti’s film is one of the best at emphasizing and publicizing the clothes, a true fashion show that plays an important role in the development of the film’s plot, and embodies, at the same time, tradition, nationalism, and modernity. Mario Camerini’s “Grandi magazzini” (1939) is, then, another significant film that stages Milan, already one of the most prominent cities as far as fashion was concerned, and mirrors the social dynamics and the developing phases of a new modern city during fascism.

“Italian Style” dedicates an entire chapter to Michelangelo Antonioni. According to Paulicelli, “no Italian film director more than Antonioni has had such a knowledge of, and sensibility for, fashion.” “Launching Italian Style in Cinema and Fashion: The Films of Michelangelo Antonioni,” then, begins from the analysis of “Sette Canne, un vestito” (1949), one of the director’s first documentaries, moves to the films that Antonioni directed in the 1950s (“Cronaca di un amore,” “La signora senza camelie,” and “Le amiche”) and 1960’s (in particular “L’avventura,” “L’eclisse,” “La notte”; though the chapter also touches on “Il deserto rosso,” “Blow-up,” “The Passenger,” and “Zabriskie Point”). It was in the early 1950s that Italian fashion was born; in 1951, to be precise, thanks to cinema and fashion shows, Italian fashion started to be acclaimed internationally, and became crucial in the economic reconstruction of the country. Italy, Paulicelli explains, was being finally recognized as a “concrete geopolitical entity” that produced its own fashion, and Antonioni was able to capture the central role that fashion and costumes played in the rebirth of the nation. The author critically guides the readers through the fascinating world of Antonioni’s cinema, examining characters, dresses, fashion shows, and revealing the director’s unique way of using clothes. In Antonioni’s films, Paulicelli argues convincingly, clothes are not simply employed to visually unveil his characters’ roles and their unresolved search for identity; instead, the clothes also respond to the director’s desire to achieve a new aesthetic composition.

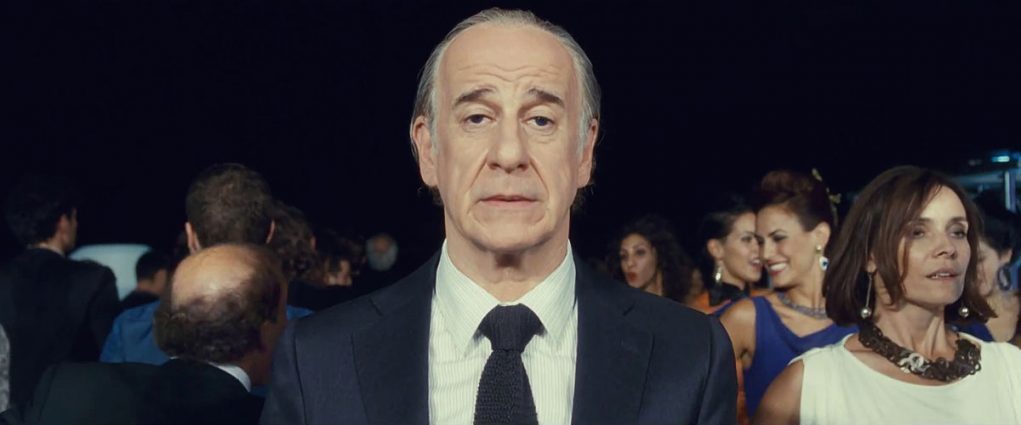

Rome, as the main city where fashion and film intersect, becomes central in the last two chapters of the book: “Rome, Fashion, Film” and “After ‘La dolce vita’: ‘La grande bellezza’ (2013) by Paolo Sorrentino.” Paulicelli examines in a very clear and detailed way the connection between Italy and the United States, “the hybridization” of the two cultures, and the way in which fashion developed its bond with film and the “Eternal City,” a bond that still exists today. The author draws on ideas developed by Francesco Casetti, Roland Barthes, Robert Gordon, and David Harvey, among others, to theorize the notion of experience, space, and the connection of fashion, film, and the city. But this connection, in the postwar, was sparked by very concrete events: the Marshall Plan, which gave the U.S. new control over Italy, the “invasion” of Cinecittà by the Hollywood studios, and last, but not least, the wedding of director Tyrone Power and actress Linda Christian, a media phenomenon that sanctioned the success of the Fontana sisters and Italian style. Rome became the capital of fashion because Rome had Cinecittà, film studios that other Italian cities did not have. Beside fashion, costume design acquired a new importance, and Roman fashion houses became more and more actively involved with the production of clothes and costumes for the American stars, consolidating the relationship between fashion, cinema, and the city, whose complexity is perfectly captured in “La Dolce Vita.” Paulicelli’s reading of Fellini’s “La Dolce Vita” (1960) and “Roma” (1972) adds new insights to the many essays that have been written on Fellini, especially the section that tries to understand what the city of Rome meant, cinematically speaking, to the Italian director. Particularly captivating, then, is the part dedicated to the ecclesiastical fashion show, and the theoretical approach of seeing past and present, reality and illusion, in “Roma.” Sorrentino’s “La grande bellezza” is analyzed in the last chapter that concludes the part dedicated to Rome. Paulicelli scrutinizes, once again, the importance that fashion acquires in the film, and reflects on similarities and differences between Sorrentino and Fellini.

The text is also enriched with photographs from Roberto Palmas’ archive (more can be found on Eugenia Paulicelli’s website), illustrations, sketches, and invaluable interviews with famous fashion designers that immensely contributed, and still contribute, to the industry of fashion and film, such as Fernanda Gattinoni, Dino Trappetti, Teresa Allegri, and Massimo Attolini.

Eugenia Paulicelli’s “Italian Style: Fashion and Film from Early Cinema to the Digital Age,” is a lucid and beautifully written text that promotes, with the qualitative value of its intellectual research, the engaging fields of fashion and film. This text is a must to understand their complex interrelation and influence on the construction of Italian national and cultural identity from the early 20th century to our 21st century.