Born in the Tuscan hill town of Vinci on April 15, 1472, the oldest illegitimate son of a promiscuous wealthy notary and a peasant, Leonardo was a polymath. His interests included invention, painting, sculpting, architecture, science, music (performing and composing), mathematics, engineering, literature, anatomy, geology, astronomy, botany, writing, history and cartography.

According to Wikipedia, “many historians and scholars regard Leonardo as the prime exemplar of the ‘Universal Genius’ or ‘Renaissance Man,’ an individual of ‘unquenchable curiosity’ and ‘feverish inventive imagination.’ Art historian Helen Gardener confirmed that the scope and depth of his interests were without precedent in recorded history, and ‘his mind and personality seem to us superhuman, while the man himself mysterious and remote.”

Of all his talents, Leonardo was and still is renowned primarily as a painter. His two most famous works are the enigmatic portrait “Mona Lisa,” today in the Louvre, and his fresco of “The Last Supper” in the Church of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, which is the most reproduced religious painting of all time. Not to overlook his drawing “The Vitruvian Man,” which is also regarded as a cultural icon and, like the “Mona Lisa,” reproduced on everything from T-shirts to the 1-euro coin.

Over the years Leonardo worked in Florence, Bologna, Cesena, Venice and Rome before King Francis I lured him to France where he died in 1519. He lived in Rome for only three years, from Sept. 1513 to 1516, and he spent most of his time in the Belvedere of the Vatican. So, when “The Leonardo da Vinci Experience” opened at Via della Conciliazione 19 in mid-February, I was surprised to discover that there were two other permanent “museums” devoted to Leonardo here in Rome. One, “Leonardo da Vinci: il genio e le invenzioni” (Leonardo Da Vinci: The Genius and the Inventions), is housed in the earliest Renaissance palace in Rome, the Cancelleria. Once the Papal Chancellery and still Vatican property, it’s off Corso Vittorio Emanuele II. The other, Museo Leonardo da Vinci (The Leonardo da Vinci Museum), is in the Church Santa Maria del Popolo in Piazza del Popolo. This Head Augustinian Church is home to works by Raphael, Bernini, Caravaggio and Pinturicchio. Besides being a pilgrimage site for the Knights Templar, this church also marks the site of the Holy Inquisition and, according to legend, hosts Emperor Nero’s tomb. I’ve put the word museum in quotation marks because neither of these “museums” house original works by Leonardo. In all fairness, neither does their new competitor, The Leonardo da Vinci Experience, except that its paintings are exact reproductions of 23 of Leonardo’s paintings using the exact same chemically recreated paints and old wood panels like their originals, when not canvasses.

I visited all three “museums,” first the newest and then the other two for comparison. The six rooms of the new “Experience,” near the Vatican, cover “The Last Supper,” if sketchily, and Leonardo’s flying machines: among them the anemoscope, glider and parachute; his armaments: the armored car, fragmenting bomb, multi-barreled cannon, self-supporting safety bridge and spoon-shaped catapult; his optical and musical inventions: the perspectograph, double flute; his mechanical achievements: the life buoy, dredging machine, odometer, lifting jack and bicycle; and his paintings. Each one of these objects, scaled in size, some of which have never been reproduced before, is explained in Italian, French, English, Spanish and German, and includes the codex with Leonardo’s description and drawings cited, since he left no models of his inventions, and all of them are hands-on for the delight of children.

“The painting section,” Leonardo La Rosa, the General Manager, told me, “is a work-in-progress. We still have to finish the audio-guide, but it’s already possible to compare the replicas of his two versions of “The Madonna of the Rocks,” one in the Louvre, the other in London’s National Gallery, and of “The Madonna of the Yarnwinder,” one in Edinburgh, the other in a private collection in New York.”

When I asked La Rosa what the point is of a third Leonardo “Museum” in Rome, he explained that 2016 was the 500th anniversary of Leonardo’s leaving Rome for a quiet retirement in France and that 2019 would be the 500th anniversary of his death.

Opened in 2009, “Leonardo da Vinci: il genio e le invenzioni” presents 51 full-scale machines, built by a group of academics and skilled craftsmen in Florence after an in-depth study of Leonardo’s codices. Models of the oil press, the carillon, the hygrometer, the giant crossbow, the prototype for the machine gun, plus a man wearing the life buoy and webbed gloves are displayed only here. Out of choice, there are no paintings except a hologram explaining “The Last Supper,” “Mona Lisa” and “The Lady with the Ermine,” which was reportedly added later. Pluses include excellent explanations in Italian, English, French, Spanish and German, wheelchair accessibility, an elevator and restrooms.

Grande Exhibitions’ permanent Leonardo da Vinci Museum in Santa Maria del Popolo opened in 2010. Like its new competitor, it has six underground rooms divided by category with hands-on exhibits. However, it offers many more models, an assault ladder, a covered cart for attacking fortifications, a proto-type of scuba diving equipment, a hydraulic saw, a portable piano, for example, and an all-inclusive audio-guide in Italian, English, French, Portuguese and Spanish. Moreover, its wall panels in Italian and English have much more detailed explanations and display additional categories of Leonardo’s codices, a model of his ideal city, his anatomical drawings and his fresco of “The Battle of Anghiari” for Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio, as well as videos about Leonardo the sculptor and about his “Last Supper.” These videos included some details I’d never heard before: for example, that his famous fresco was the earliest work-of-art with the apostles showing emotion and with Judas sitting at the table with them, instead of alone. The Museum’s main weaknesses are its faded photographs of Leonardo’s paintings showing just their titles, but no explanations and there are no bathrooms or accessibilities for the disabled.

But, let’s return to Leonardo and Rome, where he came at the behest of Giuliano de Medici, Pope Leo X’s brother and commander of the papal troops. Sparknotes reports that, during his three-year stay there, Leonardo “pursued architecture, hydraulics and the dynamics of mirrors. Moreover, at this time the Medici empire’s fortune depended largely on the dye industry and Leonardo attempted to fashion a parabolic solar reflector that would speed the boiling process essential to the making of dyes.”

Artistically speaking, in Rome, Leonardo drew his well-known self-portrait as an old man. This drawing is remarkable because it was drawn from an angle and not head-on, which implies that Leonardo had probably arranged a complex system of mirrors to draw himself from this angle. In addition, he completed his last major painting, “Saint John the Baptist,” now in the Louvre. Today, only one or maybe two of his paintings are in the Eternal City.

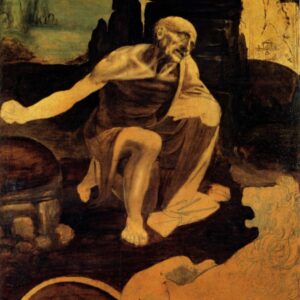

Dating back to c. 1480, Leonardo’s “St. Jerome in the Wildnerness,” was not painted in Rome and was left unfinished. It is now at the Vatican Museums, and probably remained in the artist’s possession until his death. According to the Vatican Museums’ website, it was first mentioned and attributed to Leonardo in the painter Angelica Kauffmann’s will (1741-1807). “On Kauffmann’s death, all traces of the painting disappeared, until it was found by chance and purchased by Napoleon’s uncle, the Cardinal Joseph Fesch. According to legend, the cardinal discovered the painting divided into two parts: the lower part in the shop of a Roman second-hand dealer where it formed the cover of a box. The top part, with the head of the saint, was at the shop of his shoe-maker who had used it to make the cover of his stool. Regardless of the story, the painting can actually be seen to be cut into five parts. On the death of the cardinal, the picture was auctioned and sold a number of times until it was identified and purchased by Pius IX (pontiff from 1846 to 1878) for the Vatican Pinoteca (1856).”

Another painting in Rome has recently been attributed to Leonardo. It’s “The Adoration of the Christ Child” in the Borghese Gallery, previously attributed to Fra Bartolomeo. After a recent cleaning, the Borghese Gallery sought attribution as a work of Leonardo’s youth based on the presence of a fingerprint similar to one that appears on “The Lady with the Ermine,” now in Krakow. The results of the Gallery’s investigation are not yet published.

On until April 17th in Rome’s Musei Capitolini (Capitoline Museums), there is a temporary exhibition about Leonardo’s “Codex on the Flight of Birds.” In this handwritten, from right to left, 18-page notebook on loan from the Royal Library in Turin, Leonardo wrote and illustrated his studies on the flight of many species of birds along with wind resistance and currents. It’s likely that page 10v features a hidden self-portrait.