In 1927 Alfred Barr, the first director of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and one of the most influential figures in the development of modern art history, travelled to the Soviet Union, where he met prominent members of the Russian avant-garde. Barr described Russia as one of the most important artistic centers of the late 1920s, and after his two-month stay he included Suprematism and Constructivism in his revolutionary survey of modern art at Wellesley College.

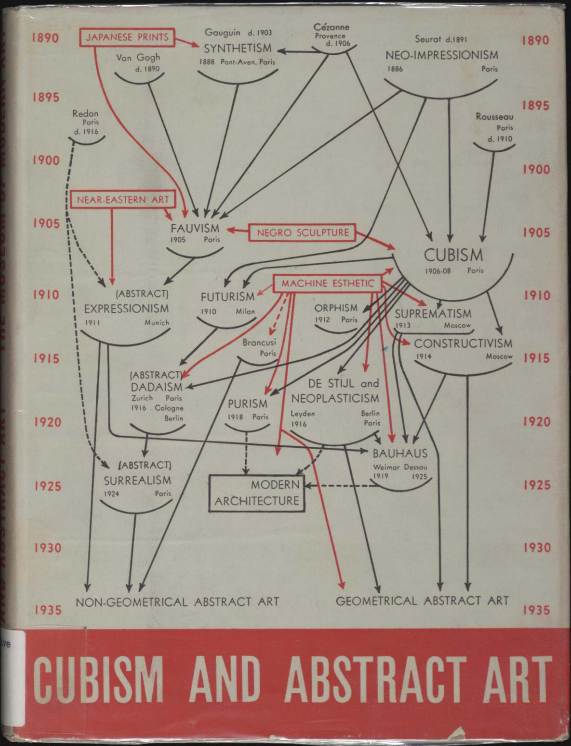

This experience had a significant impact on him and influenced his view of what MoMA could be: a place of art and discussion. Furthermore, Barr facilitated the transmission of works from Russia to the MoMA, and in the 1936 exhibition “Cubism and Abstract Art” he established the works of the Russian avant-garde as paramount to the evolution of abstraction. The narrative of this 1936 exhibit continues to shape not only the Museum’s presentation of modernism, but also the canon of European modernism today. Thus MoMA’s current exhibition, “A Revolutionary Impulse: The Rise of the Russian Avant-Garde,” which draws from the museum’s extensive permanent collection of Soviet works ranging from 1912 until 1935, can be seen as an expansion on Barr’s vision of the Russian avant-garde and its place in art history.

Staged in anticipation of the centennial of the Russian Revolution (October 1917), the exhibition brings together a range of artworks in a variety of media to address the question: how can an object be revolutionary? In early twentieth-century Russia, artistic innovation and political turmoil were at times indistinguishable. By the time Vladimir Lenin’s Bolshevik party overthrew the tsarist autocracy of Russia in 1917, many artists had already been working towards revolutionizing academic conventions by creating art based on Marxist principles. In some instances their aim was to make a universal art of the people, which led to the creation of abstract paintings and constructions. In other cases artists sought to propagate visions of a utopic future state by incorporating innovative forms of design, architecture, theater and film. Both forms illustrate the intimate ties between artistic and political revolution. Moreover, the objects displayed in “A Revolutionary Impulse” bring to the forefront the socio-political agency of artists during times of instability.

The exhibition begins in the hallway with a series of prints from 1916 by Olga Rozanova entitled War. Opening the exhibition with the work of a female artist signals the dominant role women have in the Russian avant-garde. In the Soviet Union of the early twentieth century, there was an association between commodity culture and the subjugation of women. The objectification of women was a symptom of capitalism and was therefore viewed as antithetical to the revolutionary impulse of the Russian avant-garde. “A Revolutionary Impulse” reflects this mentality by omitting the female nude and sexualized depictions of women from the exhibition—not that there are many to be found in these movements to begin with. Furthermore, works by artists like Lyubov Popova and Natalia Goncharova feature prominently, highlighting the centrality of women artists to these movements.

Movement, artist, and media roughly divide the galleries. The first series of rooms are devoted to the movements of Suprematism and Constructivism. Featuring such noteworthy works as Kazimir Malevich’s “Suprematist Composition: White on White” (1918), Aleksandr Rodchenko’s “Spatial Construction no. 12” (1920), and works from El Lissitsky’s “PROUNseries”, these rooms provide a range of materials including paintings, prints, drawings, constructions and manifestos.

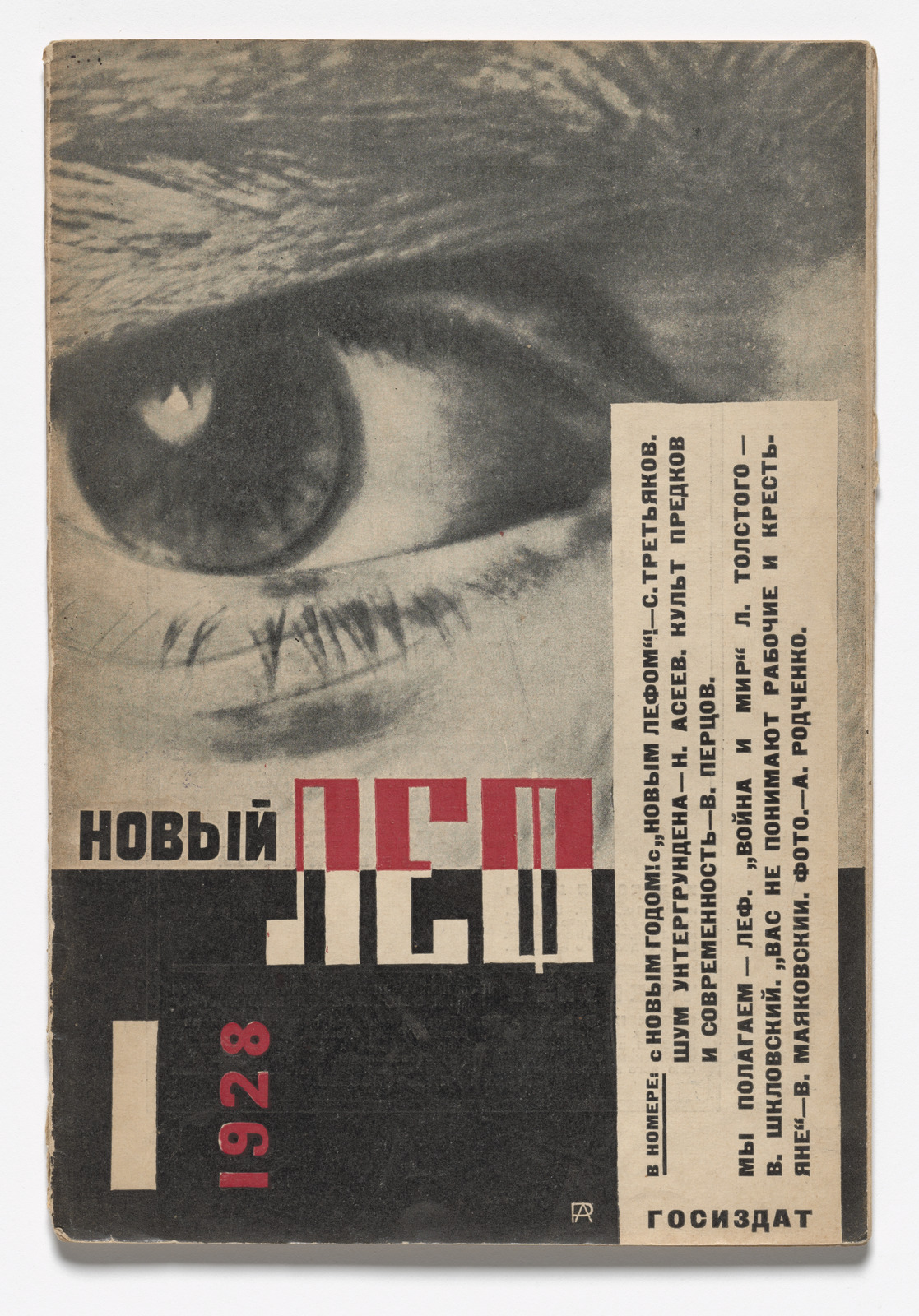

The use of a wide range of media continues into the next few rooms with explorations in theater, film, and photography. The show includes such iconic works as El Lissitzky’s photomontage “Self-Portrait” (know as “The Constructor”), 1924. Some works are even featured several times in different modes and media. The silent documentary film, “Man with a Movie Camer”a (1929), directed by Dziga Vertov, for example, can be found in three different forms. It runs as a movie clip; it is advertised a movie poster designed by Vladimir and Georgii Stenberg; and it appears as a still of the film in a New LEF journal designed by Rodchenko. This repetitive inclusion of the same work in multiple forms speaks to the multiplicity of objects in the Russian avant-garde. Many works were realized more than once in varying media.

The remaining gallery looks to the later developments of artists working in the late 1920s and early 1930s under a government headed by Joseph Stalin. As the government placed new restrictions on all aspects of life, the artworks in the last room reflect a focus primarily on the production of propaganda, including books, posters, magazines, architectural drawings, and models. Remarkably, some decorative artworks that are rarely incorporated into exhibitions of the Russian avant-garde are displayed, including Nikolai Suetin’s teacup set of 1923 and Rodchenko’s enamel pins for the state airline of Dorolet from 1924-25.

Although the curatorial statement notes the dominance of Socialist Realism as the official art of the state in the 1930s, the patriotic paintings charged with transforming the nation’s inhabitants into Soviet citizens are markedly absent from this exhibition. Constructivism and the other abstract movements associated with the Russian avant-garde and the Red Revolution did not die organically, but were actively snuffed out by the government.