Fifteen years ago, without any idea about the place his work would be exhibited, painter and artist Archie Rand began transforming each of the 613 Jewish mitzvahs, or commandments, into its own breathtaking painting, a series that took five years to complete.

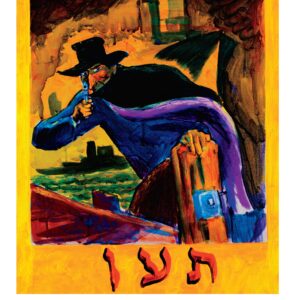

In 2008, Rand mounted an exhibition of The 613 in a Brooklyn warehouse; the paintings covered 1700 square feet of wall space andthe public viewing lasted only four hours on a single day, but more than one thousand people attended. The New York Times featured the exhibition and described The 613 as “a rendered in the style of comics and Pulp Fiction book jackets, a dash of Mad Magazine, a spoonful of Tales of the Crypt, some grotesque, some superheroes, always action, emotion, drama”. Now, in his new book The 613 (Blue Rider Press), Rand collects all of these panels ̶ beautiful, shocking, insightful, funny and transgressive ̶ into a single book, with one painting per page accompanied by the commandment in text.

Rand lives in Brooklyn with his wife Maria Rand Catalano. Formerly the Chair of the Department of Visual Arts at Columbia University, he is currently the Presidential Professor of Art at Brooklyn College CUNY. He tells La VOCE about his book and his art.

As you said, “Judaism and art don’t mix well”. But you have created a new Jewish iconography. Is there any political, religious message that you want to express with your work?

“For many years Judaism was an iconoclastic religion although it wasn’t always so. The 1932 discovery of the murals in the Dura-Europas Synagogue in Syria proved that there had been a vibrant tradition of figurative, narrative painting in Judaism existing at the same time that the Talmud was being written. As Jews became increasingly nomadic, painting was, for many reasons, gradually eradicated, weakly using the second commandment as justification. So, making art came to be seen as a “non-Jewish” activity and Jews who were involved in art as practitioners, critics or salespersons did so with the knowledge that they were engaging in an assimilative, anti-observant, activity. In the 18th and 19th century factions of Judaism broke off into the Haskalah movement, which encouraged Jews to adopt the more agreeable secular customs and cultures of their host countries. Some Jewish artists began to re-surface, supplying a product for those recently emerging Jews those who had maintained their identification but did not subscribe to an exclusionary Orthodoxy. In the early 20th century, Bernard Berenson, born Jewish in Lithuania, established the notion that wealthy people could obtain the highest pedigree of sophistication if they purchased “old master” paintings, which he would then authenticate. The persuasive logic was that these acquisitions would guarantee that the owner’s position, in the center of high society, was unassailable. These paintings would then act as talismans and possessing them would guard the collector against any regression back into the proletariat, from where the newly monied classes had come. The 20th century produced a great amount of art dealers, collectors, and art historians who were Jewish and a surprisingly large number of Jewish artists.

The Jewish artists, with the notable exception of Marc Chagall, used their freedom to enter into artmaking. Most made accommodation with the simultaneous appearance of modern art, which allowed more abstract ways of portraying the world and therefore did not contradict the second commandment while not compelling these artists to make any overt narrative reference to their own Jewish experience.Places of Jewish ritual and studying casually adopted the installation of stained glass windows, in architectural and social deference to their Christian neighbors, as the glass’s transparency revoked the tangibility of the portrayed objects. But wall paintings or paintings in general, because of the specificity of their articulation, would still be considered scandalous.

In 1974 my work was brought before a religious court for heresy. In question were murals that I had done in an Orthodox Synagogue. The paintings were acquitted. The highest rabbinic authority declared that painting was permitted even under the strictest interpretation of Jewish law. In my subsequent paintings I continued to construct original iconography based on illustrating whatever scenes in Scripture or clerical commentary contained a description of an object or situation or an action.

The general rabbinate is not eager to enforce this court’s verdict, which insures the Jewish artists’ legitimacy. If paintings were freely allowed in Judaism, the unrestricted license for the viewer’s imagination, to make subjective assumptions from paintings, would seriously undercut the influence of any clerical interpretations of the same passages in the text. Judaism encourages the debating of contradictions and revels in the subtle resolutions that, still, may remain open to question. In Christianity, which is more hierarchical, paintings nurture faith, through the meditation and introspection that art can produce. As the Church’s doctrine is relatively inflexible there is no fear of paintings causing apostasy because there is constancy in the teachings.

Also, a more delicate historical problem is that painting a wall with identifying symbolism is a permanent structural modification, like tattooing a building. Paintings are unlike any other art form in that they are not time-based. A painting sits on a wall, twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, broadcasting, naming the values of the inhabitants of a space. All paintings do this. All paintings….

If painting in Judaism had been encouraged, through the centuries, the visual announcement that, say, a fresco would make would declare that this space would be eternally prevented from being eradicated as a Jewish space because it relentlessly transmits identity. It’s paintings invite discourse with illusions and allusions that have sole, Jewish, ownership. This would cause discomfort among all people who have tacitly agreed that the Jews be understood, from within and without, as a diasporic culture. This realization brings implications that have major religious and political significance.

So my creating a “catch –up” iconography, even an artificial, arbitrary iconography – an iconography purporting to align itself with each of the mostly obscure and unheeded Jewish “commandments”, is an act of refurbishment to manifest a visual language, which has been historically and awkwardly amputated from Jewish culture. Some see this as a radical act and I see it as a natural and necessary addition to a universal visual culture, from which Jewish reference has been eliminated by an understandably complicit arrangement. It just seems to me that the world’s cultural coordinates have currently docked in a peculiar trajectory where the universal and Jewish visual necessities are in a position that would accommodate the passage of Jewish personality past the global aesthetic membrane and into the larger dialogue.”

Which is the feedback from Jewish community about The 613 book?

“When The 613 was shown as a painting there was some dissention, at the exhibition, from some wings of the Orthodox community. However immediately after that showing I received enthusiastic and encouraging responses from rabbis who were members of the exact same sect of Orthodox practice that had seemed discouraging a few days previous.

Jews in America are as atomized as have become other migrant cultures because the freedoms allowed by the American lifestyle foster a community’s dissolution into the whole. However I have found that The 613 is attractive to all segments of Judaism, both in this country and on other continents (remarkably, it has become a best-seller). Especially as a gift ̶ as most Jewish books are scholarly and appeal to a niche audience.

The 613 is seen as “fun” and is given to adults and children alike. A large portion of its sales has been to people who are not Jewish but who like the pictures or the anomaly of the pictures ill-fittingly residing next to a Biblical text. Some of the more observant Jewish people, and Christians and Muslims as well, have commented to me that it is an enjoyable way of getting adolescents to become familiar with an otherwise dry Biblical subject. Among youngsters, in the ritually observant Jewish community, I frequently hear that they love the pictures and enjoy flipping through the book, as this is an easy introduction to an imperative subject ̶ because The 613 is a topic of required study among the Orthodox.”

You said that the comic book style inspired you in your panels. Is there any other artistic language you got inspiration from?

“Many of the American comic artists of the 40’s and 50’s and early 60’s were Jewish so that was a style I  could adopt while paying homage to an undervalued cultural property. Working in series inspired some of my earliest paintings, a group of paintings with musicians’ names sequentially inscribed on them, which I did from 1967 to 1971. At that time I had been looking at Egyptian hieroglyphics and Chinese characters, where “word-pictures” succeeded each other to form a language.

could adopt while paying homage to an undervalued cultural property. Working in series inspired some of my earliest paintings, a group of paintings with musicians’ names sequentially inscribed on them, which I did from 1967 to 1971. At that time I had been looking at Egyptian hieroglyphics and Chinese characters, where “word-pictures” succeeded each other to form a language.

I grew up with the long playing 33 rpm record, which allowed me to hear musicians play for more that the 3 minutes that was previously available on 78 (or 45) rpm records. So people like (saxophonist) Sonny Rollins could play many, many choruses of one composition, going on for fifteen minutes or more. Therefore the idea of the extended solo seemed culturally natural to me. James Brown could repeat a vocal but rhythmic phrase without conceding the necessity of a primary melody as do the composers Steve Reich and Philip Glass. In my introduction to the book The 613 I mention my debt to the ceaseless poetry of John Ashbery and the continuous, almost interminable, unpredictability of Cecil Taylor’s music. The serial art of the minimalist artists like Sol Lewitt and Andy Warhol’s work influenced me and although, at the time, I didn’t feel emotionally attached to the work I was impressed by  the idea of repetition as having narrative value in itself. On Karawa’s use of words in his “date” paintings and Ed Ruscha’s use of seemingly irrelevant words against pictures made poetry for me. The Torah scroll itself, in Judaism, is read in an automatically re-starting cycle of chapters, which imparts a Jewish familiarity with the idea of a structure built on contiguous continuance.

the idea of repetition as having narrative value in itself. On Karawa’s use of words in his “date” paintings and Ed Ruscha’s use of seemingly irrelevant words against pictures made poetry for me. The Torah scroll itself, in Judaism, is read in an automatically re-starting cycle of chapters, which imparts a Jewish familiarity with the idea of a structure built on contiguous continuance.

In The 613 I had visions of making a wall that emitted a sacredness without resorting to a false piety. The majestic revelry of the Buddhist cave paintings at Ajanta and the paradoxical grandeur and intimacy of the Brancacci Chapel or Piero’s work in Arezzo were foremost in my mind although there is a blatancy, a declaration, that seems to approach, out from the walls, at Dura Europas, which I wanted to emulate. All of the examples noted above contain a balance of raucous electricity and a monotone solemnity: two sides of existence.”

What mostly drew your attention in creating these panels: the secularization of “Jewish Art” or the visual aspect?

“Since I was creating an “instant” iconography I wanted to use images that were immediately digestible. So the visual was always paramount. I understood that this was going to be a process that would secularize Jewish art so I had to leave the implied demand, of respecting the inviolate by dutifully illustrating the text, on the side of the road.”

Archie Rand will be at Brooklyn Museum on March 12 for a reading.