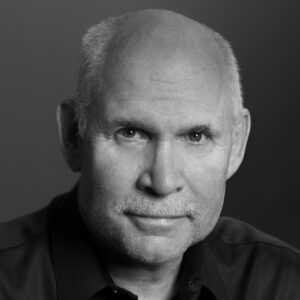

Despite an ongoing pandemic, made of isolation, incredible stillness and missing hugs, we are now able to travel (and dream) again thanks to the American photographer Steve McCurry and his new book In Search of Elsewhere. The author of the famous portrait of the ‘Afghan girl’ – whose striking green eyes remain to this day among the most iconic and well-known of the 20th century- and the undisputed master not only of street and portrait photography but also of war reporting, gifted us with this book at a time when the need to escape has never been greater.

Despite an ongoing pandemic, made of isolation, incredible stillness and missing hugs, we are now able to travel (and dream) again thanks to the American photographer Steve McCurry and his new book In Search of Elsewhere. The author of the famous portrait of the ‘Afghan girl’ – whose striking green eyes remain to this day among the most iconic and well-known of the 20th century- and the undisputed master not only of street and portrait photography but also of war reporting, gifted us with this book at a time when the need to escape has never been greater.

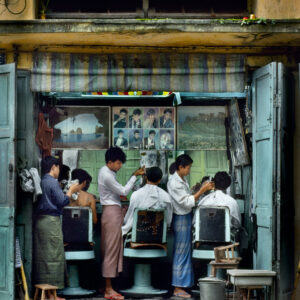

In this collection of previously unseen images, pulled from the archives of over 40 years of work, we gradually dust off our sense of adventure as we let ourselves be transported around the world, from India to Myanmar, to the United States, passing through Italy, and between different periods, like in a real time capsule. McCurry looks at the world with incredibly loving and compassionate eyes, like a father would at his children, and through his lens we rediscover our shared humanity. The message of the book is clear: in spite of all our cultural and generational differences, we share more than what we think, as COVID-19 brutally reminded us. Forced to stay at home, in Pennsylvania, like everyone else, the wandering photographer doesn’t hide his frustration, but also his happiness at spending time with his young daughter and at finally having a routine, for once in his life.

How did you get the idea for your newly released book, In Search of Elsewhere?

“It was mostly while going over old material that I hadn’t looked at for some time, like 10 or 20 years, and looking at it maybe in a different way. With time and distance, you start to see things differently, with more of a historical perspective. I wanted to go back and revisit my archives, something that I was already partly doing because we’ve been scanning a lot of pictures lately.”

What are you trying to convey with this book?

“The book is kind of a poem. It’s about my journey and my wanderings through various parts of the world, and about the things that I cared about, things I thought needed to be documented and remembered. You know, life is short and we need to have a memory of how we were, how the world was. This book documents my travels over the past forty years, but more importantly, it records the ways in which people live out their everyday lives, no matter the joys and the difficulties.”

Revisiting a photo archive can be very daunting. Is it something you enjoyed doing nonetheless? Is it as fulfilling as capturing those moments?

“Yes, you kind of relive some of these experiences and that’s fascinating, to be able to look back and remember that particular place, event or person, thinking ‘I can’t believe I was there’. I also see how I photographed and saw things compared to now.”

Have you noticed more continuity or evolution in the way you photograph today?

“A little bit of evolution. Now, with digital photography, you are able to photograph in much lower light and therefore, photograph things which would have been impossible to capture 20 or 30 years ago.”

Speaking of things that are difficult to capture, you said that several pictures in this book would be very difficult to reproduce today because some places are less or no longer accessible today. Can you give an example?

“There are parts of Yemen that are now inaccessible, and also parts of Afghanistan that are ‘no-go zones’ today. I think that the life there has changed dramatically.”

While looking back at some of your photos of Tibet from 30 years ago, you’ve noticed that people have since changed the way they dress, that some of their traditions have faded or disappeared today. In your opinion, is it inevitable for a culture to evolve and sometimes lose its specificities or should we prevent this from happening?

“I don’t think that we should prevent cultures from evolving. I think that Italy made a conscious decision to preserve their past. Some countries choose not to do that. First of all, we do not want to deny anybody education and health care; progress is inevitable, progress is unstoppable. I do think that some cultural traditions need to be preserved. Music, food, architecture, the way we dress, these are some of the things that make a culture unique, and regional differences are nice. But inevitably we all want – or just start – to dress the same. It’s just a fact, there is nothing you can do about it.”

When traveling around the world, is there something you learned and ‘picked up’ from other cultures?

“Respecting other people, being polite and being kind, and the importance of family, these are all things I’ve seen in many cultures and that I practice daily.”

Have you ever had any cultural clashes?

“Sometimes in Afghanistan people can misunderstand what you are doing and you have to explain to them the purpose of what you are trying to accomplish. For example, men there usually don’t want ‘their’ women photographed. I usually don’t try to convince them and move on.”

What is your creative process as a photographer?

“It’s about what moves you and what inspires you, it’s all part of the creative process. For me it’s about walking down the street: you’re alive, you’re trying to appreciate the world, your life, where you are and what you are seeing. And then you respond to certain things around you, things that you think are important, that you find revealing or that illuminate a situation or a place, or something that you want to remember, that you want to communicate. You just photograph from your heart, from your gut. You need to photograph what you believe in, what fascinates you…it’s the only way you can work, from your heart.”

There are several pictures from this book that were taken in Italy. What is your relationship with this country?

“I visited Italy for the first time in 1970. Italy is so full of Art. Italians care about Art, beauty and style, and they care about their past. That’s why we all love Italy so much. Some countries, they tear everything down to build steel structures, for example. But there is a charm, a beauty and an elegance to that particular Italian ability of preserving what is part of their (and our) past. That’s why people want to spend time there.”

It seems that you have been to Italy quite often since the 70s, is that correct?

“Well yes, maybe one or two…hundred times!” (laughs)

You talk about Elliott Erwitt like a model that young photographers should discover, praising his wit, humor and curiosity. Is curiosity important to you?

“I think we are all curious. Some people are more curious than others. The difference with me is that, in addition to being curious, I photograph the things I am curious about – or the places, the people, the situations. People are fascinated with different things. I happen to have a fascination with human behavior, other cultures and travel. I think you can make a particular comment or interpretation of a place or a situation with photography. Elliott is a keen observer and sees the world in a particular way and that’s wonderful, to have people with these unique points of view.”

What about your point of view?

“What interests me is what you see in my pictures. Human behaviors, telling a great human story. It’s photographing the world and trying to show the commonality of humanity. Since we are here for such a short amount of time, the most important thing for me is to see the world and what it holds, its treasures, beauty and wonders.”

Talking about curiosity, how can we stay curious in a world where we often feel numbed by the volume of information directed at us?

“I think you have to be selective on how you spend your time. Try to avoid being bombarded with a lot of nonsense, avoid being caught up in all the noise, and actually concentrate on the things that have value and are important to you.”

Going through your archives, it is inevitable to think about the passing of time. Do you personally feel pressured by time? How do you approach the process of aging?

“I think we all feel the same pressure. Time passes, we age and we are all destined to die at some point. This is life, there is literally nothing you can do about it (laughing). All you have to do is accept it and I guess try not to obsess over it. Because whether you accept it or not, time marches on!”

Photography has the ability to actually stop time and capture a particular moment. Is this why you like this medium, compared to others?

“Yes. It’s a way to stop time, to create and keep a visual memory, otherwise things just disappear, that particular moment is lost forever. Without a photograph of your mother or father, there will be no memory of how they were at that particular time, you won’t be able to see it and go back to it. Photography is a way to have that memory. To me, it’s like being able to see something that impressed me, that I thought made a comment about life, and saying ‘this had value to me and I wanted to preserve this memory’. I also think that what we all love about photography is being able to see how we looked like when we were children, while going through the family albums – something I like to do now and then.”

Talking about the past, is this what your new book represents, a sort of time capsule of our world?

“Yes, it’s a little bit about the way we were, the things that have happened, that I witnessed and that were important to me.”

You studied cinematography and in that degree program you were also required to study theatre, acting and set design, along with still photography. Did that help you in your work later on?

“I don’t think that theatre arts specifically helped me in my photographic career, but you never know how you might be influenced by a literature class, or a history class, or a geology class…I think all knowledge is useful. Education is important for everybody, in any place of the world, at any point in time. Education is essential. That’s the only way we’re going to survive as a planet.”

You said that “photography is more effortless and spontaneous than filmmaking” and that’s why you prefer it. Would you ever direct a movie today or do you still have no interest in making films? Are there any movies that particularly shaped you in your youth?

“I would be happy to direct a film. Some of the films that have inspired me are Stanley Kubrick’s Paths of Glory, Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times, and David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia.”

When mentioning the photographer Roy DeCarava, you once said that “only a black photographer could truthfully interpret the lives of African Americans”. Do you think that a photographer can truthfully depict someone only if she/he has gone through the same experiences?

“I think that in terms of photographing the ‘black experience’, someone like DeCarava or Gordon Parks have a lot more insights than I ever will. I could still try to capture ‘it’, in my own way, but their photos will always have more depth.”

You have been capturing people who are very different from you, in terms of background and culture. How did you manage to have that same level of depth in your photos?

“I think that all you can do is photograph them – we are all humans, we are fundamentally the same, and I think you always enter a situation with your own background, and therefore you photograph them in your own way. Maybe I don’t understand the culture the way they do, but I can certainly have my own point of view.”

Talking about a special photograph by Robert Capa – one where a family of refugees is pushing a covered wagon carrying their possessions – you said that Capa clearly had deep empathy for that family. Do you also feel empathy with your subjects? If yes, does it usually help you or prevent you from capturing them?

“I do believe that a good portrait photographer needs to have a sense of compassion and empathy for his or her subjects.”

Throughout your career, you have been an active participant in what you were capturing, rather than a distant observer. In one interview you said that “the only way to tell the story of a flooding is to get in the water like everybody else. But if you’re timid and hold back, it’s not going to happen”. Is this also how you approach life?

“I think that we all tend to be shy, and unless you are willing to put yourself out there, you are not going to get what you want. Going up to strangers, getting up at four o’clock in the morning or trying to get access to certain things, life is about struggle and fortitude and perseverance. If you just sort of casually approach things you might not have the same result as someone who is actually making a serious effort. Anybody who is trying to accomplish something, whether he/she is a scientist, an architect or an athlete, needs to be really serious about it.”

Would you say you are no longer shy today?

“I may be shy, but I’m willing to try to overcome it. You don’t necessarily get over it, you just have to deal and work with it.”

When talking about your work, you always mention ‘serendipity’, comparing photography to ‘a blank page’ in which the element of surprise and the unscripted are the best parts. How much do you rely on serendipity in your life?

“There are certain things you need to plan, and other things you can leave to chance. For example, you can wake up one morning and plan to go somewhere, but then leave up to chance what you will do once you get there. I think that fun lies in the discovery. If things are too planned, it might not be as joyful or satisfying.”

Was there a time when a ‘serendipitous moment’ happened but you were not prepared to capture it and missed an important shot?

“There are always missed opportunities. There are missed opportunities every day, there is failure every day.”

How do you cope with failure when it happens?

“You just have to move on. In life there are failures and disappointments every day, for everyone. You just have to be positive because there are literally no alternatives, unless you want to be a very sad, negative and grouchy person. But that’s not fun. Not for you, not for anybody! That’s actually a recipe for disaster. So, you have to get over it and move forward.”

Your career was built on taking (and sometimes making) one opportunity after another, and often by taking risks, like when you bought a one-way ticket to India. How do you decide which risks are worth taking and how far you can go for a photo?

“I think it’s on a case-by-case basis. It’s calculating the costs against the benefits, evaluating the risks and the rewards in a daily moment-to-moment decision. Sometimes you do have to take risks. They don’t necessarily have to be life-threatening, but you gotta take risks, like we said before, you cannot be timid. You can’t say ‘if I go to India, I might not make it’, otherwise you might as well just stay home. But there is no right or wrong, it all depends on how you want to spend your time on this planet.”

Speaking of life-threatening risks, you said that you do not consider yourself a war photographer, yet you have covered a lot of war zones and conflicts, how come?

“That was a long time ago. About 25 years ago I’d say!”

So, this is something you moved away from over time?

“Yes. I did it, but there are other things in life that I want to explore, other things in life that I want to experience. I don’t think you have to do the same thing over and over again, that doesn’t sound particularly appealing. You can reinvent yourself. For me, that page, that particular chapter is now closed.”

Travel is an important part of your work because you wanted it to be. Where does this urge to travel come from?

“I’ve always been driven by a need to explore and wander, and photography for me is the perfect companion to that need. I find that the only way to really understand life from someone else’s point of view is to step into their place, both figuratively and literally. There is no substitute for walking with a person in their home to understand what life is really like for these people. Experiencing different cultures is sure to make you more attuned and have greater insight into people and their surroundings. It helps to establish a relationship between yourself and your subject because by experiencing their culture, you are gaining an understanding of a big part of who they are… you’ll find that people really respond to that. There’s no mystery or trick to it, aside from being respectful and open.”

When traveling to dangerous places, you often said that you felt like you were on a mission. What was that mission, and is it the same mission today?

“The most important element in my photography is storytelling. Most of my images are grounded in people. In my portraiture, I look for that unguarded moment and try to convey some part of what it is like to be that person, or in a broader sense, to relate their life to the human experience as a whole.”

Some people may not know that you have a foundation called ImagineAsia. What is it about?

“ImagineAsia helps children in rural Asian communities by addressing fundamental education and healthcare needs. We work in partnership with community leaders and local non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to establish primary schools, which offer the added benefit of medical care. ImagineAsia is dedicated to assisting in the implementation of pilot programs in the fields of peace, education, computer literacy, health education, and environmental awareness. One of our main goals for the immediate future is to provide for a medical clinic and doctor to visit the schools monthly. We are working to bring these programs to other villages in Afghanistan, Tibet, Pakistan, and India.”

Your first destination once this pandemic is over?

“Myanmar and Thailand.”

As reflected in the title of your book, would you define your career as a quest for “elsewhere”?

“The overarching theme of this collection is that no matter how divided our world is, there are more things that bind us together as humans than divide us. There is no denying that the world has changed, but people are still basically the same, even in these times of turmoil, disease, ecological degradation, and economic hardships. So, my search for elsewhere revealed that no matter where I have gone, I have experienced humanity, kindness, hospitality, and generosity, and that has made all of the travel worthwhile.”