Enzo Mari (1932-2020) was the poet of design, who knew how to see justice and truth within objects as a phenomenology of their creation process. The world knows he passed away a few days ago.

The first thing that came to my mind as soon as I heard the news was to think of my mother, a Milanese architect who is a generation younger than Mari and his spiritual student, who used to collect the children’s books that he and his wife created. I thought about how she leafed through them with passion, trying to make me interact with shapes and colors. It occurred to me when I moved out on my own when I was 18 and, since I was a penniless student, I was trying to assemble Ikea furniture or hack fruit boxes and old benches to turn them into chairs; my mother always commented, sniggering: “You should read Enzo Mari’s Self-design manual!”.

In our house Enzo Mari was part of the subtext, of those deep-rooted cultural references that accompany you both consciously and unconsciously. Maybe that’s why, when I told her that Maestro Mari was dead, she exclaimed: “IL NOSTRO (our) Enzo Mari!”.

What’s more, Enzo Mari’s wife, Lea Vergine (1935-2020), an Italian curator and art writer, died the night after, from complications related to COVID at the age of 82. The couple’s passing, which came a few hours apart, as if Lea couldn’t wait to reach her beloved husband and partner, triggered a reaction of grief and pain throughout the intellectual community. “The great Master”, “the legend”, “the rebel” Enzo Mari and “the unconventional”, “the divine”, “the great intellectual” Lea Vergine, left us a huge legacy, and now we have the chance to honor it.

In an interview for Klatmagazine in 2014, Enzo Mari talks about his wife and about his idea of love: “We have been fighting for fifty years. I had a first wife, I had girlfriends. I met Lea by chance, in Naples, after she had asked Giulio Carlo Argan to recommend someone who could take care of the graphics for a magazine. So, I went to Naples, in a hotel, around noon, I didn’t see anyone in the big hall. Suddenly, at the back of the room I saw a man and her, who was then 26 years old. I was standing like an idiot. Lea was a beautiful girl, but I was too shy and thought vaguely mythological about beautiful girls. For me they were a kind of gift from the divinity that came to you from heaven. If God thought you deserved it, He gave you this chance to meet the woman of your life. (…) Love is not like a project, it is much simpler. It is to stand up like a fool, like that, at the back of the room, with her there looking at me, and take two or three steps towards her. And she is taking two or three steps towards me. Maybe love is taking two or three steps in the same direction.”

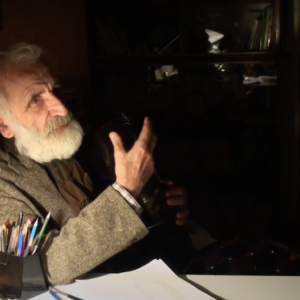

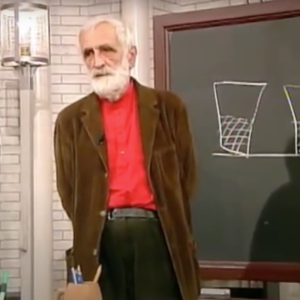

When the world got notice of Enzo Mari’s death, Hans Ulrich Obrist and Francesca Giacomelli had just inaugurated a retrospective of works by Mari at the Triennale Milano, narrating over 60 years of activity, through a series of contributions from international artists and designers who have been invited to pay tribute to Mari with site-specific installations and new commissioned works, and a series of video interviews by Hans Ulrich Obrist that illustrate Mari’s theoretical understanding, and his extraordinary design skills with which he has given shape to the essential.

His vision of design industry shows his constant ethical tension, which oscillates between a strong desire for social justice and a clear picture of history and reality. In these words, his poetry justifies his choices and gives a precise sense to his personal corpus of works: “Italian design was not invented by the designers of Milan, but by the artisans of south Italy who then lost their jobs due to urbanization and the spread of technology. The artisans produced essential items for the peasants: those items were not called design, but it was the result of craftsmanship.”

He identifies the birth of industrial production as an event that occurred to fill the need for equality for free people: “The industry was born in the mid-eighteenth century with a very high percentage of poor people, who started to require ‘shoes and underwear’ when the word égalité has been first pronounced.. The handcrafted object, which was made in Versailles, was simply too expensive. (…) The worker should earn a percentage, even a small one, on the proceeds of his industry. He would no longer collect his salary, but after fifteen years he would become a partner in the company.”

Enzo Mari also had a radical vision of school, an institution where people “are mistaking freedom of expression with ignorant anarchy, to an orchestra whose elements are hopeless at music yet stubbornly refuse the signals of the director because they think they know better, producing pure cacophony, and in which two or three amongst them actually know what they are doing and play really well, but nobody hears them”. His judgment was severe: “I abhor schools. But above all, those teaching specialization: they bring people to think that the Humanities, that are the ethical backbone to everything, are useless in today’s world. Yet the knowledge that they give in exchange is nothing that an intelligent person could not pick up in a few weeks of work (…) real knowledge is hard work. (…) Schools are a business. They exist to shape people to support industrial needs: making things that please the mass and last as little as possible, so they can be replaced. Supporting this means supporting a family thinking, not a societal thinking. (…) I say let’s teach our kids to be craftsmen, to master again the art of drawing (a slow skill that requires thinking), to understand what was done in the past, and why and how.

Mari’s own experience, his childhood in post-war Italy, may have influenced his judgment because he needed to develop a creative thinking about design for survival. Born in the southern region of Puglia in 1932, Mari moved as a child with his family to the north, where they struggled to make ends meet, and he had to rely on his precocious resourcefulness. He believed that children are our uncontaminated genius: “When a child is born, he has billions of neurons connected to each other, and in fact children are very intelligent, I often repeat: you should give the Nobel Prize to a two-year-old”.

What we can learn from Mari is that design has to be “an act of war, not a game”, a practice aimed at creating accessible, useful and democratic tools. “Design is now just perceived as form” he used to say, comparing the leading fair of the sector, the “Salone del Mobile” of Milan, to a vulgar mass-market, in which “designers are totally lost in the mad search for something new that will make people rich and famous” forgetting the mission of creating useful and meaningful objects for everyday people.