At the end of April, about a week after his press conference with Stampa Estera on Facebook, Eike Schmidt, Director of the Uffizi Galleries, announced the purchase of a very rare print: a panoramic view of Renaissance Florence dating to 1601. “The Uffizi”,” he explained, “had recently bought it from an antiquarian map dealer in California.”

An internet search led me to Barry Lawrence Ruderman in La Jolla, who told me that he’d bought it a year or so ago at auction from the Swann Gallery in New York. Apparently, the print had been owned by an elderly lady on Manhattan’s Upper West Side who was unaware of its rarity and value.

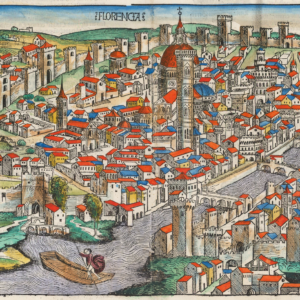

There are two older “panoramic views” of Florence. The oldest one is called “Florence in Chains” because of a padlocked chain illustrated around its frame. Initially incorrectly attributed to the little-known printer Lucantonio degli Uberti from Florence but active in Venice, the xylograph (or woodcut, 58.4 cm. high by 131.5 cm. wide) is now for certain acknowledged to be the work of the peripatetic Florentine artist and cartographer Francesco Rosselli (1445-1513)–also the author of splendid Ptolemaic planispheres—and it dates back to between 1482-90. According to Ruderman’s website www.raremaps.com, there is no surviving original, but it almost certainly was the inspiration for Hartmann Schedel’s view of Florence, published in the Nuremberg Chronicles in 1493.

Although there could be others that I didn’t discover, my research led me to only three copies by Rosselli: one in Berlin’s Kuperstichkabinett (Museum of Prints and Drawings), another in London’s National Gallery, and a third in Florence’s Biblioteca Nazionale, but according to the Uffizi’s Curator of Prints and Drawings, Laura Donati, these copies were printed later. The earliest known to survive is Berlin’s (1510).

Moreover, yes, Rosselli’s is a “panoramic view”, but like Schedel’s, it’s a woodcut and not printed from a copper plate. Nonetheless, a huge 19th-century pictorial reproduction of Rosselli’s “view” is on display in Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio. The three woodcut prints and the painting all show in the lower right-hand corner a portrait of Rosselli on a hill above the Oltrarno drawing his bird’s-eye view of the city below. In the painting the artist is dressed in red.

Instead, again according to Donati, the prototype of the less-condensed Uffizi’s “panoramic view”, thus the third chronologically-speaking, is more refined and detailed than Rosselli’s. It was first engraved and etched in Antwerp by brothers Lucas and Jan Van Doetecum and printed in 1557 by the Flemish painter and etcher Hieronymus Cock (1518-70), the most important print publisher of his time in northern Europe. For between 1548 and his death Cock’s publishing house, Aux Quatre Vents or de Vier Winden (The Four Winds), a partnership with his wife Volcxken Diercx, published more than 1,000 prints. La Voce di New York’s readers might also be interested to know that, according to Ruderman’s website, Cock, whose father Jan Wellens and brother Matthys were both painters and draftsmen, had lived in Rome from 1546 to 1547. Not to mention that the historian of architecture Vincenzo Scamozzi, from Vicenza, had copied many of the engravings of Rome published by Cock in 1551 for his volume on Rome, Discorsi sopra l’Antichità di Roma (Venice, Ziletti, 1583).

Now to return to Florence, the Uffizi’s press release stated that the only surviving copy of Cock’s 1557 print Florentia, had once belonged to Leo Olschki (1861-1940), the highly esteemed rare book dealer and publisher of scholarly tomes in Florence. He was said to have sold it to the National Library of Sweden in the late 1930s, but only after it had been displayed in an exhibition in the Accademia in Florence in 1935. It was this fact in particular that aroused my curiosity about the Uffizi’s latest purchase. I had had the privilege of knowing one of Olschki’s grandsons, Bernard “Barnie” Rosenthal (1920-2017), also a highly esteemed rare book dealer first in New York City and later in Berkeley, California.

I therefore contacted the Kungliga Biblioteket (Sweden’s National Library) for more information about its print’s provenance. To my disappointment the curators answered that they were unaware of the Olschki connection. Rather, they confirmed that the 1557 print had once belonged to the Swedish statesman Count Magnus Gabriel de la Gardie (1622-86) and had been in the National (formerly Royal) Library since 1780.

Instead, the Uffizi’s print dates to 1601, because, in 1600 when Cock’s widow died, the famous engraver Phillipe Galle, once Cock’s associate and then executor of Diercx’s will, retained many of Cock’s copper engraving plates but soon sold some of them, including Florentia, to another Dutch engraver, Paul van der Houve, who’d settled in Paris. Hence, Van der Houve “edited” the plate and the Uffizi’s unique view (printed on three sheets of paper for a total size of 36 centimeters high by 130 centimeters wide) is dated Paris, 1601. Otherwise it’s the same as Sweden’s, hence the view is the same and it dates to 1557. Visible are its medieval city walls (demolished by the architect Giuseppe Poggi in 1865), Giotto’s bell tower, the Duomo (Cathedral), Palazzo Vecchio, Palazzo Pitti, Santa Maria Novella and Santa Croce. Missing is the Uffizi building because in 1557 Cosimo I de’ Medici had not yet commissioned Vasari to build it and the Boboli Gardens are still just farmland.