LEGGI QUESTO ARTICOLO IN ITALIANO

In the few months since opening in January 2016, GR Gallery has accustomed us to grand rediscoveries. After the inaugural group show and the exhibition dedicated to Alberto Biasi, from now until July 17 it’s the solo exhibit of Franco Costalonga with Revolution.

Venetian Franco Costalonga is now 83 years old and began as a self-taught painter in the Fifties, and later joined the Dialettica delle Tendenze group and later the group Sette-Veneto, linked to Bruno Munari’s Sincron. He is one of those artisan artists that has an expressive form and a vocation in his art, a know-how that is based in Italian artisan tradition. Fascinated by Russian Constructivism, Costalonga over time conducted rigorous research that intersected the science, math and the physics of light and color.

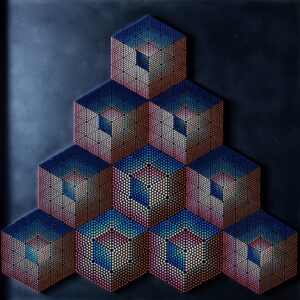

On view at the GR Gallery are thirty of his works from the early ’70s to 2015. The exhibition, the first of this artist on American soil, focuses on the artist’s most kinetic works featuring works from the series Oggetti Cromocinetici Rotanti, Oggetti Quadro, Riflex, Mokubi e Onde Gravitazionali.

Eva Zanardi, the gallery’s manager and art advisor, does not hide her passion for this artist. She enthusiastically shows me each of the works on display, inviting me to observe the details and most importantly to interact with them. “This is an exhibit that must be seen live, that must be lived – she tells me – Seeing photos of these works doesn’t work, because a photograph can only capture one perspective, whereas the perspective of these pieces changes depending on the viewpoint. Kinetic art is triggered by the observer and these works are sublime examples of this.” Indeed, you can’t stand still in front of these compositions: their colors, lights and shapes transform before your very eyes. Each piece is many different pieces, each composition contains many more, which have been studied and calculated with mathematical precision to appear to move as the spectator moves.

“Also because of his love of Constructivism, Costalonga has always strived to create art that is reproducible and because of this he has always worked with modules. Moreover he too, like Constructivism, is very interested in materials: the material is not at the service of the art but an object itself within the art with which to experiment.” In some works, for example Mokubi or Oggetto Quadro Rotante, the kinetic effect comes from the way in which a series of minuscule wood cylinders are assembled and colored to create texture and form. Initially Costalonga created these small individual cylinders by hand then he started to use wooden cylinder modules that he patented and reproduced. The effect is incredible. The piece seems to move and some compositions, like the very beautiful Clindretti ruotante, has an organic character: the combination of form and color gives life to the material, making it fluid, almost soft, despite the geometry of its forms.

The artist’s patents are also found in his most recognized works, spherical mirrored caps from the Oggetto Cromocinetico series. Here too it is the play of movement of the spectator that produces variations of depth, color and design in the half spheres. The result is so modern that it’s hard to believe that the first of the pieces in this series dates back to 1970.

In some of these works the movement is a direct result of the perspective of the spectator and a series of optical illusions. Other pieces actually do move, as is the case for example of Oggetto Quadro Ruotante, 1975. Thirty-six modules are assembled in 6 rows of 6 that rotate because of 36 small electric motors, each at a different speed, creating infinite combinations. There is then an instant in the rotation, Eva Zanardi reveals to me, when all the yellow lines in the inner part of the artwork align: “It is perfection that originates in chaos. But it’s only for a second because perfection doesn’t exist so chaos returns.” I was not fortunate enough to see it and it is not predictable as to when this perfect alignment repeats itself: it is the mysterious allure of science, but I would have gladly stayed to observe those points and lines chasing each other endlessly.

Equally as hypnotic are Costalonga’s most recent works, Riflex, which were inspired by the concept of gravitational waves and play on multicolor light patterns based in information technology, and demonstrate that his 83 years of age do not deter him from neither experimentation nor the technologies available today, as an artist who has always been interested in light.

His appreciation of Einstein’s research has inspired Costalonga to apply scientific precision in his objects of art, but it’s not only an exercise in design: “He has always upheld that art is for the people, it must be accessible to the masses, overcoming that elitist perception that is generally associate with the art world – explains Eva Zanardi – in fact when Penny Guggenheim wanted to purchase his art for her museum in Venice, the story goes that the gallerist called him and asked him his price. Costalonga, who because of his ideological convictions was not fond of the Guggenheims, said he would not give her not even the slightest discount. Apparently Peggy then commented: Costalonga, my foot! His last name should be Costacaro (costs a fortune).”

The political view, together with the artisan precision with which we’ve already become familiar in the works of Biasi, are qualities that are common to Italian kinetic art artists which is specialty of the GR Gallery. The gallery is a New York derivative of the Studio d’arte GR of Cacile, in the northeastern region of Friuli Venezia Giulia, originator of the recently rediscovery of Kinetic Italian Art, the market value of which, from 2000 to 2010, increased by 128 percent, but that still needs to establish authority on this side of the Atlantic. “The main difference between Italian Kinetic Art (which we in Italy call Arte programmata) and American Kinetic Art – explains the gallery manager who works for the specific purpose of introducing these artists to America – is the strong political message of the movement in Europe, especially in Italy. It’s based in the Russian Constructivism credo that kinetic theoretician in Italy, Bruno Munari (who set a new auction record on June 14, 2016 with Macchina Inutile, 1945, selling for 152,000 euro) reevaluated in the early Fifties with his Manifesto del Macchinismo. Munari had a profound critical vision of the art market that he maintained was elitist, and the commerce of artwork. The solution was to create art that was reproducible in a series and by multiplying it a low cost, their price would collapse. America trivialized Kinetic art, making it a pop phenomenon (especially from 1965 on with the MoMA exhibit The Responsive Eye that renamed kinetic art Op art). Moreover, at that time American Pop art was catching on everywhere. Unlike Kinetic and programmed art, Pop art didn’t promote any criticism to the art system – on the contrary, it would exploit it until it conquered the entire art world; Pop art could be seen as anti-programmed art. As Costalonga says: American Pop art killed Kinetic art.”

The exhibition is a veritable amusement park where you need to make time to come into contact with each of the pieces displayed. In an era dominated by the digital, finding yourself in front of still objects that suddenly animate themselves thanks to simple mechanisms of visual perception, has a certain magic to it: a sensorial experience that is priceless.

LEGGI QUESTO ARTICOLO IN ITALIANO

Translation by: Enza Antenos